Doctors could soon prescribe screen time for children with ADHD.

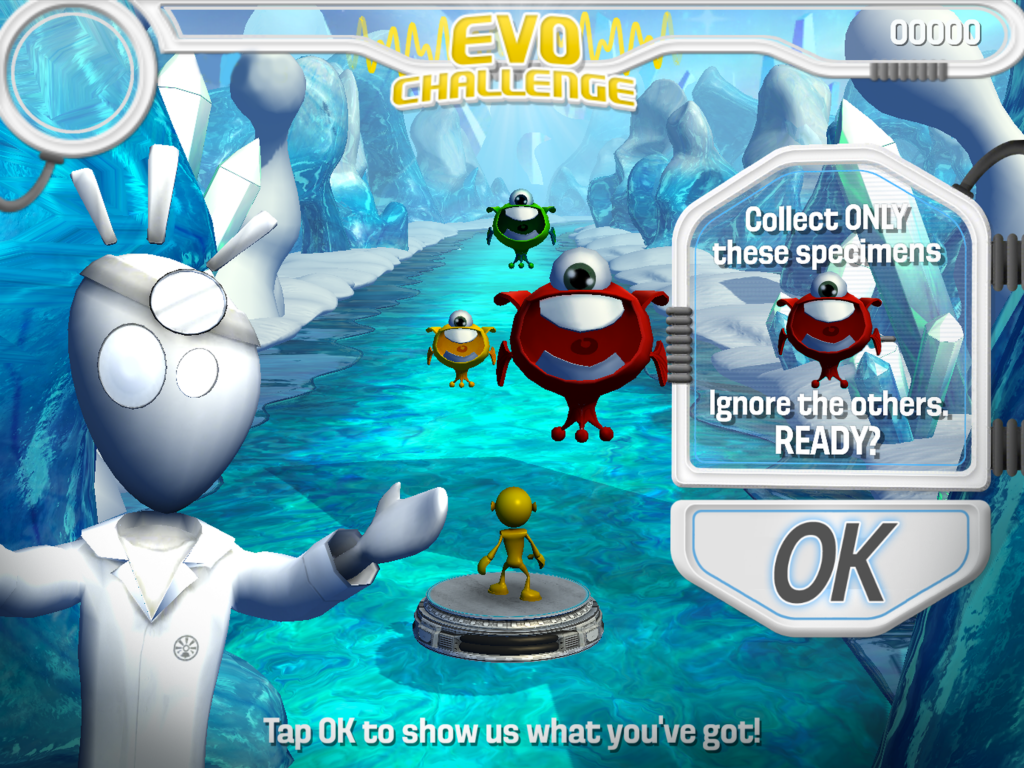

In the video game Project: EVO, you navigate roiling river rapids while dodging rapidly shifting obstacles and connecting with friendly flying characters. To earn stars and advance to the next level, you have to demonstrate multitasking mastery. Unlike other games that reward these kinds of skills, in this one you must prove to the game’s algorithm that you have made a leap in neurological function.

This is no ordinary entertainment — it’s a video game designed to lessen the symptoms of ADHD. And one day soon, it may be available by prescription and reimbursed by your insurance company.

The creator of Project: EVO, a Boston-based tech company called Akili Interactive, is betting that video games, often blamed for exacerbating behavioral and mental conditions, could actually provide successful treatments for ADHD. And it won’t just be kids playing on doctors’ orders. People on the autism spectrum, seniors with Alzheimer’s, and patients recovering from brain injuries may also benefit from playing games targeted to their specific neurological deficiencies.

Akili is working with the University of California, San Francisco’s Neuroscape Lab to build on the success of a game called Neuroracer, developed by UCSF neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley, which was shown to be a powerful tool for cognitive enhancement in adults aged 60 to 85.

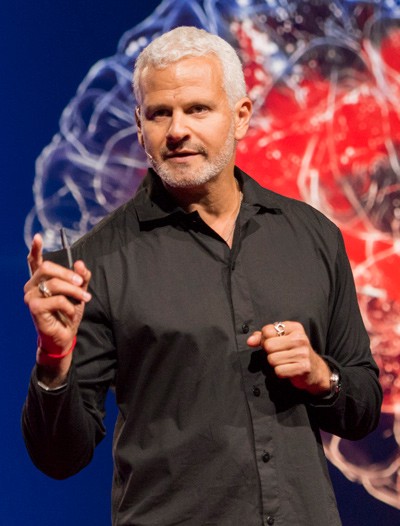

In a 2013 study featured on the cover of Nature, Neuroracer’s multitasking features were shown to lead to improvements in real-life tasks that required working memory and sustained attention. In that game, players steer a virtual car while carrying out other actions that challenge their executive functioning. After 12 hours of this training, seniors were able to consistently beat 20-year-old novice players. The results were so astonishing that Gazzaley, a strikingly fit and even-keeled 40-something, became a darling of the Silicon Valley self-optimization set, a sort of med-tech celebrity who regularly speaks at tech conferences and dazzles the media with his plain-spoken charisma.

Over the past 12 years, Gazzaley and his team have collaborated with designers and artists to develop a range of video games that might be able to treat a wide range of brain disorders. Now with investment backing from PureTech Health, an R&D and venture creation firm, Gazzaley and the Akili team are charging into unknown terrain: securing approval from the Food and Drug Administration for a video game.

It’s a slow, deliberate process that’s at odds with the shoot-first way tech is usually developed. The FDA requires any kind of drug or medical device to go through multiple phases of large-scale, randomized, double-blind clinical trials that must all succeed. There are hundreds, if not thousands, of legal and procedural details that must be airtight, so Akili has 11 full-time employees working in its compliance department. Now in the final Phase 3 trial, the Project: EVO game is close to becoming the first prescription-based video game.

If it gets approved, the implications are big. Prescription video games could become an enormous market even though they face the perception that screen time is generally not beneficial. And they could give children with ADHD an intriguing alternative to the stimulants that are prescribed for them with astonishing regularity.

Safeguards

Matt Omernick heads up product development for Akili, and was recruited by Gazzaley while he was executive art director at LucasArts. Omernick says the rigorous FDA approval process will assure medical professionals that the game is beneficial. “Get to market fast is not the strategy, and our investors know that,” he says. “Hopefully we will be the first to define a very new industry — digital medicine.”

Aside from a company called Posit Science, which is in talks with the FDA about using video games to treat various cognitive disorders, competition is virtually non-existent. However, persuading doctors and regulators is a steep uphill climb because several companies, including Lumosity and Neurocore — which counts Education Secretary Betsy DeVos as chief investor — have come under attack for making false claims about their benefits. Gazzaley himself has been among the critics.

The very idea of using video games therapeutically goes against the “you’ll rot your brain” conventional wisdom that is in fact validated by numerous studies. While some research has shown that playing video games consistently can lead to significant improvements in vision and attentiveness, even more studies demonstrate the negative effects of screen time, including serious addiction — particularly for those with ADHD, attention problems, and anti-social tendencies.

It’s a slow, deliberate process that’s at odds with the shoot-first way tech is usually developed.

Omernick says that Project: EVO has built-in safeguards to ensure that it’s only used for one 30-minute session per day, so kids can’t get addicted to it. It stops functioning entirely after the daily session. He stays away from the swirl of controversy surrounding kids and screen time by taking a very pragmatic approach: “No matter what, video games are not going away, and this is one that is actually beneficial for your brain,” he says.

Kids who are prescribed the game will go through behavioral and neurological assessments first. Then, they’ll play the game on an iPad for half an hour a day, five days a week, for four weeks. The game is entertaining and visually immersive, offering up the kind of rewards that kids are familiar with from other video games. At the start of the training, a cartoon character in a lab coat explains the session’s objectives. Players learn to position and tilt the tablet to control an avatar traveling through outdoor environments while hitting targets and avoiding distractors. Even for me, a neurotypical 39-year-old, the game is fun, challenging, and hard to put down.

Unlike an over-the-counter game, in which all players have to do the same things to advance to higher levels or earn rewards, Project: EVO is a completely individualized tool for each player. It measures neurological skills such as perceptual discrimination, visuomotor tracking, and multitasking ability, says Omernick, and players move on only “once you demonstrate that you’ve actually changed something neurologically. So the game pushes you to improve a part of your brain, like a personal trainer.”

After the four weeks of gaming, the players are once again thoroughly assessed for attention, processing speed, and reaction times. The clinical team asks parents to report kids’ symptoms, observes how the children behave during the month, and interviews the kids themselves about how they are feeling and how they believe they might have progressed. The Project: EVO pilot study results released last April showed significant improvement in attention abilities for all participants, and sustained effects for up to nine months.

Other possibilities

The Akili team is also setting up similar studies with autism spectrum disorder, depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and traumatic brain injury. Last December, Akili announced promising results in a study of a digital screening platform that detects biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. The device, called AD Screen, is also in late-stage clinical trials.

But unlike with ADHD, this space is a bit more well-traveled. Posit Science has offered a cognitive enhancement game, BrainHQ, for five years. The Southern California branch of AAA offers older drivers a chance to complete 10 hours of training in the game in exchange for a discount on their auto insurance, says Posit Science CEO Henry Mahncke; he believes that health insurance discounts for patients who complete brain training will soon follow. Some of the exercises in BrainHQ, when combined with other treatments, have been shown to reduce the risk for dementia and even to help people with early Alzheimer’s.

Gazzaley says that most of the Akili games in development offer preventive potential as well, possibly protecting kids from developing ADHD, or lessening cognitive decline in adults. In fact, he maintains that the games could enhance cognitive abilities in everyone. The Neuroscape team is now working with school systems in the San Francisco Bay Area to train students to perform better academically using its video games.

But it’s not yet clear what the overall experience would be like for people who just pick up the game on their own, without a prescription for a certain condition. Among the details that haven’t been nailed down: Would non-prescription users have access to Akili’s clinical team as well? Would it be prohibitively expensive?

Cutting back on meds

It’s clear that parents and medical professionals are looking for an alternative way to treat ADHD. Diagnoses of hyperactivity disorder have skyrocketed in the past decade, affecting an estimated 11 percent of kids ages 4–17. About half of these kids take powerful drugs to lessen their symptoms and make them more amenable to classroom learning, following rules, and staying still.

Prescriptions of Adderall, Ritalin, and related drugs are up 28 percent since 2007. These drugs often present side effects, ranging from loss of appetite and weight to cardiac irregularities and slowed growth. They’re also widely used illegally off-label for their stimulant effects among the college set. It’s not yet fully understood how these drugs affect the developing brain, making each child a walking experiment. Adding to this, concern is growing that the ADHD diagnosis — which has criteria that are subjectively determined by clinicians — is incorrect about a third of the time, leading millions of kids to take drugs that they don’t really need. So Project: EVO offers a completely new framework for helping ADHD kids.

The idea that a video game could replace or reduce pharmaceutical treatments makes more sense when you consider that social, rather than behavioral and neurodevelopmental factors, frequently influence diagnosis. It’s the youngest kids in a classroom cohort who are more likely to be labeled hyperactive. Black and brown kids are diagnosed more often than their white classmates. To put it in historical perspective, hyperactivity wasn’t even acknowledged before compulsory schooling began in the 19th century. In many respects, children have become the target of modification because — let’s face it — fundamentally changing the social and environmental structures that negatively influence their behavior is more than a bit daunting. It’s widely acknowledged that in less rigid environments, children appear to evidence ADHD symptoms much less.

It’s clear that parents and medical professionals are looking for an alternative way to treat ADHD.

Emory University physician and anthropologist Mel Konner has proposed that ADHD is a matter of what’s known as evolutionary mismatch. The trait of short attention may have once provided survival advantages, but in the modern context it has become maladaptive because our environment is so different from the context in which Homo sapiens evolved, and our genes haven’t caught up. “These kids have hunter-gatherer brains in the modern context,” he says. “The testing regime in schools, coupled with the cutbacks in outdoor recess and art programs means that we are making the mismatch worse.”

Some solid research has found that kids with ADHD show significant improvement after getting regular outdoor play in natural settings, essentially recreating the hunter-gatherer lifestyle in small doses. And adventure sports disproportionately attract people who can successfully channel their ADHD energies into mountain climbing or paragliding. Similarly, Posit Science CEO Mahncke says that cognitive decline in seniors could be caused by lifestyle factors. Most people in the developed world are now sedentary, and our professional lives involve becoming narrowly focused on one type of task, in one place. Even if that task is intellectually demanding, that intensity is not what keeps our brains sharp. “Humans are one of the most adaptable animals — we can live anywhere — and what sustains us and maintains our brain health is constant new learning and adapting to environments,” Mahncke says.

But health professionals find it hard to write a prescription for an environment or a lifestyle. Take the idea of outdoor play — how much is effective? What kind of play is best? Are some spaces more beneficial than others? And what about the majority of people who don’t have easy access to wilderness?

That’s why Gazzaley thinks a video game prescription will likely be the most reliable treatment alternative for ADHD — and eventually for other disorders. “With almost 100% of newly diagnosed cases of ADHD, parents are asking: ‘Is there anything else I can do for my child besides drugs?’” Gazzaley says. “Our goal is to be on the pharmacy shelf next to Adderall. Any doctor will have the ability to prescribe our video game, which has a delivery system that is better than any drug.”

This story was updated on September 25, 2017, to clarify differences between the cognitive improvements associated with the version of BrainHQ that is available now and the possible improvements that studies have documented in an experimental version of the game.