In a new book, Emily Peters explores the perspectives and solutions artists, designers, and musicians bring to our broken health care system.

The new book Artists Remaking Medicine is a look at how art practices both old and new can be harnessed to tip the scales in favor of more positive outcomes and better experiences for everyone involved in the U.S. health care system, from doctors to patients to family members. Health system designers and managers should take note: this book injects some powerful, elegant, and inclusive ideas into a debate that often feels like it’s going nowhere.

Created by Emily Peters, a self-proclaimed “health care raconteur” whose work as the founder and CEO of Bay-area branding studio Uncommon Bold centers on helping guide brand strategy for health care clients, Artists Remaking Medicine is the second book from her own imprint, Procedure Press, after Women Remaking Medicine, which was published in 2019.

The book is full of gorgeous images, typography, and design, and includes contributions from artists, designers, doctors, musicians, nurses, and patients—many of whom, like Peters herself, lay claim to more than one of these titles. In addition to an opening section on the use of art in medicine throughout history, there are chapters on Body, Sight, Space, Sound, Color, and Action.

Body addresses the disfiguration that comes from invasive surgeries and asks: What if people felt empowered to ask for a more beautiful scar, and what if their surgeons understood exactly what they were asking for instead of looking back curiously or blankly? The inhumanity and loss of agency one might feel after a disfiguring surgery can be hard to live with. Many women have taken to decorating their flat, scarred chests post-mastectomy with beautiful tattoos of flowers, butterflies, or jungle scenes—reclaiming their bodies after the lifesaving, if dehumanizing, treatment.

The sound chapter looks at “one of the oldest tools in medicine,” according to one quote in the book (even before we discovered the wonders of focused ultrasound). The book even comes with its own Spotify soundtrack, though Peters doesn’t tell you that until you reach page 110, which is a pity since you could have been listening to it all along.

But not all the modern sounds of health care are so moving. Some are downright unwelcome. Hospitals are places of extreme sound pollution and dissonance, from the harsh, multiple, and constant alarms, to metal clanging sounds, to loud arguments, and moaning patients. According to Peters, the ICU’s ambient noise clocks in around 80 decibels, and we know from a 2014 study that a single ICU patient triggers an average of 187 alarms per day, mostly false.

Once, when hospitalized, a musician named Yoko Sen “picked up the C note of one of her monitors, combining it with a high-pitched F-sharp alarm from another to make a diminished fifth, a type of dissonance so noxious that for centuries it was called a ‘devil’s tone.’” She was distressed by the thought that it could be the last sound she ever heard. So after she was discharged, she became an artist in residence, first at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington D.C., and later at Kaiser Permanente, which ultimately led to her founding a company called Sen Sound, whose mission is to innovate the sound in health care environments using human-centered design.

The colors of medicine

In the chapter on color, Peters recounts the brilliance of Florence Nightingale, an early systems thinker who founded modern nursing and was an extremely effective hospital organizer and reformer. Nightingale wrote, “The effect in sickness of beautiful objects, of variety of objects, and especially of brilliancy of color, is hardly at all appreciated. Such cravings are usually called the ‘fancies’ of patients. [But often], their (so called) ‘fancies’ are the most valuable indications of what is necessary for their recovery.”

For 100 years, Johnson & Johnson was mass producing Band Aids, but it wasn’t until the Black Lives Matter movement that they were made available in an inclusive range of skin tone colors.

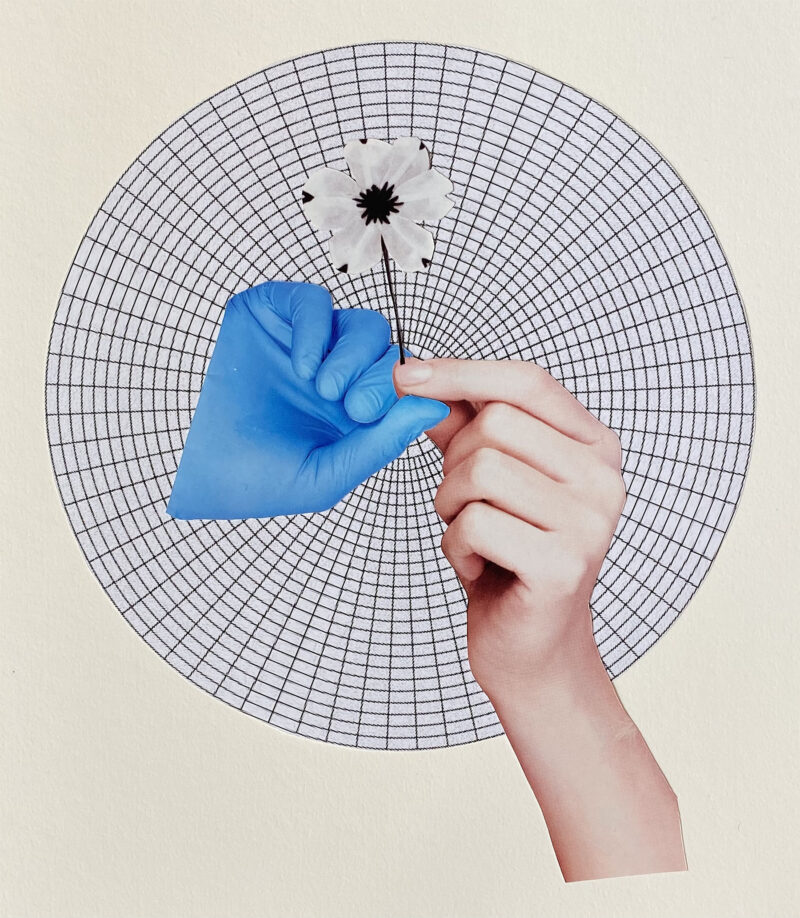

For those who have wondered how we ended up with sterile whites, or the hospital green of yore, Peters offers a section of fun facts about color in which she reveals, for instance, that for 100 years, Johnson & Johnson was mass producing Band Aids, but it wasn’t until the Black Lives Matter movement that they were made available in an inclusive range of skin tone colors. Black used to be the color both physicians and the clergy wore up until 1900, when widespread acknowledgement of germ theory led to a switch over to white, signifying an environment and a practice that is both clean and sterile. Even today, the white coat ceremony is both a rite of passage and a way of making medical students appear less scruffy, cleaner, and more professional looking.

After sterile white, blue would seem to be the color of modern medicine. There is a specific shade of blue used in communications throughout medicine and biotech which corresponds to the brand color of Epic, one of the largest electronic health records systems in the United States. Blue is also the color of the Viagra pill, which Peters calls “one of the most identifiably branded pills on the market.” Why are bedpans and water pitchers all dusty rose? We have Medegen Medical Products/Minigrip, a Tennessee supplier of inpatient products to thank for that color choice.

Another practice that gets attention in Artists Remaking Medicine is activism. Examples include the episode of comedian John Oliver’s show in which he partnered with the activist art group RIP Medical Debt to create a debt collection company that bought up and retired $15 million of actual medical bills. Peters also recounts some of the escapades of the art collective MSCHF—which if you didn’t know better, could be the name of a disease-causing protein. Pronounced “mischief,” MSCHF is an avant garde group of artist/activists known for using art, fashion, merchandise, and media to call out the insanity and absurdity of modern life. In one project, Three Medical Bills, they used oil on canvas to paint actual line items from real medical invoices, ranging from blood draws to “enigmatic discounts” to create large canvases that were displayed in a virtual gallery called Medical Bill Art. Afterward, they sold fractional ownership in the paintings, raising $73,360 that they then used to pay off the medical debt of the three people involved.

Artists Remaking Medicine is a beautiful work of hope for a system that seems beyond hope for many. Health care transformers everywhere should take note and find solace in the seemingly small ideas that could have outsized impacts on the lives of doctors, nurses, and the people they treat.