It feels like we’ve been here before. Here’s why it’s different this time.

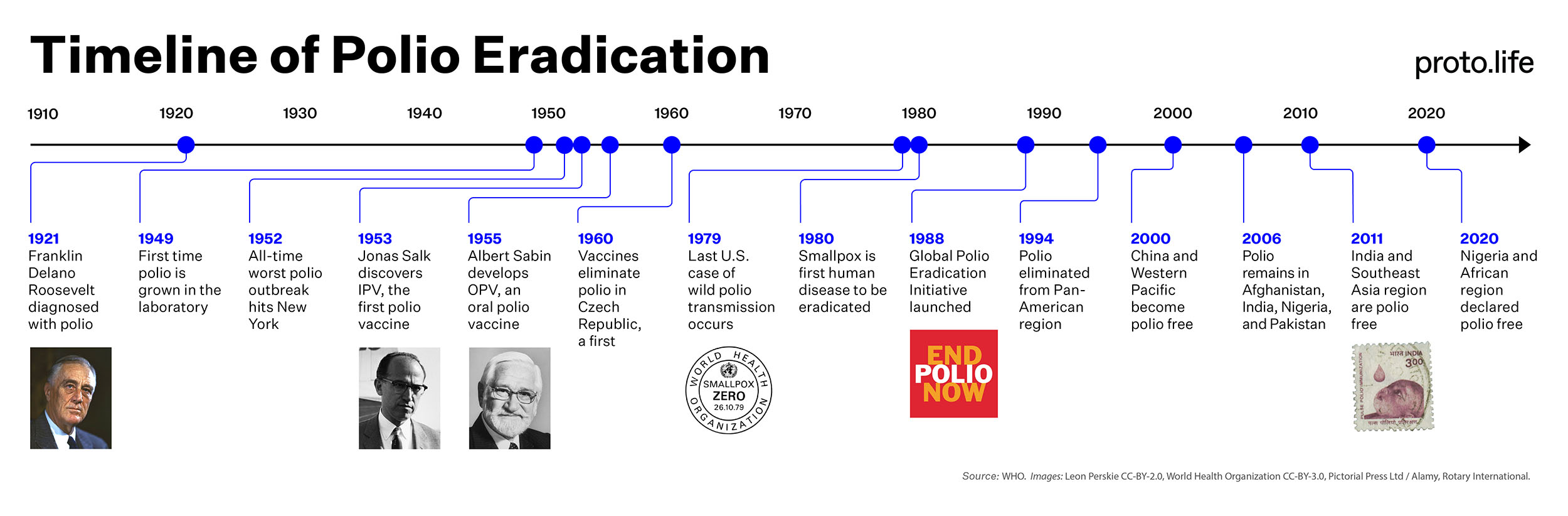

When the modern drive to eradicate polio began in 1988, gasoline was 90 cents a gallon, Ronald Reagan was president, you could still get shot trying to climb the Berlin Wall, and the World Wide Web was nothing more than lunchroom banter between physics geeks in a suburb of Geneva. Globalization, the internet, and global pandemics were all in our future.

That year, some 350,000 people were paralyzed from poliomyelitis, a dreaded disease that conjures up tragic images of FDR in a wheelchair, ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs depicting people on crutches—perhaps the oldest known victims of polio—and mid-century American children encased in iron lungs. Thirty-five years ago it was a global disease, with outbreaks occurring in 125 countries all over the world: across Africa, in Mexico and China, throughout the Soviet Union, and in many parts of Europe.

But 1988 was the year when the world finally said, No more!

Following the adoption of a resolution by the World Health Assembly at the United Nations to eradicate polio within 12 years, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative was launched as a public-private partnership between world governments, NGOs like Rotary International (later joined by GAVI and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), and agencies like the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The initiative sponsored heroic, sometimes Herculean efforts to vaccinate children everywhere against the virus. Since then, we have clawed back caseloads from 350,000 in 1988 to only nine so far in 2023—a decrease of 99.998 percent. Experts are now saying we are on the brink of halting wild transmission completely in the last two regions where it is still active—southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in northwest Pakistan and Nangarhar province in eastern Afghanistan—as soon as this winter.

Ending the transmission of wild poliovirus in the two countries where it still occurs will be a major step toward ending the disease forever. Total eradication, however, will require a little more. Those same areas will have to be carefully monitored for years to make sure no pockets of virus remain. And eradication also necessitates dealing with so-called vaccine-derived polio, which threatens people in several African countries and places like Yemen, where civil wars and humanitarian crises conspire to prevent adequate vaccine coverage.

“We’ve made tremendous progress,” says Carol Pandak, who directs the Polio Plus program for Rotary International, one of the founding organizations of the 1988 eradication initiative. There were three strains of wild poliovirus in circulation in 1988, and we’ve already eradicated two of them completely. The third is confined to a geographically narrow stretch in northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan where the two counties meet. Many experts are confident that it can be wiped out there too—perhaps as soon as this winter.

Eradicating a disease is not like running a marathon—or even moving a mountain. It’s more like strapping a mountain onto your back and then running a marathon.

“We’re far closer than we’ve ever been before,” says Erin Stuckey, the senior program officer for polio with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, one of the partners of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. “I’m definitely optimistic.”

But nothing about eradicating a human disease is easy.

If we don’t end wild polio transmission in southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Nangarhar Province this winter, it would more likely be for implementation challenges rather than scientific or technological ones. Safely accessing those remote populations is enormously challenging, says Roland Sutter, who is a retired former official with the WHO and the CDC and now works as a consultant on polio eradication.

Still, even as his inner scientist casts doubt, he acknowledges the overwhelming gravity of where we could soon find ourselves. “In the unlikely case that the program is successful by the end of the year,” he says, “we have to acknowledge a gigantic achievement, and a major step toward eradication.”

“Everybody is cheering on the program to get to the finishing line,” Sutter says.

What it’s going to take

Eradicating a disease is not like running a marathon—or even moving a mountain. It’s more like strapping a mountain onto your back and then running a marathon.

First of all, very few infectious diseases can be eradicated—only the ones that are human-specific and don’t circulate in other animal “reservoirs.” The viruses that cause influenza, COVID-19, or Ebola, for instance, circulate widely in other animals, which means they are constantly at risk of reemerging.

Second you need an effective way to block transmission, like a good vaccine, and you also need to be able to get it to people all over the world. So ideally your vaccine should be shelf-stable and able to survive long journeys to places where there may be no refrigeration or electricity—or else you need to have a cold supply chain to get it there. And it needs to be cheap enough to make worldwide vaccination campaigns possible.

Hamid Jafari, the director of polio eradication at the World Health Organization, says that when vaccination campaigns were ongoing in India prior to polio’s elimination there a dozen years ago, the total cost for each child vaccinated was around 20 cents. Half that was the cost of the vaccine, which in those days was 10 cents a dose. (Vaccination costs vary, however, and to vaccinate children in the more sparsely populated areas of southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Nangarhar province today could cost as much as 10 times that amount.)

Finally in order to eradicate an infectious disease, you need good, adaptable strategies and a whole lot of political will. Polio eradication, just to name a few, has had to meet challenges like civil wars, highly mobile populations, punishing refugee crises, poverty, climate change, rising misinformation, vaccine hesitancy, and population densities that range from incredibly packed to unimaginably sparse.

Yet in spite of all that, Pandak says, “We’re optimistic about being able to eradicate the wild poliovirus in fairly short order.”

“Everyone in the program, from the top to bottom, is pushing for the transmission to be ended this coming low season,” Stuckey says. “Obviously nothing is guaranteed, but I’m as optimistic as I can be about it.”

“These winter months are our best opportunity to finally eradicate the virus,” Jafari says. “If we can sustain the trajectory of the progress we have right now, then I’m very confident.”

Winter is coming—but that’s good

Polio is caused by an enterovirus, a type of pathogen that’s able to survive for prolonged periods in contaminated water. It can even survive for weeks at room temperature—assuming the weather is warm. But the virus is susceptible to cold weather, and its transmission lows always occur in the frigid winter months, so in the cold mountains of northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, the coming winter months give us the best opportunity to find it and snuff it out, experts say.

What happens then? If and when we end polio transmission in these two countries, it will take many more months of anxious and judicious monitoring to detect any new outbreaks. Should no new cases of polio appear and no new virus is detected in sewage samples, eradication will eventually prove out. Following that will be a series of announcements, certifications, and declarations—first by districts and states, then the two countries, then the entire geographic region, and finally the entire world will be declared polio free.

Everything in the 2022–2026 strategic plan that guides the activities of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative has been budgeted with the expectation and ultimate goal of ending the transmission of wild poliovirus completely in Pakistan and Afghanistan this winter as a first step toward that eventuality. Most of the necessary funds have already been raised. A year ago, a pledge drive in Germany resulted in $2.6 billion of commitments from donor governments—more than halfway to the $4.8 billion needed to fully fund the initiative through 2026.

If all goes according to plan, three or four years from now, the World Health Organization could well be declaring polio completely wiped off the face of the Earth. What will that champagne-uncorking moment look like? It’s hard to say because it’s only happened once before, when smallpox transmission was ended in 1977 and declared eradicated in 1980. I like to imagine it as the global health party of the century. A celebration of the future of humanity to which everyone will be invited—not just everyone alive today or in three years, but everyone who will ever be born—only this time without all the feathered hair and disco ballads of the smallpox eradication days.

Or so we hope.

Allow me to address the elephant in the room: As a global health journalist who has written about polio on and off for decades, I recall multiple instances where predictions of polio’s demise were greatly exaggerated. Such claims have begun to carry a ring of here-we-go-again-ism.

The 1988 World Health Assembly resolution called for eradicating polio by 2000. In 1993, when I was in college, a story appeared in the L.A. Times reporting the death of Albert Sabin, the University of Cincinnati doctor who invented the first oral polio vaccine. Commenting to the Times, Hioshi Nakajima, who was WHO director at the time, was still confidently predicting the world would be polio-free by the turn of the century.

The claim didn’t seem extravagant at all. We were five years into the worldwide polio eradication effort at that point, and the triumph of smallpox eradication was still fresh in living memory. But eradication efforts are always complicated by civil wars and armed conflicts, and the early 1990s saw no shortage of those problems in West Africa, derailing the fight against polio there. And the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan ushered in a new chapter of civil war and political instability, with the same results.

By 2000, as I was busy writing my graduate thesis on smallpox eradication, the predictions had changed. Experts then had changed the forecast to predict polio eradication would not occur until 2005. But that didn’t happen either, even though by 2006 we had eliminated wild poliovirus from circulation in all but four remaining countries: Afghanistan, India, Nigeria, and Pakistan.

Another major milestone was reached in 2011 when polio was eliminated from India, a feat many deemed impossible until it wasn’t. The goal seemed closer than ever, but then things took a bizarre turn elsewhere.

Eradication efforts in Pakistan had to be halted after the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) organized a fake vaccination campaign in Abbottabad as part of its search for Osama bin Laden. CIA operatives offered free hepatitis vaccines to children in a compound where the notorious terrorist was believed to be hiding. They intended to use a trick syringe to capture drops of blood during the injections, in the hope they could secure DNA from bin Laden’s children, thus confirming his presence inside the compound. The effort came up short. They didn’t collect the samples they needed, but the U.S. military stormed the compound anyway, found bin Laden, and took him down.

At the end of 2020, there were 140 cases of polio in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and in 2021, there were only six.

However successful the military operation, it caused horrendous blowback for legitimate public health campaigns, including polio eradication. The events further undermined public confidence in vaccines, fueled long-held conspiracy theories linking vaccines to CIA plots, led militants to target legitimate health workers—some of whom were gunned down and killed—and caused the United Nations to suspend polio vaccination efforts in Pakistan. On May 16, 2014, President Obama’s administration announced it would never again condone spies using vaccination campaigns as cover.

And then there was COVID-19. Because of the pandemic, in March 2020, all polio vaccination campaigns were suspended for several months. Health workers were reassigned to helping with the COVID-19 response and polio surveillance was stopped. “The entire polio infrastructure globally pivoted towards COVID,” Pandak says, “both to keep frontline vaccinators safe, but also to keep communities safe, and to support the [COVID-19] outbreak response.”

But COVID-19 may have had unexpected benefits. Increased handwashing, social isolation, and reducing travel during the pandemic may have cut down on the transmission, and the numbers appear to back that up. At the end of 2020, there were 140 cases of polio in Afghanistan and Pakistan, but by 2021, there were only six.

However, Jafari attributes this decline not to coronavirus but to the hard work of the Global Polio Eradication initiative and its partner governments. In Pakistan, for instance, whenever even a single case is seen or a single environmental sample tests positive, it’s been pursued like gangbusters: aggressive investigations, intensification of surveillance, and more vaccinations. That level of commitment is one of the reasons why Jafari and other experts say the finish line is well within reach.

“This is like the [last] 100 meters, the very end of the race,” Stuckey says. “That’s kind of where we are now.”

So what will it take?

There’s little mystery about how to traverse the final mile. A recent report on polio in Pakistan in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report states simply, “Halting the spread of [wild poliovirus] in Pakistan requires that the country maintain its strong commitment to ensuring that every child is reached, vaccinated, and protected from the debilitating effects of paralytic polio.” (Despite numerous requests, the CDC would not make an expert available to comment further.)

Not every analysis is as matter-of-fact.

An independent monitoring board that oversees the progress of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative met this summer and issued its report a few weeks ago. The report finds much to be optimistic about but says the initiative’s goal of interrupting wild poliovirus transmission in Pakistan and Afghanistan this coming winter is “off track” and predicts “with a very high probability that it will be missed” (their emphasis).

The report also predicts the initiative’s second goal—interrupting vaccine-derived poliovirus transmission—will be missed. “The Polio Programme is still in recovery mode from the massive outbreaks of vaccine-derived polio that occurred in 2021,” the report reads.

Outbreaks of vaccine-derived poliovirus occur when the weakened form of the virus used in oral vaccines begins to circulate in communities where not enough people are immunized. If it circulates long enough, the virus could, over time, mutate into a more virulent form. A new vaccine however, called nOPV2, was rolled out during the pandemic and granted emergency use authorization by the World Health Organization in March of 2021 that should help. It is genetically more stable and less likely to cause such outbreaks, and so far some 700 million doses have been administered.

Vaccine-derived polio cases are still a major challenge, however, because the majority of them are concentrated in the Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Nigeria, south-central Somalia, and northern Yemen—all places dealing with various armed conflicts, refugee crises, and complex humanitarian emergencies. “They have a lot of the zero-dose children who have never been vaccinated for one reason or another,” says Pandak.

Two major pushes will be needed to eradicate polio, says Thomas Frieden, the president and CEO of the nonprofit Resolve to Save Lives, a member of the independent monitoring board and a co-author of the new report. First, he says, we have to finally end the spread of wild poliovirus in Afghanistan and Pakistan. And then we have to wipe out the vaccine-derived polio cases in Africa and places like Yemen. Neither of those will be easy, even as they’re within reach.

“With enormous effort and despite many challenges that couldn’t have been anticipated when the polio eradication campaign was launched nearly 40 years ago, the world is closer than ever to eradication,” Frieden says.

“However, that doesn’t mean it’s close.”

Many dreams of saving children

If we do succeed in permanently wiping out polio, it will be the culmination of a century’s worth of remarkable events that started with an American doctor named William Hallock Park, a high-ranking official with the New York City Department of Health at the beginning of the 20th century. Park had helped to develop mass-produced diphtheria antitoxin, and he was nearing retirement in 1931 when he urged a young 25-year old medical resident named Albert Sabin to pursue what would become his life’s work—to do for polio what Park had done for diphtheria.

Sabin wasn’t the first to climb that mountain, however. Jonas Salk discovered the first polio vaccine at the University of Pittsburgh in 1953, an intramuscular injection now called IPV because it’s made with inactivated poliovirus. Two years later Sabin followed suit, discovering his live, oral polio vaccine (OPV) at the University of Cincinnati in 1955.

That same year, Salk’s IPV vaccine was tested in a massive study involving 400,000 children—the largest U.S. clinical trial ever at the time. By any measure, it was a monumental success. The results were published on April 12, 1955, and Salk’s vaccine was licensed the very same day. Within two years, U.S. cases of polio plummeted tenfold, from 58,000 a year in the early 1950s to only 5,600 in 1957. By 1961, only 161 cases occurred in the United States.

Salk became one of the most celebrated doctors in human history. He once quipped that he never needed to win the Nobel prize because everyone already thought he had. He also famously, in what seems a stunner today, refused to patent his invention, explaining this to journalist Edward R. Murrow once by asking, “Could you patent the sun?”

If any poliovirus remains and is not wiped out, it’s almost a mathematical certainty that it will come roaring back.

The success of Salk’s IPV vaccine, however, made testing Sabin’s vaccine much more complicated. He couldn’t obtain permission to conduct clinical trials in the United States, so the earliest trials were carried out in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Sabin then traveled to the Soviet Union, where authorities conducted tests of his vaccine on 20,000 kids in 1958 and another 10 million children in 1959. They also tested the vaccine on 110,000 Czechoslovakian children from 1958–1959, which proved the vaccine safe and effective and led to polio elimination in that country a year later—a world’s first.

Sabin, like Salk, never tried to commercialize or patent his vaccine, calling it “my gift to all the world’s children.”

And it was. Tens of millions of people are walking the streets today who would have been paralyzed had it not been for the vaccines, the eradication initiative, and its countless associated partner nations, politicians, health ministers, volunteers, doctors, nurses, donors, lab workers, local guides, community leaders, and brave children all over the world.

So one might ask, given all that success, do we really need to continue, especially given how hard this final mile has been? Experts resoundingly agree the answer is yes. They go so far as to say we have a moral imperative to finish the job because if we don’t stop the virus now—if any poliovirus remains and is not wiped out—it’s an almost mathematical certainty the disease will come roaring back.

“We will go through another cycle of spread and outbreak because it is an epidemic-prone disease,” says Jafari. “As long as transmission survives, we’ll see another cycle somewhere.”

Dealing with a resurgent polio crisis on several continents would be a disaster. It could cost some $1 billion per year, Pandak says—and that doesn’t even take into account the loss of life, paralysis, and human suffering associated with the disease. “The cost of not completing eradication is the human suffering,” Pandak says. “Were we to stop now, you could have as many as 200,000 children paralyzed every year within the next 10 years.”

Even if that knowledge adds urgency to the work, Pandak says it’s still going to take a lot to get there—more funding, sustained political will, judicious monitoring, rapid responses, and high-quality campaigns to get vaccines to children.

Pandak recalls one experience she had several years ago, giving oral drops of vaccine to a little baby in India. “I remember I was holding her in my arms,” she says, “very focused—you’re just looking at their little mouth as you’re putting the drops in.”

Once she was done, she went to hand the baby back to her parents. But looking up, she realized it was another child who was there waiting—the baby’s big sister. She had brought her to get the vaccine, Pandak thinks, because her parents couldn’t.

So, Pandak says, “I handed her back to a six year old.”

The story says a lot. If our generation’s inescapable moral responsibility is to complete what Salk and Sabin started, and finally eradicate polio, it’s for our children and the future we want to leave behind for them—and sometimes with their help.

Editor’s note: This story originally reported that in 2023, there were seven cases of polio in Afghanistan and Pakistan combined. After publication, we discovered the official count has been increased to nine, and we updated the 4th paragraph to reflect that new number on 10/23/23.