Trying to stay young isn’t just futile: it’s also bad for you. Here’s how to think about aging in the era of ultra longevity.

In the 20th century, thanks largely to clean water and antibiotics, the American lifespan increased by 30 years. Who doesn’t want even more, if new technologies like gene editing and nanomedicine can safely put them within our grasp? As proto.life describes it, it’s the most important story today: “how biology and technology are coming together to help us all live healthier, happier, and longer lives.” But the challenge for all of us, no matter our age, is to not frame it as an “anti-aging” story. Here’s a pro-aging take on each of those modifiers — healthier, happier, and longer lives — starting with life extension itself.

Goal #1: longer lives

Aging isn’t something debilitating that bushwhacks us somewhere north of mid-life. Aging is living and living means aging. Nor is aging a disease; otherwise life, too, would be a disease. As British journalist Anne Karpf put it to NPR’s Brian Lehrer, “You can no more be anti-aging than anti-breathing.” Part of the distinction is semantic: make the target “age-related functional decline,” not “aging.” The “root cause of aging” is the passage of time, not cell senescence. At the end of all that living, we die. If the goal is to prevent death, whether by freezing ourselves in cryonic vats or by achieving what scientist Aubrey de Grey calls “longevity escape velocity,” let’s describe it accurately: not anti-aging but anti-dying.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m intrigued by the regenerative potential of tissues and organs, and all in favor of more research into the biology of aging. Until we understand what happens to our cells and organ systems far better than we do now, no health promotion strategy will have much of an effect on average life expectancy and maximum lifespan. More years of healthy life would be wonderful. But just as the enemy is disease, not aging, the goal needs to be health, not youth.

Goal #2: healthier lives

I like the way bio-entrepreneur Craig Venter puts it in a proto.life article called “The Anti-Aging Habits of Longevity Experts”: “I’m trying to use the best of scientific knowledge to be as healthy as I can for as long as I can.” Like all the experts quoted in that story, Venter is engaged in the most effective “anti-aging” behavior of all: pursuing a goal. Long-term studies show that even with brains full of plaques and tangles, some people stayed sharp to the end. What did they have in common? A sense of purpose. What’s the biggest obstacle to having a sense of purpose in late life? A culture that tells us that getting older means shuffling offstage. Aging with purpose means rewriting that script.

A growing body of fascinating research shows that attitudes toward aging have measurable effects on how our minds and bodies function. People who don’t equate aging with disability and decline walk faster, do better on memory tests, and are more likely to recover fully from severe disability. That’s why the World Health Organization is developing a global anti-ageism campaign: to extend not just lifespan but “healthspan.” Not coincidentally, people with positive feelings about getting older also live longer — and they live better.

How worried are you about getting older, and why? Has what you dreaded come to pass? Check your age bias. It segregates us, pits us against each other, and fuels needless fears — and it might be your biggest health risk.

Goal #3: happier lives

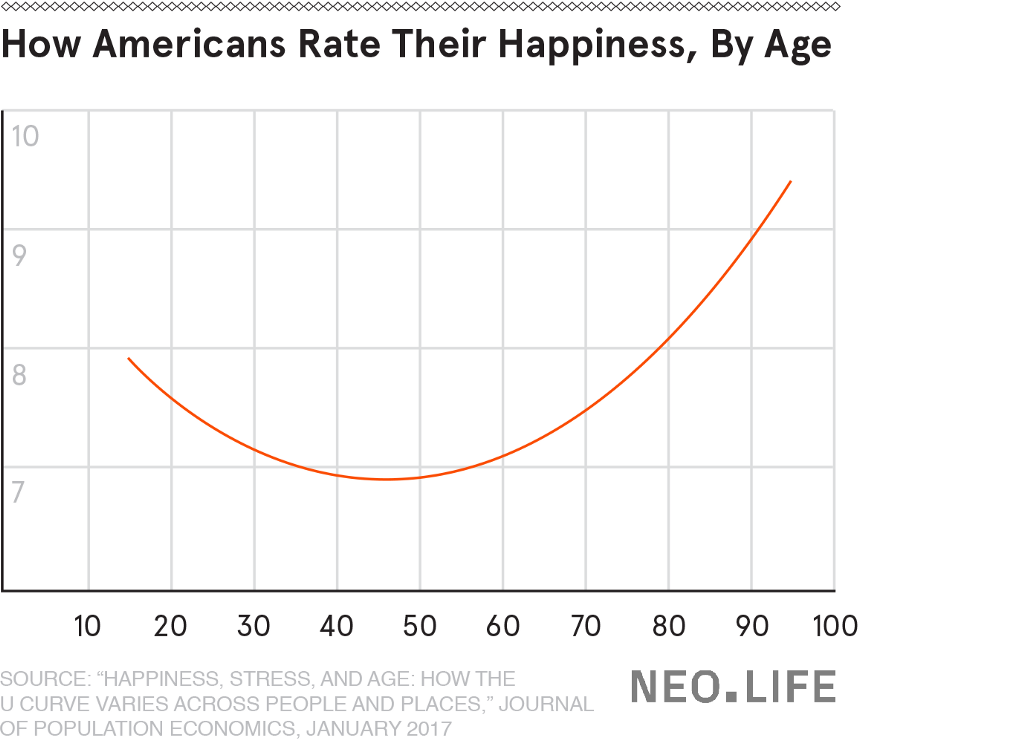

Even in Silicon Valley, tied with Hollywood as the most ageist place on the planet, people know that tans and Teslas aren’t what make us happy. What does? Aging itself. Study after study shows that people are happiest at the beginnings and the ends of their lives; Google “U shaped happiness curve.” You don’t have to be a Buddhist or a billionaire, because the curve is a function of the way aging itself affects the brain. We get better at dealing with negative emotions like anger, envy, and fear. The knowledge that time is short makes us focus on the present and spend our time more wisely — and living in the present is why the very young and very old enjoy life the most. That’s what the “mindfulness” mania is constantly reminding us, and why so many myths couple immortality and misery.

As wise people across countries and cultures continue to remind us, there’s no present if there’s no ending. Not dealing with dying is a way of not dealing with living. Who wants more life, if it indeed becomes ours for the taking, if it comes without self-awareness or fulfillment or contentment? More reason to drop the anti-aging rhetoric, and the denial that fuels it. It keeps us from enjoying the present, and it feeds the narrative that aging well means looking and acting like younger versions of ourselves. Only the well-off can pursue that strategy, which is doubly discriminatory for women — and futile.

Imagine a new goal: age equality

Perhaps, not too long from now, we’ll be able to make the body of an octogenarian function as well as of that of a 30-year-old. That’ll be fantastic, especially if the advances become accessible to all. But 85 won’t be the new 30. It’ll be the new 85. And even the fittest octogenarians will be second-class citizens until we challenge the last socially sanctioned prejudice. Making the most of the new longevity means ending ageism.

Why does “anti-aging” sound normal and “pro-aging” sound weird? Because we’re brainwashed by a ruthless consumer culture. Who says wrinkles are ugly? The multi-billion-dollar skin care industry. Who says perimenopause and “Low T” and “mild cognitive impairment” are medical conditions? The trillion-dollar pharmaceutical industry. Unless you count sunscreen, no “anti-aging” remedies are effective, and many have proven harmful. Aging is not a disorder. Yes, it strips us of cartilage and shortens our telomeres, but it also confers confidence, contentment, even grace. You can’t live longer without getting older — and that’s a very good thing.

Ashton Applewhite is the author of This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism.