This mysterious end-of-life energy surge could teach us about memory, cognition, and the search for dementia treatments.

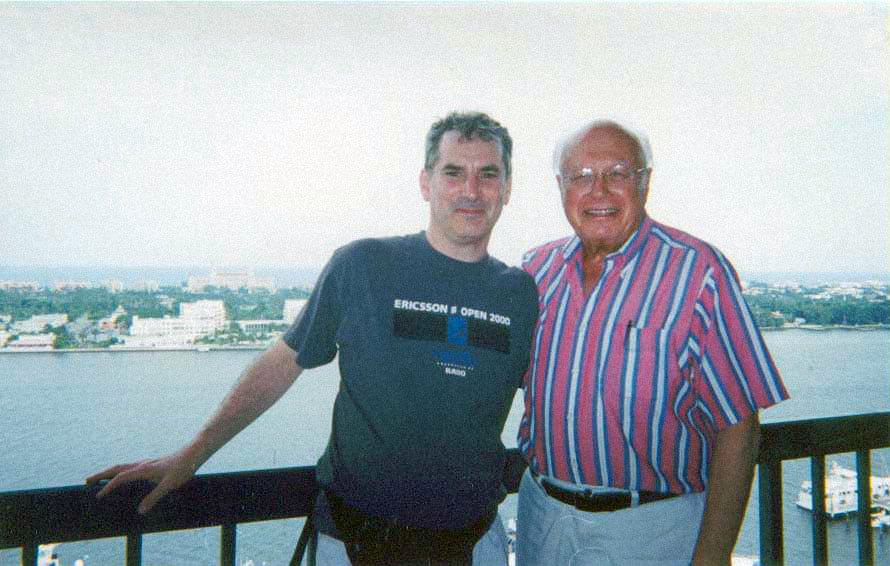

Several days before my uncle Marty passed away in 2017, he had a request. He was in the hospital for congestive heart failure, admitted with jaundice and some problematic blood counts, and had been weak and sleepy, barely communicating until that day.

The hospital had suggested the family consider hospice. He was almost 95; his heart was not going to improve; it was time to say goodbye. Rather than slipping quietly away, my cousin Helene told me, “Suddenly, my dad revved up with energy and purpose. He just wanted to get out of bed and walk the hallways. We had been told that he was not permitted to leave the bed without a nurse’s assistance.”

But the nurses were too busy with other patients and had ignored him for hours. His two daughters begged them to help. Finally, around 11pm, they guided him out of bed. One nurse attached a special belt with a loop she held to keep him from falling. The other got behind him with a wheelchair. But Marty was energized by his anger and frustration. “Let’s go,” he announced, starting at a brisk pace, walking back and forth, up and down the hallway so fast that the nurses could not keep up. “He was dragging the first nurse down the hall, the second ran with a wheelchair,” Helene says. When he reached the door to his room, Marty said, “Now, I’m ready to go back to bed.” He was exhausted but he wasn’t about to let the nurses see that.

Early the next morning, he called his family and asked them to get to the hospital now. When they arrived, he said in a clear voice, he was done with being poked and prodded by the hospital staff. He said, “I just want to go somewhere quiet, where I can eat or sleep or do what I want, surrounded by my family and just float away.” He went to hospice later that day and died two days later.

What the nurses and my cousins saw was an episode of terminal lucidity, an extraordinary phenomenon that Michael Nahm, a biologist and research associate at the Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health (IGPP) defines as “the unexpected surge of mental clarity shortly before death.” Terminal lucidity is also known as an energy surge, paradoxical lucidity, rallying, or sometimes “the rally.” It is one of the lesser-known end-of-life experiences, which include deathbed visions, apparitions, and near-death/out-of-body sensations. It can occur in people who die with dementia but also in people with healthy brains but are confused, dull or unconscious because of their overall poor state of health, Nahm says.

There have been reports of terminal lucidity in the medical literature dating back more than 250 years. In a 2012 journal article, Nahm detailed 83 case reports of people suffering from brain abscesses, tumors, strokes, meningitis, dementia, schizophrenia, and affective disorders who experienced terminal lucidity. Nearly 90 percent of the cases he cited happened within a week of death, and almost half occurred on the final day of life.

A hangar steak at death’s door

Milena Zaprianova, a nurse who serves as clinical director for the hospice care team from VNS Health, notes that terminal lucidity is well known among hospice staff and that almost every clinician on her team had seen or heard about a case. “Sometimes it is very striking, sometimes not,” Zaprianova says. “The most dramatic case noted by our team was a patient who was bedridden, did not speak, and was unresponsive. One day the patient got out of bed, went to the dining room, had a steak and engaged with family. The patient then returned to bed, went to sleep, and died the next day.”

Terminal lucidity is most often seen in people with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s—one of the reasons why it’s also known as paradoxical lucidity. But it is also seen in dying people who don’t have cognitive issues, as was the case with both my dad and my aunt. “A pathological brain condition is no prerequisite for the occurrence of terminal lucidity,” Nahm says.

According to Dazel Gamit, a nurse with the hospice care team from VNS Health, “terminal lucidity is more dramatic in people with diseases such as Alzheimer’s because their sudden clarity is surprising to their families.”

In the packets of materials the hospice team gives to family members, information on terminal lucidity is often included. “Family members are usually unaware of these episodes, and we want to prepare them as well as alert them that their loved one in hospice is not getting better or even cured, which is a common assumption,” Zaprianova says.

Craig Blinderman is the director of Adult Palliative Care Service at Columbia University Medical Center. He notes that although there is no explanation for it, some in the field believe that terminal lucidity is due to the liver shutting down during the dying process. “The thinking is that this causes hormone-like compounds to be released to the brain which ‘awakens’ the dying patient’s consciousness for a brief time. Or it might be part of the delirium process, Blinderman says.

One reason it is difficult to study terminal lucidity is that the goal of care at the end of life is often to make patients comfortable, even if that means being completely sedated, Blinderman notes. “We’ve had many family members rush to the hospital to see their loved one before he/she dies and want us to wake them up to say goodbye. We don’t do that. The patients’ needs come first.”

A hard to study phenomenon.

How prevalent is terminal lucidity? It’s a hard question to answer with any precision because of the challenges of studying terminal lucidity, according to Douglas Vakoch, a clinical psychologist and director of the Berkeley, California-based practice Green Psychotherapy.

“It’s difficult to conduct rigorous medical research on terminal lucidity because of its timing,” Vakoch says. Typically, it doesn’t last long—often only hours or days—so scientists don’t have much time for close, careful observations.” Vakoch also notes that since terminal lucidity occurs during some of the most precious days of a person’s life, gathering data on cases is difficult because people who experience an awakening are almost always otherwise incapacitated with dementia. They are not able to consent to a study, so the family would have to. But it’s often grossly insensitive to ask family and friends questions about their loved one’s experience during their final hours.

“The fleeting nature of terminal lucidity, combined with the ethical challenges of conducting end-of-life research, means we have a woefully limited understanding of the phenomenon,” Vakoch says.

Studying terminal lucidity might facilitate the development of novel therapies for dementia.

However, the reluctance to do research on terminal lucidity is changing. Vakoch notes that one workaround is to rely on case records and reports from clinical staff who are tending to people in the end stages of life, rather than family members. He notes a 2022 study of 33 health care professionals in which 73 percent of participants witnessed terminal lucidity. They reported that 31 percent of the events they witnessed lasted several days, 21 percent lasted one day, and 2 percent lasted less than a day. In 79 percent of the events, the person engaged in unexpected activity, 22 percent died within three days, and 15 percent held out for up to three months of the event.”

In collaboration with the National Institute on Aging, NYU Langone Health is recruiting people with severe dementia who are close to the end of life for a study to explore why and how some people with severe end-stage dementia regain the ability to recall certain memories, verbally communicate, or recognize people. The study will be divided into two phases. In the first phase, the research team will collect sufficient and necessary data through an online survey and focus groups as well as assess the safety and feasibility of using symptom diaries (also known as daily trackers or journals) and real-time video EEG monitoring (vEEG). After a preliminary review of the study procedures, the principal investigator, Sam Parnia, will move onto the next phase whose goal is to expand and refine the study and create a definition and measurement scale for paradoxical lucidity in advanced dementia. Parnia’s research into what happens when we die has been the subject of an article in this magazine.

For the current study, Parnia notes that “although the phenomenon of paradoxical lucidity (another name for terminal lucidity) has been widely witnessed by many health care workers and caretakers of people with end-stage dementia, very little is known about why these events occur and what occurs in the brain during these events. This ability to regain previously lost memories and behaviors, for even a short period of time, suggests there may be some aspects of dementia that are reversible. The knowledge we gain in this study may potentially provide tools for future research and treatment options for dementia patients.” Parnia said that the study team will also use a survey and focus groups that will evaluate and better understand lucidity events observed and witnessed by health care providers and families who are likely to be involved in the care of people who are terminally ill.

“The common unresolved question for both of these areas of research is how do you have lucidity at a time when the brain is assumed to not be functioning?” Parnia says. “A major subgroup of people who go through this have had advanced end-stage dementia and maybe have had no lucidity for years.”

Under a five-year grant from the National Institute on Aging, Parnia and colleagues are aiming to create the first-ever definition and measurement scale for terminal lucidity. “The downstream effect of this is that we might be able to identify new pathways for lucidity in patients with dementia. We may also be able to find new ways to treat disorders of consciousness as well as better understand the cognitive experience of death, what it’s like to approach death,” he says. “So it could further multiple goals.”

Hope for new treatments

Researchers hope that a better understanding of terminal lucidity will lead to a better understanding of memory and cognition and even the development of new treatments for neurodegenerative illnesses. In his 2012 review article, Nahm predicted that “better understanding the processes involved in memory and cognition processing might be gained through in-depth studies of terminal lucidity.”

One of the most under-studied aspects of the phenomenon is how these awakenings affect caregivers and the loved ones surrounding the beds of people who suddenly emerge from their end-of-life lethargy or unconsciousness with sometimes laser focus clarity. Is that a comfort to their families? Could it be traumatic?

“Increased awareness of unusual end-of-life experiences could help physicians, caregivers, and bereaved family members be prepared for encountering such experiences, and help those individuals cope with them,” Nahm wrote in his 2012 article.

Studying terminal lucidity might also facilitate the development of novel therapies for dementia. If we can better understand the biochemical mechanisms that cause someone to awaken in their final hours, could we target those same pathways to develop new drugs for Alzheimer’s, for instance?

When I asked my cousin Helene what Uncle Marty’s episode of terminal lucidity meant to her (and her mom and sister) she said, “My dad gave us a tremendous gift by removing any responsibility or guilt we might have felt for choosing hospice. He was in charge of his decision and his sudden clarity and strength convinced us to let him go on his own terms.”

“Let’s go,” he had said that last day in the hospital, dragging his nurse on that final walk.