Harvard’s new Thich Nhat Hanh Center for Mindfulness in Public Health aims to explore how the ephemeral could change physical and mental health.

When I heard that the Harvard School of Public Health was launching a center for mindfulness last month, I was skeptical. The place was named for the renowned Buddhist monk Thích Nhất Hạnh, and if I’m not mistaken, Buddhism encourages acolytes to embrace humility and humanity, let go of ambition, and quit questing after earthly goods—all of which seems like an uneasy fit for Harvard, a brand associated with ambition and achievement, elitism and exclusivity. I assumed Thích Nhất Hạnh was turning over in his cremated ashes.

At the same time, the health benefits of meditation interest me personally. As someone with major depressive disorder, a chronic illness that destroyed my ability to sleep for close to two decades, I’m aware that meditation is one of the few things proven to help ease depressive symptoms, other than regular exercise and antidepressant use. These days, I’m better—finally on a good cocktail. Even so, I can use all the help I can get, so I remain interested in meditation—especially because I’ve found that counting my breaths (“meditation lite,” maybe) helps me get back to sleep when I’m having trouble, as I often do. Still, though I exercise every day for my mental health as much as anything else, I find it a lot harder to sit still and meditate. So when my editor asked me to cover the inaugural day of Harvard’s Thich Nhat Hanh Center for Mindfulness in Public Health, I went with a mixture of interest and resistance.

When I arrived at the conference, one of the first things I noticed at the well-attended event was a plurality of wealthy ladies. Decked out in their fancy clothes and expensive jewels—their money evident in their goddess-like locks too—a few posed for selfies with the monks visiting from some of the monasteries Thích Nhất Hạnh founded. The monastics, in their long brown Trappist-like robes went along gamely—and hey, they need donations, and must know their audience.

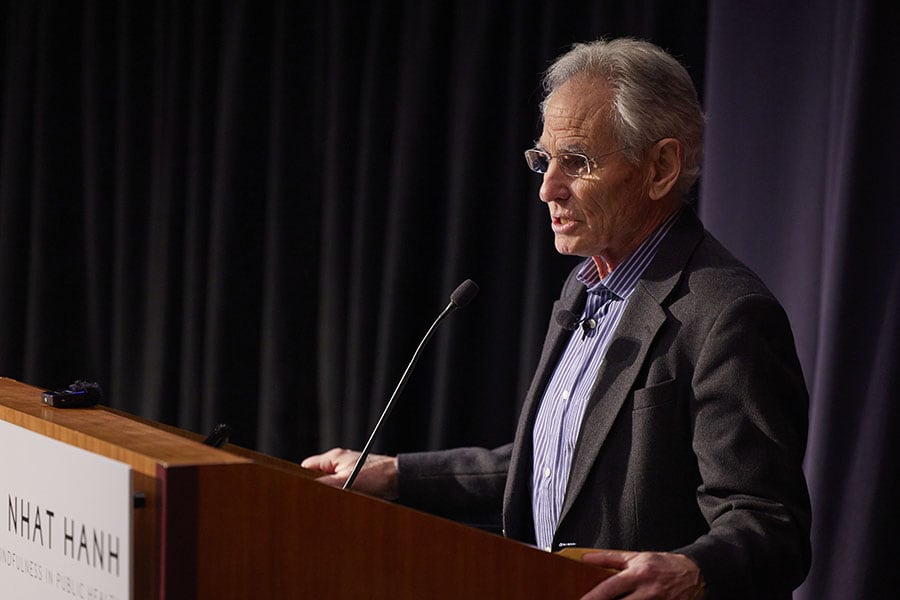

During the daylong series of talks, the heads of other university-based centers around the world voiced some skepticism of their own, even if the particular concerns they mentioned were different from mine. What came up first, however, was a narrative about the center’s founding, which indicated that Thích Nhất Hạnh would be more than okay with his name being used to brand Harvard’s new center. The whole thing was his idea, in fact. He suggested it a decade ago, during a 2013 visit to Boston, when he met with a couple of Harvard-affiliated public health experts whom he knew personally. He’d gotten to know Walter Willett—a professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health—when Willett, then pursuing his M.D. at University of Michigan Medical School, invited Hahn to the Ann Arbor campus way back in 1968, to discuss the Vietnam War. (Nhất Hạnh was the only person nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King, Jr., in recognition of Nhất Hạnh’s work protesting the war.) The spiritual leader also knew Lilian Cheung, the director of mindfulness research and practice in the Department of Nutrition at Chan. They met in 1997 during a retreat in Florida, and they would go on to co-author a 2010 book together about mindfulness and nutrition.

“Mindfulness is mono-tasking.”

Willett is now director of the new Center for Mindfulness. Cheung is the co-chair of the center’s board. As for why it took so long, that may have had something to do with finding the money. But perhaps moved by Nhất Hạnh’s death in January 2022, an anonymous donor pledged $25 million, and by August 2022, Harvard had begun to talk about the upcoming launch. What’s also true is that mindfulness is having a moment, including in academia. Consider, for instance, that as of May 2, 2023, PubMed listed 25,919 peer-reviewed, scholarly journal articles published worldwide that included the key word mindfulness.

Many of those reports have shown that meditative practices can be very helpful for people suffering from mental illness. One of the day’s most compelling speakers—Eric B. Loucks, the director of the Mindfulness Center at the Brown University School of Public Health—cited a few of the most significant studies along these lines, namely: the 2017 meta-analysis that showed mindfulness-based stress reduction has a small but significant effect on improving mental health and quality of life, including social functioning; a 2016 meta-analysis that found mindfulness-based cognitive therapy was effective in preventing relapses for those with major depressive disorder; and a 2022 JAMA study demonstrating that mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety disorders held their own (i.e. were “non-inferior”) against escitalopram, a commonly prescribed anxiety drug. Another notable speaker—Chân Pháp Lưu, a monk who graduated from Dartmouth College—talked about experiencing a severe depression when he was 24, which led him to Buddhism. “Through meditation, I was able to create joy inside myself,” he told the crowd. The relief was so meaningful that he devoted himself to the monastic life.

All the compelling data surely helps to explain the public’s growing interest in meditation—evidenced by the popularity of Calm and Headspace, two mindfulness apps which guide users through device-based meditation sessions. A 2022 study predicted that by 2026 the meditation apps market will increase in value, relative to 2021, by more than a billion dollars. But what’s also causing the venture-capitalist wolves to salivate is the massive number of people suffering from stress, anxiety, and mental illness. A recent report issued by the World Health Organization looked at 2019 numbers and found that nearly a billion of us on the planet—970 million people, one human being in every eight—live with mental illness, most commonly with depressive disorders or anxiety. The unemployment, general uncertainty, and loss of life that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic only seemed to exacerbate the situation, not surprisingly: A 2021 look at data found that anxiety and depressive disorders increased worldwide by 26 percent and 28 percent, respectively at the height of the pandemic.

All this said, just because an app is popular doesn’t mean it’s effective—and here’s where a lot of the day’s skepticism came in, rightfully so. “Do we want multimillion, billion-dollar companies telling us what mindfulness is?” said one of the day’s most charismatic speakers, Nicholas Van Dam, director of the Contemplative Studies Centre at the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences in Australia.

Personally, I don’t want billion-dollar companies telling me anything, though I know they’re always finding new ways to get through the cracks. Nonetheless, as Van Dam pointed out, money doesn’t automatically translate into mindfulness—and a download doesn’t lead to instant enlightenment either. In fact, a 2019 study of popular mental health apps, including mindfulness apps, looked at the use of 93 different Android apps that had each been downloaded more than 10,000 times. It found that only 4 percent of users who downloaded one opened it again after 15 days. The researchers behind a 2022 meta-analysis looking at 145 randomized controlled trials involving some 47,940 participants found much the same. Phone-based interventions for mental illness, including meditation apps, “failed to find convincing evidence in support of any mobile phone-based intervention on any outcome,” they wrote in their report.

At the same time, it’s worth being mindful of the fact that meditation approached the old-fashioned way doesn’t always blow people’s minds in a good way either, according to a group of British, Brazilian, and American researchers who conducted a meta-analysis of 83 clinical studies of meditation in 2020. Almost one million people in the United States alone, or roughly five percent of people who try meditation, may have an adverse reaction—like psychotic or delusional symptoms, fear or terror, or suicidal ideation. And that five percent probably doesn’t include people like me, who felt even more like a failure during the worst of my depression after I failed to “succeed” at meditating. My editor tells me one doesn’t succeed or fail at meditating—one merely begins, and then practices, drawing the mind back in whenever it wanders. But I didn’t know that at the time.

Our increasingly phone-based way of life may be creating problems for us outside of bad apps and poor posture, as one speaker, Diane Gilbert-Diamond, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine, discussed. High levels of media multitasking—like texting and using social platforms at the same time—have been associated with a higher risk of obesity in both college-aged people and pre-adolescents. That may have to do with all the food ads flashed at them online.

“Multitasking can reduce our attention to how we’re feeling, and increase the doorways to [bad] influences,” Gilbert-Diamond said—the implication being that the less in tune we are with our stomachs, the more likely we are to overeat. “Mindfulness is mono-tasking.”

Her talk helped me make better sense of something that initially struck me as odd about Harvard’s new center: It will be run under the auspices of the Department of Nutrition—as perhaps you might have guessed, given Willett’s and Cheung’s credentials. Harvard wasn’t all that much help in explaining why that would be, beyond giving me a pro forma statement. “We plan to research how mindfulness practices interwoven into daily living, mindful design of dining spaces, menus, and shared experiences around food can contribute to healthy longevity,” the statement read. “[And we will study] nutrition, physical activity, and mindfulness to help youth establish healthy and mindful habits that are not only good for their health but also the health of our planet.”

How do you sell one of the oldest, cheapest, most low-tech health solutions on the planet to people who are constantly chasing the newest, most distracting, not-so-cheap high-tech toys?

This planet we live on—our poor doomed planet. Many of the day’s luminaries had our melting Earth on their minds, including well-known author Jon Kabat-Zinn—the medical doctor who has been described as the person “responsible for bringing mindfulness into mainstream medicine,” after he started the mindfulness-based Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in 1979. “The warming of the planet is happening at a remarkable rate, which will have remarkable consequences for public health,” Kabat-Zinn said. Yep (as I’ve written about here and here).

By the end of the day, I was far from relieved of my skepticism—certainly not after I asked to talk to the monks about all this, only to be told that the monastery didn’t want them commenting. (What is the sound of one hand clapping while monks are muzzled by their publicity coordinator?) Nonetheless, I left feeling like the people at the heart of this meditative enterprise are genuinely trying to improve the world—certainly in the case of someone like Brown University’s Loucks, who has practiced meditation for 25 years and emanates a kind of generous peacefulness. He and others seem to want to help others experience the good vibes they’ve found. Judging from the turnout, there’s also real interest and momentum: The 480-seat amphitheater at the Harvard School of Public Health’s Conference Center was packed nearly to capacity—a much bigger crowd than your garden variety Nobel laureate will draw at Harvard. Moreover, as a few of the speakers noted, the fact that Harvard has gotten behind meditation in this big way also seems significant.

The university signaled the seriousness of its commitment through the presence of the dean of the School of Public Health, Michelle Williams, who kicked off the day. During her welcome, she said, “If mindfulness can change physical health, that would be a game changer.” She added, “costs, logistical challenges—neither of those limitations apply to mindfulness. It is available to everyone everywhere.”

But that’s where my skepticism creeps back in. Available does not necessarily mean to be availed of. Available is not the same thing as easy to access—especially in this world of exponentially multiplying distractions, full of AI and algorithms, the majority of which are aimed at making us anything but mindful.

One of the challenges Harvard will have to take on, along with the other organizations represented at the symposium, will be how to get meditation into people’s minds. But how do you sell one of the oldest, cheapest, most low-tech health solutions on the planet to people who are constantly chasing the newest, most distracting, not-so-cheap high-tech toys? And how do you translate it to low-income settings or to different cultures around the world? Beyond that, how do public health gurus protect people from unscrupulous tech magnates who may try to monetize the un-monetizable? People in public health like to say that one of the biggest challenges for health solutions is implementation. This seems especially true of what the center is trying to do. You can’t drop off a crate of mindfulness into a country in the midst of a disease outbreak the way you would doses of vaccine. Healing bodies is hard enough. Calming minds at this moment in history—when we have more distractions than ever and unprecedented challenges like global warming and pandemics driven by strange new diseases—will take more than a center named after a prominent spiritual leader.

At the same time, if any coalition can make a difference, perhaps it’s one working with the resources of the richest university in the world, under the auspices of one of the most inspiring teachers of Buddhism in history.

Editor’s note: After this story was published, our writer was told that Thích Nhất Hạnh would never have asked for the center to be named for him and learned that the failure to make any monks available for interview was a misunderstanding. (Note added 5/7/23.)