Corporate America is embracing mindfulness more than ever as the pandemic rages. But what do they mean by “mindfulness,” and does it work?

As Omicron rages, are you feeling it again? That tightness in your jaw and a redux of existential dread as you search online for another pair of sweatpants—maybe a different color this time—and the latest desktop lights to avoid looking like a Zoombie on conference calls. Then you slam shut your laptop in your home office and shout to no one in particular: This cannot be happening again!

Even before anyone had heard of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, our early 21st-century brains felt fragile as information overload, politics, and roiling economies drove an upswell of people looking for relief. By 2019—which seems like ages ago—millions of people had turned to meditation apps, yoga classes, and lessons in how to breathe with intention. Companies offered health coaching, massages, and self-assessment questionnaires like Clifton’s survey of 34 strengths—all of this lumped by some under the term “mindfulness.”

Then came COVID-19 and a tsunami of pandemic stress. Depression soared by 3x and 40 percent of respondents in a CDC survey reported suffering from at least one “adverse or behavioral health condition.” Last winter, during the second (third?) wave, 49 percent of white-collar workers surveyed by McKinsey & Company said they were burned out—and these were mostly people with decent, well-paying jobs. “A lot of people were barely managing before. COVID put them over the top,” says Camille Preston, a Boston-based business psychologist and the founder and CEO of AIM Leadership. She integrates mindfulness—meditation, breathing, journaling, and stillness—into her coaching and leadership programs.

We remember with a shudder of fear and apprehension those early pandemic days when confusion reigned over everything from masks and testing to leaders who didn’t exactly inspire confidence. But hey, we had Headspace. Not that a meditation app was going to fix everything—although the silky, British-accented voice of co-founder Andy Puddicombe guiding us through sessions on “managing stress in uncertain times” and “feeling overwhelmed” didn’t hurt. Nor did similarly soothing voices on other so-called mindfulness apps that were downloaded by the tens-of-millions as the $2 billion mindfulness industry became one of the few players to show up for people facing the turmoil caused by the virus.

“We saw a huge increase in the use of our apps and programs,” says Stephen Sokoler, the founder and CEO of Journey, a company that provides workshops on improving mental health in the workplace, coaching, newsletters, and meditation apps to the likes of American Express, Sony, L’Oréal, and Disney. “People were trying to adjust to a new reality,” says Sokoler as stress and sometimes conflict spiked among workers abruptly forced to live and work in shelter-in-place worlds. Journey saw engagement in their programs go up from an average of five percent of their client’s employees to over 35 percent.

“Before the pandemic I thought being a leader meant not showing your feelings.”

Preston saw demand for her coaching and leadership services skyrocket, too, among executives like her client Punit Patel. An old-school, tough-guy executive before he worked with Preston, 42-year-old Patel is president of Red Oak Sourcing, a joint venture owned by CVS and Cardinal Health that’s responsible for procuring billions of dollars per year of generic pharmaceutical products. At age 14, Patel immigrated from Kenya with his family and lived in public housing before working hard to earn a doctorate in pharmacy. He then worked his way up from a CVS store pharmacist in Detroit to the C-suite, where his board suggested he seek out leadership coaching. “Before the pandemic I thought being a leader meant not showing your feelings,” he says.

When Patel’s father died of COVID-19 and his mother died too, and after working with AIM Leadership’s Preston for several months, he was able to share these tragedies with his employees. “I allowed myself to be vulnerable, and they really appreciated this,” he says. It improved life at home during lockdown with his wife and girls ages 10 and 12. “The company also has done really well,” he says, “in part because we shifted to a more empathetic approach to balancing business and family and all the rest.”

Productivity also seems to have risen during the pandemic in companies that embraced mindfulness. Most of this data is based on small numbers of test subjects and self-reported surveys, although many mindfulness-oriented companies even before the pandemic were reporting measurable reductions in disability claims, absenteeism, and incidents of strife in the workplace. In 2017 the health insurance giant Humana and Journey teamed up to run a clinical study on workers using the Journey app and found that absenteeism dropped by 51 percent in that cohort. In 2019, a Gallup poll reported that companies with “engaged employees” were 21 percent more profitable and had 41 percent less absenteeism. Yet it’s hard to prove that mindfulness is solely responsible when productivity tips upward. “Not that it’s not doing all of these things,” says Preston. “It’s just hard to quantify it.”

Quantifying the impact of mindfulness in the workplace is tricky in part because the word itself means different things to different people and businesses. It almost always includes meditation. Yet for many, it also encompasses yoga, healthy eating, tai chi, and the like. For some, “mindfulness” is part of the larger “workplace wellness” industry that incorporates financial counseling, wellness coaching, health screening, smoking cessation plans, stress management, dietary advice, Fitbits, and fitness programs. According to Precedence Research, the workplace wellness industry will be worth nearly $55 billion in 2022.

What we mean when we talk about workplace wellness depends on one’s definition, as some researchers and companies lump in more medically oriented tests, programs, and services, like telemedicine, that collectively can bump up money spent on “wellness” into the hundreds of billions of dollars. According to a 2020 Kaiser Family Foundation report, 53 percent of smaller companies and 81 percent of large companies offer some sort of “wellness” program.

But does this outpouring of support for corporate wellness, including mindfulness, come from bosses suddenly feeling warm and fuzzy towards their workers, or from their belief that workers produce more if they’re not balls of stress? “Are they doing this to really help people?” asks economist and author Pippa Malmgren. “Does it matter, if everybody wins?” Malmgren studies and writes about leadership, and was a senior economic advisor to President George W. Bush. “Younger people aren’t interested in just making money,” she adds, “they’re also interested in lifestyle and feeling healthy at work.”

From Buddhist roots to corporate perk

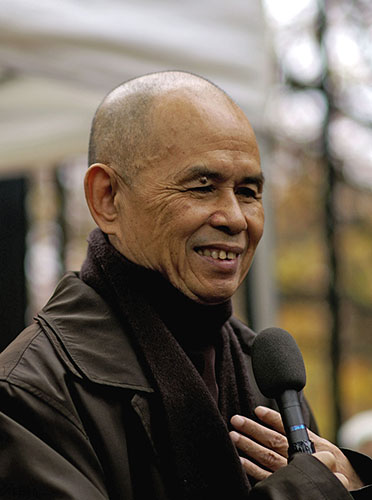

At its core, “mindfulness” comes from the translation of the word sati used by ancient Buddhists in India. It means to train your mind and to remember to follow certain principles to be more engaged in the moment, primarily by using meditation techniques— to be calmer and more aware of our feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations as opposed to letting our minds wander and worry. Practiced for centuries in Asia, sati moved west as “mindfulness” decades ago and became all the rage among New Agers in the 1960s and 1970s, although back then not so much in the C-suite.

Mindfulness’s bumpy path from far out to acceptable began when scientists started to seriously study it in the 1990s. A key pioneer was University of Massachusetts Medical School professor emeritus Jon Kabat-Zinn. His research found that people practicing mindfulness are more focused and less stressed, anxious, and depressed. Scientists have found that mindfulness helps to reduce chronic pain, lowers blood pressure, reduces insomnia, and lessens the body’s inflammatory response to stressors. One 2011 study, which took functional MRI brain scans of 16 people who underwent an eight-week mindfulness course in Massachusetts, showed that meditation and stress reduction techniques appeared to increase the thickness of the hippocampus, which manages learning and memory.

In the early 2000s, companies like General Mills and Google bought into the science and launched mindfulness programs for their hyper-stressed employees and were happy with the results. Soon after, entrepreneurs jumped into the mindfulness fray to found new companies, many of them inspired by their own high-flying founders who experienced burnout.

In 2004 Dan Harris, then an ABC Good Morning America weekend anchor, experienced a devastating panic attack on live television. In 2014 he wrote a bestselling book about how meditation helped him dial back his anxiety, titled 10% Happier: How I Tamed the Voice in My Head, Reduced Stress Without Losing My Edge, and Found Self-Help That Actually Works—A True Story. Later he launched a meditation app, also called Ten Percent Happier. In 2016, Arianna Huffington founded Thrive Global in the wake of collapsing at her desk in 2007 when she was in the thick of running The Huffington Post. “I was stressed out and sleep deprived, and I hit my head on the desk and broke my jaw,” she said a few years ago. “And that was the beginning of me reevaluating my own life and my priorities.”

For Stephen Sokoler, now aged 43, it wasn’t burnout but a palpable sense of numbness several years ago despite achieving great success in business. “I felt like I was a hamster on a wheel,” he says. Then he discovered Buddhism and meditation which led to the founding of Journey in 2015. When COVID-19 struck and Sokoler found himself locked down in New York with his fiancé, now wife, “I kind of freaked out like everyone else. But I had this firm grounding in meditation, which helped me get through it.”

“The harmful effects of stress on your health are not inevitable.”

Stress, of course, isn’t all bad in business or in life. “It’s important for artists and competitors,” says Malmgren. “It’s needed to create and to be successful.”

Health psychologist and Stanford lecturer Kelly McGonigal, author of the 2015 book, The Upside of Stress: Why Stress Is Good for You, and How to Get Good at It, told a TED audience in Edinburgh in 2013 that “the harmful effects of stress on your health are not inevitable.” She points out that in many cases, stress can be a result of operating outside your comfort zone, and often accompanies breakthroughs in innovation, progress, or achievement. She laid out the results of studies suggesting that stress can provide better focus and clarity at work and with relationships when people deliberately create a mindset that embraces stress and centers on resilience.

Big business and commodification

Nor is mindfulness a panacea for all stress and anxiety. “There’s almost this implicit equation occurring that mindfulness equals wellness equals the solution for mental health problems,” says Patricia Arcari, Program Manager for Meditation and Mindfulness at the Zakim Center for Integrative Therapies at Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “That’s not always the case.” In an article in Psychology Today, San Diego-based psychologist Jason Linder contends that mindfulness has sometimes been over-hyped and commodified as it has become big business. He cites studies warning that over-promising mindfulness’ benefits can lead to disappointment and to people experiencing negative emotions. While beneficial for some trauma victims, other people who have suffered severe trauma discover that meditation and a focus on their feelings and emotions can instead trigger flashbacks and emotional distress.

Corporate mindfulness has drifted away from its Buddhist roots that emphasize sati as part of a deep philosophical journey toward becoming more aware of the causes of suffering and living a moral and correct life—precepts that don’t entirely sync with modern capitalism and employee mindfulness packages crafted by the likes of McKinsey and Deloitte. But this may not entirely matter if it provides succor to employees and their addled brains and helps them cope in the office—real and virtual—and with their families. One also wonders if at least some of the more spiritual side of sati might be creeping into secular mindfulness and into the workplace even as meditation becomes big business, expected to grow to a $9 billion market in 2027. After all, even the Dalai Lama has an app—not for meditating, but it’s loaded with his teachings on Buddhism and how to live a moral life.

Yet the ultimate test for mindfulness may be less about market sizes and how meditation increases the volume of the hippocampus and more about how it makes people feel—and whether they believe it works to reduce stress, particularly during the high anxiety of a pandemic that never seems to end. Camille Preston not only believes it does and has seen the positive influences on her clients and patients, but also that this will be a positive and lasting legacy of the pandemic era. “The last thing we want to do when this whole thing is over is to return to the bad old normal of stress and anxiety,” she says. “Hopefully this big experiment in mindfulness will end up being a pandemic silver lining for the future, for business, and for our kids.”