A new functional sparkling water from the founders of Fiji Water and Oatly claims to manage metabolic health by helping avoid blood sugar spikes after meals.

If you dial the toll-free line of Larkspur, California-based Good Idea, a company that makes a sparkling water energy drink that promises to curb blood sugar spikes, you might be startled to learn who’s picking up your call.

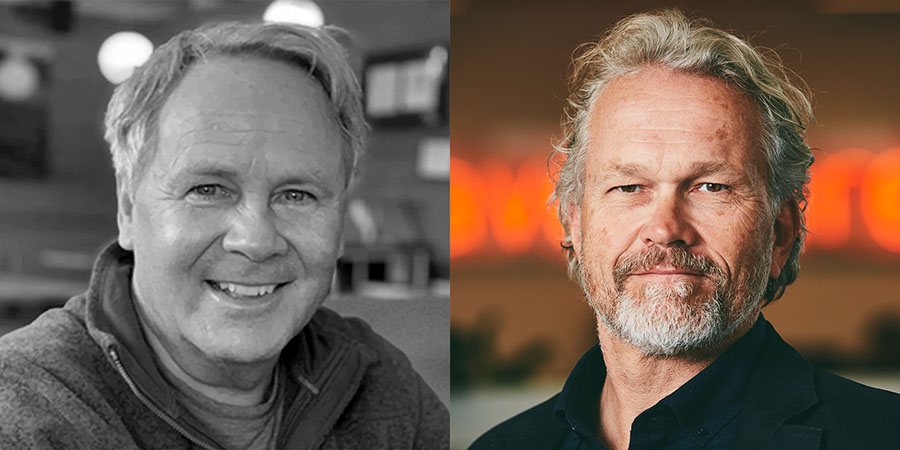

“I may speak to 300 or 400 people a week, or something like that,” says Doug Carlson, previously co-founder of Fiji Water, now CEO of Good Idea. “It’s literally one of my favorite parts of the job,” he says.

Odd as it may seem, part of the reason why Carlson is monitoring the toll-free line is that he’s an exuberant extrovert who loves a chat—and has plenty of great stories to tell—but also because his product is a bit unconventional. It’s not a sports drink or a nutritional supplement, but its effects have been tested in clinical trials, and it comes with instructions on how to use it. By talking to customers on the phone, Carlson can both educate them and gauge how much of that information is actually reaching them.

“We’ve done eleven clinical trials and published results on our website that basically show a 25 percent reduction in post-meal blood sugar,” says Carlson. Blood sugar typically spikes after a meal, as the stomach’s digestive juices liberate glucose from food and the intestines absorb it, causing insulin spikes in response, which can be problematic for people with diabetes and other conditions.

“The focus of our company is on the metabolic syndrome and the products are all related to managing metabolic health, which springs from managing your blood sugar,” he says. “The other thing that’s interesting is that if you don’t spike, you don’t crash, and that matters for everybody. If you’ve ever had an afternoon slump it’s because your blood sugar’s low. But if you can stay within the zone where you don’t spike and you don’t crash, you have a lot more energy.”

One in three U.S. adults

Metabolic syndrome is an umbrella term that refers to a constellation of metabolic problems, most notably type 2 diabetes, explains Thomas Barber, an endocrinologist at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom, “and more generally any impairments in blood glucose levels, either in the fasting state or after a meal, as well as abnormalities in cholesterol, raised blood pressure and waist circumference, which correlates with visceral fat,” he says. “It’s very common.” In the United States, about 1 in 3 adults have it, according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Good Idea waters come in beautifully designed 12oz cans, sold for about $3.25 each, and in five Scandi-inspired flavors—including sea berry and Swedish lemon. For the drink to work properly, one third of the can must be drunk before the meal, the rest with the food. “I’m finding that 60 to 70 percent, maybe a little more, of the people I talk to on the toll-free line are now aware to drink it just before and along with the meal,” says Carlson. To further reinforce that guidance, the recommendation will be more prominently printed on redesigned cans that are about to launch, and it also comes as part of a welcome email that people get when they buy the product online.

The challenge of properly communicating the drink’s correct usage and features will likely endure, which is one of the reasons why Good Idea is skirting retail almost entirely: “We’re not as focused on retail distribution, but on connecting directly to consumers and developing one to one relationships,” says Carlson. To do that, the company is sponsoring events like the U.S. Open of Pickleball—a combination of ping-pong, tennis, and badminton that is America’s fastest-growing sport—and has more lined up, including KetoCon in Austin and an American Diabetes Association event in San Jose: “I love going to those, because I get to talk to people who are very interested in this product,” Carlson says.

But according to Björn Öste, Good Idea’s Swedish co-founder, what would really help with customer awareness is… more competition. “I’ve traveled the world, I’ve been at conferences all over the place, I meet a lot of people and talk to a lot of people,” he says. “I don’t see anyone else doing what we’re doing—which is both good and bad, right?”

“I’d love to have three or four formidable competitors that do the same thing, but differently, because then we could truly achieve change in the world. It’s a little tough to be alone out there. Preaching, communicating,” Öste says. “We have to fight every day.”

“You don’t increase your total insulin load at all during the process, but you get a far better glucose curve.”

Competition has likely helped Öste’s previous venture, dairy alternative maker Oatly, which he founded in 1994 with his brother Rickard Öste, a nutrition expert and professor emeritus at Lund University in Sweden. The company raised $1.4 billion in a 2021 IPO when it was listed on the stock exchange, and they reported revenues in excess of $722 million in 2022. In 2008, the Öste brothers started Aventure AB, a biotech development company that they carved out of Oatly’s R&D department, and from which Good Idea was born.

“The challenge is that there [are] so many people out there, particularly in the various dietary supplements space, making unsubstantiated claims, making claims all over the map,” Öste continues. “And it’s doing everybody a major disservice, because it ultimately creates distrust. It’s impacting us too. So we feel like we have to run that extra mile every day. We are built on solid science and gold standard clinical trials, placebo-controlled, fully randomized, and double blind.”

How it works

The main ingredients in Good Idea are five essential amino acids, meant to “prime the metabolism,” the website says, and work in conjunction with a small amount of chromium, which is for “promoting insulin sensitivity.”

“The five amino acids are proven in our studies to trigger an early insulin release, and [when] imbued within a beverage, they are rapidly absorbed by the body. They kickstart the metabolic processing of the carbs that come with the food and turn into glucose. The result is that you don’t increase your total insulin load at all during the process, but you get a far better glucose curve,” says Öste.

Who is it for? “What we want to do is to reach a mass market,” says Öste. In the United States, 37 million people have diabetes, and almost 100 million have pre-diabetes, meaning their blood sugar levels are higher than normal, but not high enough to be diagnosed as type 2 diabetes. Most in this group are unaware of their condition. “How do you reach those who don’t know they’re pre-diabetic? One way is to develop a product that targets a broader consumer group, that delivers what everybody can recognize, general health benefits.”

He also has more specific categories in mind, including keto and paleo dieters, biohackers, students, and professional gamers: “eSports players get dramatically improved cognitive function from our beverage during the game, they perform better,” he says, hinting at data that is not yet published.

According to endocrinologist Thomas Barber, who is not involved with Good Idea and has reviewed the public information on their website, including two published clinical trials, “the presumption here is that in some way the amino acids are enhancing the release of insulin, but perhaps also impacting the absorption dynamics of the glucose and inhibiting a sharp rise post-meal. But we shouldn’t assume that it’s the direct effect of the amino acids that’s causing this insulin release—there could be other autonomic effects which we don’t fully understand currently.”

Other experts are less cautious and more direct in their criticism.

Short term responses

Robert Lustig, an endocrinologist at the University of California, San Francisco, and best-selling author of Fat Chance: Beating the Odds Against Sugar, Processed Food, Obesity and Disease, also looked at the published trials and considers that, within the context of pharmaceutical interventions, Good Idea may yet have more to prove. “I’m not impressed,” Lustig says, “The idea of coming up with something that would improve metabolic syndrome is a great one. But here are basically three problems.”

First, he says, both published clinical trials are looking at short-term responses only. “The fact that blood glucose is lower because of this drink is tantalizing, but doesn’t mean anything, certainly doesn’t mean that it’s good for you. There’s no information about what happens three months down the line, six months down the line. Is it still effective? Does it actually mitigate the negative aspects of metabolic syndrome?” Lustig asks.

Good Idea acknowledges the lack of such data and says they are currently designing longer-term studies.

Second, Lustig adds, the glucose is lower, but the insulin is higher, at least initially. “We do like to see a reduction in glucose, and they do have that. But there’s a second issue they’re not dealing with at all. In fact, they’re only making it worse, and that is the reduction in insulin. Turns out insulin is a bad player in the story of metabolic syndrome. The goal is not to increase the insulin. The goal is to lower it, by making the patient more insulin sensitive. They’re not doing that,” he says.

In response to this criticism, a Good Idea spokesperson says that “in our acute meal study, we did not observe a significantly increased area under the curve for insulin,” pointing to a graph that is also published on their website, and that “a pronounced first-phase insulin response compared to a late insulin increase could be beneficial.”

Third, Lustig points to the chromium, which is among the ingredients. “There are many animal studies that show that chromium has an effect on insulin sensitivity. That is true. But every human study that’s been done on chromium has shown no metabolic effect,” he says. Good Idea says they agree that “there is limited data from human studies,” and that “as a company aiming to improve health through smart foods, we are committed to obtaining further scientific data.”

Lastly, Lustig notes that while Good Idea positions itself as a treatment for metabolic syndrome, the trials have been done on healthy, albeit overweight, patients: “They haven’t tested it on metabolic syndrome yet,” he says. “I think they have released this prematurely.”

Good Idea responds that they are “not marketing Good Idea to treat metabolic syndrome or as a treatment, cure, or prevention against any other disease. We are a food that improves postprandial glucose balance, which is one piece of the puzzle in metabolic syndrome.” In an email exchange related to this discussion, Öste added that the company will be working on external clinical trials with patients with diabetes later this year, and that “diabetics should only consume our products after first consulting with their doctors.”

“For a first-year product, it’ll definitely be in the multi-millions, which is really good.”

At the moment, Good Idea is only available in the United States and Sweden, with more markets opening soon. The initial customer response, since launching in October 2022, has been great, according to Carlson: “We’re early in our first year, but the path is going in such a way that for a first-year product, it’ll definitely be in the multi-millions, which is really good. It doesn’t even compare to Fiji, which didn’t hit multi-millions until probably the third year,” he says, referring to the famous branded water company he co-founded.

We received a well-presented sample box containing all flavors for a taste test, done without a blood glucose monitor. Our experience was surprisingly nice. Billed as energy drinks, these cans didn’t give an artificially forced buzz the way most energy drinks do. They contain no caffeine or other stimulants, and their impact was far more subtle, taking the droopy edge off of an afternoon lull but without the uncalming effect of a chemical jolt. Is it possible to feel tired without feeling sleepy after hours and hours of hard work midway through a busy workday? That was what we experienced.

On the other hand, it’s a good thing these waters are billed as health drinks. The level of carbonation was ideal. The scent and color of the beverage was pleasing to the senses. And served cold, the initial bursts of flavors were bright, slightly sweet, and a perfect reward. But the waters have a strange aftertaste reminiscent of a diet soda, only more subtle and longer lasting. This slightly off-putting flavor lingers long after you’ve finished a can, though after drinking one can several days in a row, we did get used to it.

By far the best flavors were raspberry and lemon. The more unusual flavors like sea berry and strawberry elderflower may appeal to someone who has spent enough time in Northern Europe to be in thrall of hard-to-source Scandinavian fruits. But to the more uneducated palate, they just tasted nonspecifically fruity and unfamiliar.

Next up for Good Idea: more products. “We have four or five products at various stages of clinical trials right now,” says Öste. “Two of them are squarely targeting diabetics, and one is going to go into trials for women with gestational diabetes this spring. We have a breakfast product, we have more of a fruit juice or smoothie-type product, and there’s a soup too—what we work with is dictated by the nature of the raw materials and ingredients.”

Whether or not these products will also be called Good Idea remains to be seen, he says, but he reveals that the next launch will happen within a year—and the one after that, within another year. “We’re very excited about that, because we can see incredible opportunities to really have a meaningful impact and help people. And, of course, there’s a very strong commercial incentive,” he says, “but it feels good to do good.”