“I don’t like AI,” my mom yells from afar before we say hello. I’ve called to ask my parents about robots and a stickier subject—robot caregiving for later life. My mom is suspicious about allowing cold technology to take over warm, everyday tasks—convenience be damned. My dad is more optimistic, but he’s still a bit skeptical of how well a society that’s had its share of slip-ups will safely integrate robots.

Perched in their condo on the South Carolina coast, with many retiree neighbors, they have an up-close view of end-of-life uncertainties.

Artificial intelligence has brought robots a step nearer to the public consciousness as we question the myriad uses of machines that can deliver our food, drive our cars, and maybe even do our jobs.

“It’s gone from being a topic among technologists, to computer scientists, to being a topic among everyone,” says robot designer Carla Diana, the author of My Robot Gets Me: How Social Design Can Make New Products More Human. As people consider how data they generate feeds artificial intelligence algorithms, interest in the technology has snowballed.

I asked ChatGPT—what else?—what it would take to make robots palatable as caregivers. ChatGPT identified itself as a type of robot, but noted its limited caretaking capacity. It recommended instead human-like robots “so that they can establish a sense of trust and familiarity with the elderly people they are caring for.”

Many experts disagree.

Humanoid robots are generally difficult to design because of our myriad expectations for human behavior. When a robot has a mechanical appearance, like the box-on-wheels food delivery bots tested on college campuses, user demands are low. While we expect these machines to perform simple tasks accurately, we accept that their abilities are limited, says Eileen Roesler, a psychologist at the Technical University of Berlin. Their appearance makes this obvious.

An expert in human-robot interactions, Roesler points to an experiment in which a robot was designed with expressive eyes meant to establish the “trust and familiarity” ChatGPT parroted. It backfired.

“If you get an eyebrow in the wrong place, you can so easily communicate something that’s not intended.”

Those friendly eyes were “perceived more as sunny, nice, even kind of a toy,” she says. This can make even a highly precise machine seem unreliable and untrustworthy.

When a robot has a human appearance, we expect it to behave like a human, Roesler says. That means moving aside to make room for strangers in an elevator or directing its eyes toward a mess while cleaning it up. Creating robots that can respond to a myriad of these situations just as a human would be an insurmountable challenge for designers.

Finding affection in the uncanny valley

According to the uncanny valley hypothesis, a robot becomes more acceptable as it becomes more human-like. But at a certain point, a robot that is uncannily similar to a human, yet just slightly “not right,” arouses our suspicion, makes the robot seem creepy, and causes people to reject it. Even though we know the robot is not a human, our brains paint it with human expectations.

“Abstraction is our best resource” for avoiding these problems, Diana says. She once designed a robot whose expressive eyebrows had to be removed. It was too complicated to program natural eyebrow movements, and unexpected eyebrow movements unnerved users. “If you get an eyebrow in the wrong place, you can so easily communicate something that’s not intended,” Diana says. Getting these details right on humanoid robots, she adds, is a game of diminishing returns.

In some cases, a robot needs to mimic human behavior to complete its task. A robot barreling down a hallway in a straight line might be effective, but it won’t convert skeptics. So robots delivering medications through busy hospital hallways, Roesler says, should be programmed to move predictably around others and avoid collisions, just as people do. Particularly when robots will encounter strangers, such as delivery bots or housecleaners that might pass your neighbors on the sidewalk, it pays to incorporate a few human touches.

My parents, who are regulars at a few local eateries, find automated food delivery easier to fathom than homecare. “What if they’re delivering your pizza?” my dad quizzes my mom, who’s been skeptical so far.

“OK, now, food,” my mom says. “I’m willing to go with food.”

Adjusting attitudes toward technology

As for whether or not older adults would find robot caregivers acceptable, “that would likely depend on a variety of factors, including cultural attitudes toward technology, personal beliefs about the role of caregivers, and individual experiences with robots and other forms of technology,” ChatGPT responds.

I’m imagining the perks of a robot maid when Dad wonders aloud how much mobility you retain by doing your own chores, and whether it’s worth it to get some sort of robot maid. He’s right—preventing age-related muscle loss can boost both mobility and longevity.

“No machine can get it as clean as a human can,” my mom says. “Don’t ask me about a Roomba.”

Samuel Olatunji supervises human-robot interaction pilot projects as a robotics researcher at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, working with people who are encountering robot helpers for the first time. He’s not surprised that people like my parents are skeptical. “Movies, novels, and the media generally portray robots as perfect, as ready to take over the world,” he says. “When people get to experience the robots, in reality, the robots are not there.” Even a task like lifting a person and turning them in bed is still under development as scientists untangle our nuanced expectations for how robots behave. But robots can feed people, fetch items, and do chores like laundry. In other words, they are useful, but far from the independent-thinking caregivers that have inspired fearsome—if unrealistic—cinematic storylines. Maybe that’s a good thing.

Even experts find it hard to predict what robot behaviors people might like.

Like other researchers, Olatunji is adamant that robots are assistants that will free up staff in assisted living facilities to engage in more complex tasks with residents, not replace deeply needed face time. If a robot could dole out pills or help us put on our shoes, medical teams would have more time to engage in treatment plans, emotional health needs, or other complex topics and tasks.

Olatunji helps people acclimate to robots in pilot projects. He first shows people the space where they’ll meet the robot, then asks them to watch videos of the robot functioning properly. Next, research subjects observe a robot interacting with someone from a distance. Researchers assess whether the person seems willing to trust the machine before introducing the robot in person.

Fears, both real and imagined

“Did we not learn from this virus, COVID, how messed up people got from being shut away from their loved ones?” Mom says. She’s worried that home visits from a robot will stand in for needed human interaction.

“One of the biggest fears, especially in social human-robot interaction is that people like caregivers are not supported by robots, but are erased by the robotic counterpart, which is perfectly mirroring their own role,” Roesler says. Given the current technical restrictions of robots, “this is not really a realistic scenario.”

“People kind of underestimate how much psychology there is that goes into human-robot interaction,” says roboticist Alexis Block, UCLA postdoc and soon-to-be assistant professor at Case Western Reserve University. Even experts, she says, find it hard to predict what robot behaviors people might like.

A social boost, not a human substitute

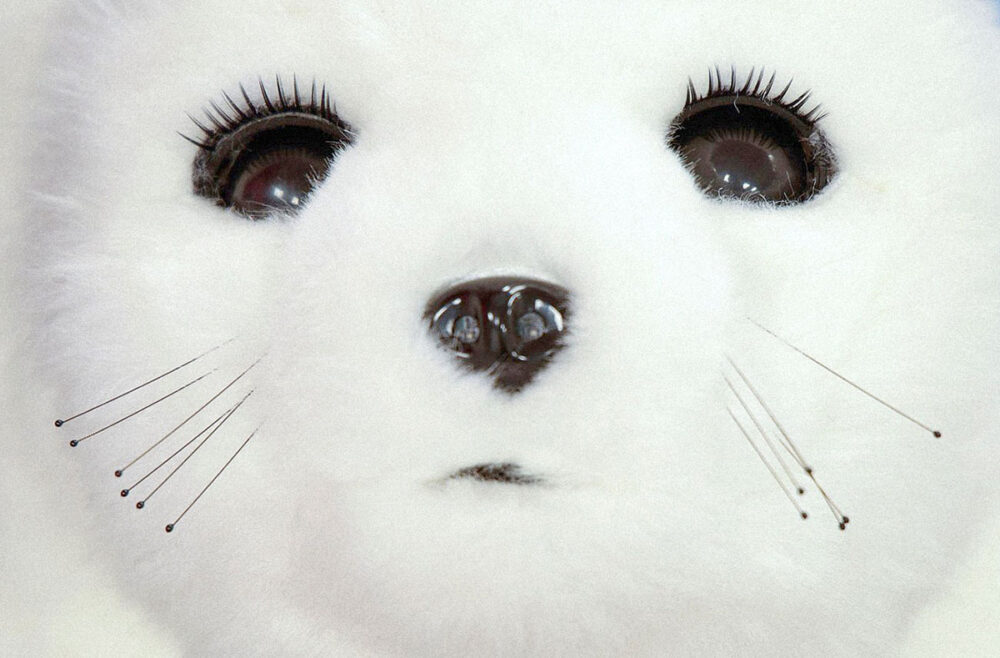

Social robots designed to hug us or interact have been available for years. Ever-popular Paro, a robotic harp seal pup first available in 2003, is now on its eighth iteration and available in Japan, Australia, the United States, Europe, and elsewhere. The stuffed robot nuzzles your hand and coos when petted. It can discern a smack, and can learn to avoid behaviors that provoke negative responses. Scientists say Paro is popular precisely because we’re not all that familiar with harp seal behavior. No one seems to mind that Paro sucks an oversized pacifier, which might seem strange in a more familiar cat or dog.

Paro’s 20 years of successful adoption, despite a $6,000 price tag, shows how impactful robots can be for people with dementia, Alzheimer’s, and even autism. Paro can simulate the benefits of animal therapy, and it is technically a biofeedback device. It can also simply be used as a companion.

Paro’s inventor, Takanori Shibata, says marketing can boost sales of robots and, seemingly, their acceptability, in the short term. But meeting expectations is key. “If the robots cannot satisfy the users, the sales will not continue long-term,” Shibata says. Still, a 2021 study of 55 hospitalized older adults with dementia or delirium found that 95 percent happily accepted the friendly seal.

When robots designed to offer social interaction start looking human, the reactions vary widely. A video of HuggieBot (below), a robot designed to provide positive, social touch through realistic hugs, shows a slightly human-like robot that offers hugs and provokes comments ranging from “aw, sweet” to “this is our sad future.”

“If they’re pushing back, we know that the person immediately wants to be released from a hug,” says Block, a roboticist who invented the HuggieBot as a grad student. Huggers also like the robot’s soft covering, slight warmth, and responsiveness. If a user pulls back against the robot’s arms or stops squeezing, it quickly releases them.

Surprisingly, Block says, people prefer semi-spontaneous rubs, pats, and squeezes during a hug with her robot. In early tests, she tried having HuggieBot roughly replicate the hug it received. “[People] didn’t like that. They said it didn’t feel natural,” Block says. She had imagined that spontaneous gestures would be frightening: “I’ve thought people would think the robot was malfunctioning,” she says. She was wrong. “People said that it made them feel like the robot cared about them,” she says with a smile.

Our demands for robots will be as unique as our individual health.

And in some care facilities, robots have already been well-received. In a Minnesota nursing home, Monarch Healthcare Management staffers incorporated semi-humanoid robots, including Pepper, for residents with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, as CBS Evening News reported last fall. The programmable robots told jokes, showed residents photos from their childhood, and could even recognize some changes in vital signs.

“I expect within the next five years we will see more robots being used to support everyday activities of older adults, either in their individual homes or in life plan community settings,” says Wendy Rogers, an expert in human-robot interaction and technology acceptance at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and an advisor to Hello Robot, a startup developing a complex robotic arm. She says our demands for robots will be as unique as our individual health and that robots could support anything from bathing and eating to medication management, grocery shopping, and transportation, to social engagement, as in the case of Paro. “Robots are being developed to support all of these activities,” she says.

Back in South Carolina, our conversation winds down, turning silly and speculative. My mom wonders if a robot might steal her jewelry. What if it’s programmed by a bad person? Do robots corrode and rust? “They should try their robots out here because saltwater ruins everything,” my dad says. And of course, they remind me, “Do your own dishes!”

An affordable robot for that can’t come soon enough.