Why We Loved “Orphan Black”

A thriller about cloning, gene editing, and bioengineering is the perfect show for our times.

You don’t usually see TV shows mention the supposed “fountain of youth” gene LIN28A, show nanopore sequencing, or use cloning as the backbone of the plot. That’s what makes Orphan Black so great.

The cult Canadian TV show just ended its five-year run, all the better for binge-watching it now. It had a relatively small viewership, but anyone who followed the series saw science fiction that was deeply grounded in science nonfiction. Its characters raised questions about the ethics of biotechnology that we already face or will face in the near future.

Science historian Cosima Herter helped create the show and is the namesake of one character, a scientist clone who’s investigating her own biology. Clone Cosima and the rest of the genetically identical characters (incredibly, all played by one actress, Tatiana Maslany) gradually uncover the ways other scientists at evil corporations have been exploiting them for shadowy experiments and personal gain. Those bad-guy scientists call themselves Neolutionists (no relation to proto.life!), and they describe their goal as “self-directed evolution.”

Flawed clones

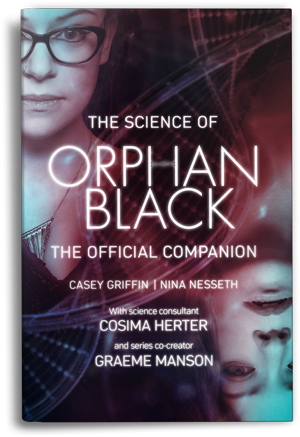

One of the Neolutionists’ main methods is cloning. Though the show is set in the present, scientifically Orphan Black takes place in “a bit of an alternate timeline,” says Nina Nesseth. She and Casey Griffin, a developmental biology graduate student at the University of Southern California, wrote the new book The Science of Orphan Black: The Official Companion.

In the show’s universe, scientists successfully (and secretly) created human clones in the 1980s. But in the real world, the famous cloned sheep named Dolly wasn’t born until 1996. Since then, researchers have successfully cloned human embryos, but haven’t let them develop further. Human reproductive cloning is banned in more than 40 countries. It’s not a federal crime in the United States, but it’s banned in some states.

Cloning humans and other primates is technically difficult. One of the main things that goes wrong is that the cloning process messes with “spindle proteins” that help cells divide. Orphan Black was smart enough to take this subject on. In the second season, one of the cloning masterminds says his wife “solved the spindle protein problem.”

Even if scientists surmount such difficulties in the real world, a 2017 Gallup poll found that 83 percent of U.S. adults think it would be morally wrong to clone a human. And the clones on Orphan Black are indeed unhappy to learn that they’re part of an experiment they didn’t consent to. The show, Nesseth says, forces us to ask: Could a clone’s creator claim ownership of that person? Could a clone, or a clone’s DNA, be patented? What unexpected problems might arise in a clone? In the show, nearly all of them are dying of a mysterious genetic disease.

“I think the show highlights basically all of the main reasons why it would just not be good” to clone humans, Griffin adds.

A Genetic Algorithm Revealed My Possible Babies

“This stuff is cool”

The illness slowly killing off the Orphan Black clones is an accidental side effect of the genome tweaks that the Neolutionists engineered to make the clones sterile. By the show’s present day, these scientists have moved on from cloning and are using other types of gene editing to change people’s evolutionary fates. In a sinister assisted-reproduction facility, they engineer ideal babies (or deformed ones). Another technology delivers gene therapy to adults via not-so-realistic cyborg maggots. (Orphan Black didn’t invent that plot device. The cyborg bug meme crops up a lot, from TV’s Black Mirror to Star Wars: Episode II—Attack of the Clones.)

Spoiler alert: one Neolutionist is fiddling with a particular gene to try to live longer. It’s LIN28A, which in reality has some fountain-of-youth properties. It’s normally active only in embryos; the protein it makes the body produce appears to work wonders for tissue repair. But as Griffin points out, engineering this gene to be active in an adult would be unlikely to make the Neolutionists live longer. Longevity is “not as simple as one gene,” she says.

And no matter how much future parents manipulate their children’s genomes, they won’t be able to control who those children mate with. The progeny of people with edited genomes will probably regress to the mean and not start a race of superhumans, says University of Alabama at Birmingham bioethicist Gregory Pence, who also wrote a book about Orphan Black, called What We Talk About When We Talk About Clone Club. That means the Neolutionists on Orphan Black probably wouldn’t succeed in their goal of trying to control human evolution.

They also aren’t very good scientists, say Nesseth and Griffin. A better model is Cosima, the scientist clone. Her curiosity drives her to pursue the same questions as the Neolutionists, but “with the goal of helping people, and giving people options,” Griffin says. “Cosima just thinks this stuff is cool.”