This tech could boost fertility and fine-tune hormone levels.

In a handful of laboratories around the world, researchers are working on a radical new fertility option for women: an artificial ovary.

The idea is that by beginning with just a tiny piece of tissue, scientists could grow a whole new organ and then implant it to replace an ovary that’s faulty. Or they could give an ovary to someone who wasn’t born with one and takes hormones instead—say, a transgender woman. It could also become an alternative way of delivering hormones for menopausal women and others who take hormones. It might even reverse menopause.

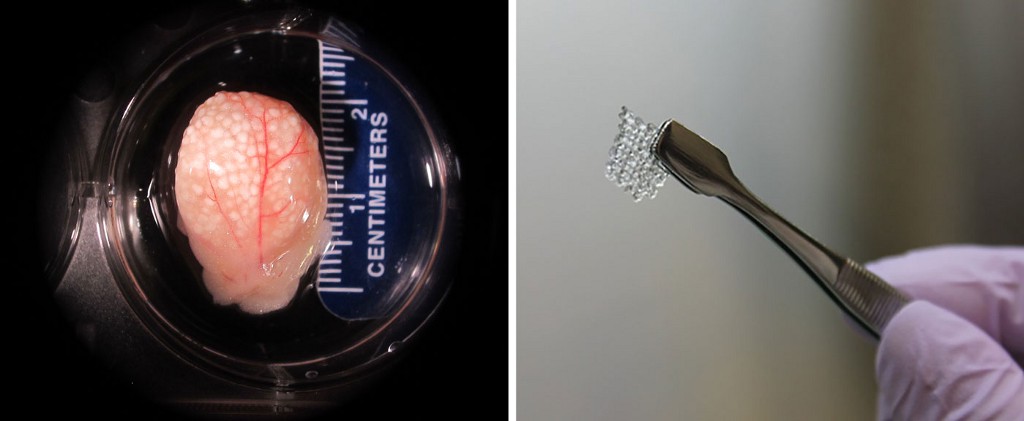

Until recently, artificial ovaries had been implanted and tested only in animals, using animal tissue. But a major step forward came in July, when researchers in Copenhagen used human ovarian tissue to construct an artificial ovary that survived when implanted in mice.

Susanne Pors and her team used a chemical solution to strip cells out of the ovarian tissue, leaving behind a “scaffold” of proteins and collagen. Then they seeded the scaffold with hundreds of human follicles, the fluid-filled sacs that contain immature eggs.

Another breakthrough came last year, when reproductive scientists at Northwestern University reported that they had created a fully functioning mouse ovary with a special 3-D printer. They used gelatin as the “ink” and printed a scaffold, which they filled with mouse follicles. When they implanted it into a mouse that was infertile from having an ovary removed, the mouse was able to ovulate and had healthy pups after mating with a male mouse. The artificial ovary boosted levels of important hormones, too.

Getting an artificial ovary to function for years will be the biggest challenge. In the recent work in Copenhagen, only a quarter of the follicles survived at least three weeks. The artificial ovary printed at Northwestern functioned for 40 days.

Nonetheless, scientists already see ways to make artificial ovaries last much longer, and fully functioning ones could be ready for women in a decade or so. Which means it’s not too early to think about all the ways it could be used.

Making the transition

The artificial ovary was initially thought of as a way to improve the practice of freezing ovarian tissue, an option for girls and women who need to undergo cancer treatments that could render them infertile. Years later, that tissue can be implanted back in women when they’re ready to have a child. But that procedure comes with a risk of transplanting tissue that still contains some cancer cells.

“If you had an artificial ovary, you could avoid that risk,” says Sandra Carson, who is vice president of education at the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and whose former lab at Brown University created the first artificial ovary, reported in 2010. It was made with human tissue but never implanted.

Soon other researchers, like Teresa Woodruff, a reproductive scientist at Northwestern, became interested in trying to construct one. Initially, her focus was on female cancer patients, but now she sees it as a potential option for transgender women. An artificial ovary could be inserted just below their skin, in a minimally invasive procedure, perhaps under the arm or in the fat tissue of the stomach.

Why would these women do it? One reason is that it would be a longer-lasting way to deliver hormones. But scientists also think the hormones produced by an artificial ovary would be safer and better tolerated by the body than the synthetic ones used in hormone therapy. Pills, patches, and injections that deliver estrogen, the main hormone that promotes the development of female characteristics, have been shown to increase the risk of health problems like blood clots and liver damage.

Even more futuristic is an artificial ovary that actually releases eggs. Those eggs could be harvested from the ovary and fertilized in vitro, allowing a transgender woman to have a child using a surrogate. Eventually, an artificial ovary and a uterus transplant might allow a transgender woman to conceive and carry a child to term.

Fertility boost

An artificial ovary that produces eggs could help women with fertility problems that originate in the ovary such as polycystic ovary syndrome, which affects nearly one in 10 women. PCOS is caused by elevated levels of a hormone called androgen. Many women with PCOS have trouble getting pregnant, and some never release eggs at all.

Women with premature ovarian failure, or primary ovarian insufficiency, could also benefit.

In women with this condition, the ovaries stop working before age 40, bringing on infertility and menopausal symptoms. In both cases, women could have an ovary removed and an artificial one implanted in place.

An artificial ovary could extend a woman’s fertility, too, so she could wait until later in life to have a child. “You could theoretically prolong the life of an ovary beyond menopause,” Carson says.

Replacing hormone replacement

Emmanuel Opara, a professor at Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, thinks an artificial ovary could be good for post-menopausal women even if they don’t want to have children at that stage in life.

As with transgender women, the hormones produced by the artificial ovary could be safer and more effective than synthetic versions. Many women turn to hormone replacement therapy, or HRT, when they hit menopause, as their ovaries become smaller and release fewer hormones like estrogen and progesterone. This can cause hot flashes, vaginal dryness, sleep problems, weight gain and, worse, bone deterioration. But HRT isn’t recommended for long-term use because it appears to increase the risk of stroke, blood clots, heart attack, and breast and ovarian cancer.

What if a 75-year-old woman would want an artificial ovary to have a child?

Opara and his colleagues have engineered rat ovaries by isolating two major types of cells found in the ovaries — granulosa and theca cells — and growing them into three-dimensional balls of tissue. They implanted the ovaries into the rats’ fat tissue right below the skin covering the abdomen. A week later, the artificial organs started producing estrogen, progesterone, and two other hormones not used in hormone replacement therapy. The animals with artificial ovaries had less body fat and better bone health than ones that were given synthetic hormones.

This artificial ovary was able to produce hormones that fluctuated for three months. Opara says that suggests a lab-made ovary could produce levels of hormones that match what the body needs — an advantage over HRT.

Unanswered questions

Before an artificial ovary becomes a reality, it will need to be tested in larger animals make sure it’s safe and long-lasting. Monica Laronda, a reproductive endocrinologist and Woodruff’s collaborator at Northwestern University, is planning to test her team’s 3D-printed ovary in pigs next. The group also thinks it can begin to ramp up the amount of time that an artificial ovary can function. The trick will be to seed it with greater numbers of immature follicles, some of which will stay dormant even while others grow into mature eggs earlier. Laronda and her team have found that the structure of the artificial ovary is directly linked to whether or not the follicles will survive in the ovary.

Even so, there are big questions to resolve, says Cynthia Stuenkel, a clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego, and a spokeswoman for the Endocrine Society. She says the idea of an artificial ovary is exciting but worries about the possibility of hormones bringing periods back in menopausal women. “Women usually don’t mind after menopause that they’re not having their monthly menstrual cycles,” she says.

Another issue is that donor tissue would be required to make artificial ovaries for transgender women or those who don’t have healthy ovarian tissue. There’s always a chance that the recipient’s body would reject it.

Eventually, an artificial ovary and a uterus transplant might allow a transgender woman to conceive and carry a child to term.

There’s also the question of whether there would be an age limit to getting an artificial ovary that can produce eggs. For instance, Opara wonders: What if a 75-year-old woman would want an artificial ovary to have a child? Many fertility clinics have an age limit of 45 to 50 for in-vitro fertilization, out of concerns for pregnancy complications as women get older. There’s also the notion, imposed by some fertility doctors, that a woman or her partner should have enough lifespan left to be able to care for a child.

First things first, though. The most immediate use of artificial ovaries will be to test fertility treatments and other drugs in the lab, before women get them, to make sure they’re safe. And the first people to get artificial ovaries implanted will likely be cancer patients. “For pediatric patients, we’re not just talking about fertility but we also want to restore the endocrine system, which is responsible for healthy development,” Woodruff says. “It really is an unmet need.”