10% of women suffer from this painful condition, which often goes undiagnosed for years. This has to change.

I was confident the first time I told my doctor what I had. A freshman in high school, I had fainted from catastrophic pelvic pain in the middle of my ninth-grade Earth science final, went to the nurse’s office, sat there while they took my vitals, answered the nurse’s questions, and then finished my test. I handed in my tear-soaked scantron answer sheet, went home, and scoured the internet. Soon I began to convince myself what happened. I had endometriosis—a progressive systemic inflammatory disorder defined by the presence of endometrial-like tissue, or lesions, outside the uterus. Having a period was relatively new to me and I knew cramps were supposed to hurt, but… that much?

“Yes, that much” my doctor answered after I’d confessed my experience to her. I handed her a printout of the WebMD page for endometriosis, where I’d carefully flagged my symptoms with yellow highlighter: chronic pelvic pain, severe period cramps, painful bowel movements, debilitating fatigue, random hot flashes, and fainting spells. She seemed unworried—even dismissive.

“You’re just 15,” she smiled. “You’re too young to have hot flashes.” She flipped the WebMD handout over on her desk, and without reading it but with a knowing look on her face, she drew a great big bell curve on the back. “Most girls who have period cramps are here” she explained, circling the center of the graph for emphasis. “Some girls have it worse,” she shrugged, pausing to let those words sink in. “It just so happens that you are here” she said, circling the far right tail of the graph. Then with a furrowed brow, she offered her sympathy, handed the printout back to me, suggested I take four Advil if I needed to, and sent me on my way. I left, still clutching the paper with the great big bell curve and the little circle that was supposed to be me.

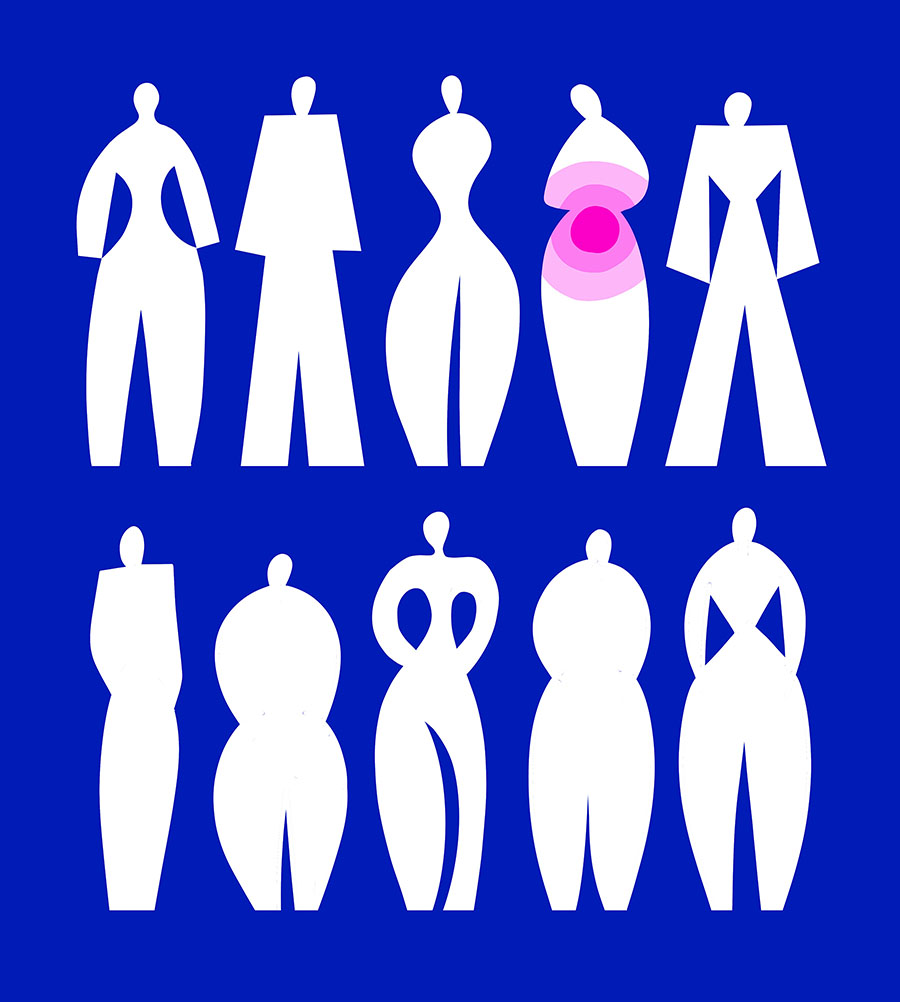

Still, I felt unconvinced. But by the time I was finally diagnosed with endometriosis years later, I had seen six ob-gyns, visited the emergency room nearly a dozen times, and had been hospitalized twice. After nearly a decade of fighting for a definitive diagnosis, my confidence was shot, and my stamina was dwindling. And although I had spent years feeling starkly alone in this experience, I’d soon learn I wasn’t. In fact, I was among 1 in 10 women.

The missed disease

Endometriosis is a public health crisis. It impacts at least 10 percent of girls and women around the world, as well as trans and nonbinary individuals, affecting 6.5 million people in the United States alone. It can cause chronic, life-disrupting pain, fatigue, dysmenorrhea (painful periods), dyspareunia (pain during sex), and accounts for 1 in 10 of all cases of infertility. Currently there is no known cause or cure, and available treatment is restricted to two methods of surgery and a handful of limited hormonal therapies. Like many chronic, progressive diseases, experts say that early detection and treatment is critical for better health outcomes of endometriosis—as well as for improving your quality of life. Unfortunately, early detection is rarely the case. In fact, in the United States people have to suffer through an average of 8–11 years of symptoms before finally receiving an accurate diagnosis. I myself had to wait eight long years, relatively fast by those standards.

Notoriously hard to diagnose, endometriosis has been called “the missed disease” by researchers, experts, and patients alike. Timely diagnosis is difficult to achieve as the disease pathology usually can only be properly visualized and diagnosed through exploratory laparoscopic surgery. Although imaging techniques like transvaginal ultrasounds and MRIs can sometimes indicate the presence of endometriosis-like structures, a negative scan does not rule out the possibility of endometriosis. Although there are some emerging technologies and scientific discovery in this area, further investment and research is necessary to develop an effective non-invasive way to test people.

Another complication is that the symptoms of endometriosis squarely overlap with other gynecological, gastrointestinal, and neurological conditions. Doctors are often inclined to explore other explanations first.

Time to diagnosis is further delayed by the gender pain gap, a phenomenon in which women’s pain is taken less seriously than men’s pain. Studies show that women’s complaints of pain are perceived to be emotionally driven, often resulting in referrals for psychological support whereas men’s complaints of pain are met with more thorough medical investigation and follow-up. This gender bias poses a serious threat to endometriosis patients. It normalizes women’s pain, perpetuates disease stigma, and often results in misdiagnosis, which prevents people from getting necessary and timely care. Plus, it’s infuriating.

According to a 2020 study of 748 women with endometriosis, 78 percent of them reported being misdiagnosed with a different physical illness initially, and nearly half reported being misdiagnosed with a mental health problem before eventually being correctly diagnosed. On behalf of all of them, I say: No, this is not in our minds!

For a progressive disease, diagnostic delays are dangerous. People with later-stage endometriosis often experience more severe tissue damage and scarring around affected areas. As a result, they require more intense treatment and suffer from worse long-term health outcomes on average.

Endometriosis is estimated to cost the U.S. economy $22 billion annually and the global economy $70 billion.

At the societal level, the implications are profound. Endometriosis is estimated to cost the U.S. economy $22 billion annually and the global economy $70 billion. Direct and indirect medical costs, like hospitalizations, work-related absenteeism, and short- and long-term disability contribute to its rising burden on our society. Diagnostic delays and a lack of effective, non-invasive medical therapies lead to thousands of gynecologic hospitalizations and surgeries each year. In the United States alone, endometriosis is the second most common reason for hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus), accounting for more than 400,000 hysterectomies each year. And yet, sadly, even a hysterectomy or an oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) is not a cure, as both can leave surrounding disease areas behind, leading to the persistence of painful symptoms.

And for all the systemic implications of the many missed or delayed diagnoses, perhaps even more profound are the deeply personal ones. Almost every single symptomatic person who reaches the later stages of endometriosis and finally gets a diagnosis has already suffered for years with terrible pain. I should know because I am one of them.

Thinking outside the uterus

Endometrial tissue is a normal type of tissue found in the innermost lining of the uterus. During reproductive years, this tissue responds to monthly hormonal triggers by thickening, and in the absence of pregnancy, it sheds. The menstrual bleeding that results has historically been stigmatized—so much so that a 2016 study in 190 countries surveyed found there are more than 5,000 current slang terms for a woman’s period, often negative.

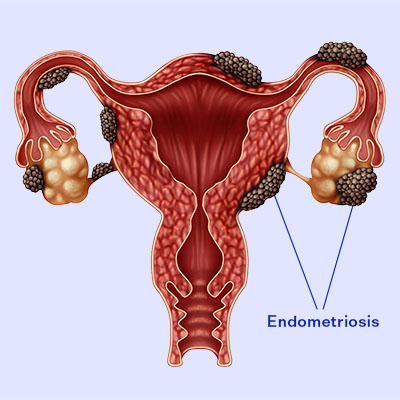

For those of us who suffer endometriosis, this underlying menstrual stigma makes the lack of understanding of the disease worse. In endometriosis, a similar but different endometrial-like tissue is found in areas outside of the uterus, usually within the pelvis. This endometrial-like tissue makes and releases its own estrogen and on its own independent schedule, also causes bleeding and inflammation. Unlike inside the endometrial cavity, however, bleeding in other areas of the pelvis has no way of leaving the body and ends up irritating surrounding tissues, creating pathologies like scar tissue, adhesions, and nodules—and above all else, pain.

Although the disease was ranked on this year’s U.S. News and World Report of the 10 most painful medical conditions (sandwiched between severe sickle cell disease and breakthrough bone cancer pain), endometriotic pain is often minimized by doctors, family, and society at-large as nothing more than “a bad period.” But the irony of endometriosis is that even though such severe, debilitating, and life-impacting pain is one of its classic hallmarks, because of its association with normal menstruation, that pain is all too often “normalized” and dismissed.

Currently, most physicians recommend and prescribe regularly using over-the-counter NSAID drugs like Advil or Aleve to manage painful symptoms. For moderate-to-severe cases, however, NSAIDs aren’t only ineffective, but their chronic use can give rise to other health issues like stomach ulcers or bleeding, liver disease, and kidney damage. Linda Griffith, who founded the MIT Center for Gynepathology Research in 2006 and also suffers from endometriosis, reports having taken up to 50 Advil on one single day of her period just to survive the pain. If that sounds extreme, it’s because it is. But so is the pain.

On Twitter, I stumbled across the profile of someone named Claire, who once described how her endometriosis feels “like my uterus is sitting on a bed of razor blades.” On a Reddit thread I read devoted to the disease called r/endo, someone who goes by the moniker “KnittedOwl” confides, “[it’s] like knives going in and twisting. Other times it’s like barbed wire is being wrapped and twisted across my abdomen.”

But by far the greatest impact of the underlying menstrual stigma linked to endometriosis is that people who suffer from the disease cannot count on receiving adequate and timely medical attention. Despite how common and severe it is, endometriosis is still not well known. Experts struggle to reach a consensus on its cause, definition, and treatment, resulting in confusing information and stagnant, ineffective care.

Stuck in the 20th century

Depending on its severity, endometriosis requires different types of care. Most people (around 80 percent) have what’s called superficial peritoneal endometriosis, in which the aberrant tissue is found on the peritoneum, the membrane that lines the abdominal cavity. But some people can also have ovarian endometriosis, where blood-filled sacs, called “chocolate cysts” because of their color, form on their ovaries. Other people suffer deeply infiltrating endometriosis, where the disease becomes embedded deeply within other organs like the bladder and bowels. In some rare cases, endometriosis has been found in the heart, lungs, and brain.

Under current care standards, while the symptoms of someone with stage 1 peritoneal endometriosis could be managed with birth control, a person with deeply infiltrating endometriosis would likely require several complex surgeries. It’s also worth noting that “severity” is usually determined using the 25-year-old ASMR staging system, which is based on visual presentation of lesions during laparoscopy. But this staging system often correlates poorly with patient reports of pain, and it lacks the precision of more modern 21st century quantitative image-based or molecular biomarkers we see with other diseases. This is important because disease staging not only helps to categorize anatomical effects and damage, but it guides treatment and informs your prognosis.

With endometriosis, we seem to be stuck in the 20th century. I didn’t know I had stage 4 deeply infiltrating endometriosis until early 2022, when a surgical specialist was able to diagnose and treat me during a robot-assisted laparoscopy. In fact, after my first endometriosis surgery in 2019, I had hoped that the pain would feel more manageable for several years, if not forever.

So when my symptoms not only returned, but worsened just six months later, I once again felt alone and confused. If the surgery was supposed to help, why was this still happening to me?

What we don’t know CAN hurt us

When I returned to the internet for answers, I was shocked by what I found: Glaring inconsistencies in how even the most credible sources define the disease, its cause, and recommended treatments.

Although there is no known cause for endometriosis, it was once believed to be the result of retrograde menstruation. According to Sampson’s Theory of Retrograde Menstruation, which New York pathologist John Sampson first proposed in 1927, endometriosis occurs as the result of endometrial tissue cells escaping during menstruation and flowing backwards, depositing themselves into the abdominal cavity and growing into endometrial tissue upon any organ “favorable to its existence.”

While Sampson’s work was essential in advancing endometriosis research, some experts today worry that it doesn’t hold up to more modern and robust research. “Retrograde flow is common, occurring in most people who menstruate, so this theory wouldn’t explain why just 1 in 10 menstruators would develop endometriosis,” says Ken Sinervo, the medical director at the Center for Endometriosis Care, a surgical practice based in Atlanta, Georgia. The theory of retrograde menstruation is further challenged by research showing critical histological differences between the type of tissue found in the endometrium and that found in endometriosis lesions. Because endometriosis has been found in organs far from the pelvis and even in neonates and cisgender men, retrograde flow cannot explain all cases of the disease.

Yet Sampson’s theory continues to be the most widely accepted as the cause of endometriosis, which can be harmful, some experts say. According to Sinervo, there are other pathways that researchers should be exploring, like genetics or stem cells. “Endometriosis is a complex systemic disease that, without question, involves multiple factors and pathways beyond retrograde menstruation,” Sinervo says.

Tamer Seckin, the founder of the Endometriosis Foundation of America, disagrees. On a recent Facebook Live Q & A, Seckin compared people who question the prevailing theories of endometriosis to flat-earthers. “Endometriosis is a disease of periods, of menstruation,” he said. “That’s it. It’s associated with menstruation.”

“Patient-centered care focuses on the diverse systemic effects of the disease, not just on the reproductive system.”

Seckin’s views towards retrograde menstruation are strong, and I reached out to his team to request his comments on other theories. Dan Martin, their scientific and medical director spoke to me hours before we went to press and clarified the foundation’s stance. ”Endometriosis is a systemic disease,” he says. “All cells of origin theories have similar problems, they don’t explain how [the disease] gets everywhere, they don’t explain why it’s been found in cis men.

But the bigger question, he says, is not where the cells come from, but why they lead to endometriosis. “We need to focus on early detection and less invasive treatments. If you can get it early enough, there’s a chance you can still do something about it,” Martin says.

According to Katie Boyce, an Arizona-based professional advocate for endometriosis patients and cofounder of the Endo Girls blog, “A huge part of the problem is that ob-gyns are the primary point of care for endometriosis patients, and they have a lot on their plates. Obstetrics and gynecology were squeezed into one specialty in 1994 which limits the capacity of ob-gyns to become experts about this complex, multifactorial, systemic disease.”

Katie touches on a key point in the battle to improve endometriosis care—ob-gyns aren’t intentionally glazing over endometriosis. More likely, the inadequate care experienced by patients is the result of confusing information systems, outdated clinical guidelines, and a historical lack of federal investment. Despite good intentions, however, the current standards of endometriosis care that are practiced by most gynecologists are not only inadequate in treating the root cause of the disease, but pose serious risks to patient health.

Chemical castration and misinformed consent

People with endometriosis are often prescribed some form of supplemental hormonal therapy to help with pain management and slow the disease. These hormonal treatments include oral contraceptives, GnRH analogs, progestin therapies, and aromatase inhibitors, and they sometimes do work to reduce painful symptoms. However, they’re not a sustainable solution, as they only work while you’re taking them, and symptoms return once the medication is discontinued. And for people who experience severe side effects (which is not uncommon with hormonal medication), or for those trying to get pregnant, these medications are not an option.

Some of these medications are controversial. The class of hormone-modulating drugs known as GnRH agonists and antagonists that can artificially induce menopause as quickly as overnight have been widely criticized for causing intense side effects and have been associated with irreversible health damage such as loss of ovarian function, loss of bone density, and loss of memory for many people.

In 2020, my own doctor recommended Lupron Depot, a commonly prescribed GnRH antagonist for moderate-to-severe endometriosis cases. During the 15-minute post-op visit in which she diagnosed me with the disease for the first time, she also offered to administer the menopause-inducing dose. At the time I almost agreed. I was desperate to feel better. I’m so grateful I didn’t.

Even when used with protective hormonal add-back therapy, Lupron is aggressive. It is also used to treat advanced prostate cancer and is not recommended to be used for more than 12 months in a lifetime. With more than 25,000 adverse event reports to the FDA, Lupron has been the subject of controversy among patients who’ve experienced severe side effects like suicidal thoughts, permanent loss of fertility, and severe joint pain as a result of the drug. Still, sales of the drug are expected to grow by over $1 billion from 2021–2026, with almost half of the growth originating from North America alone.

Although hormonal suppression therapies do not treat endometriosis and are limited in their ability to successfully support pain-management efforts, most patients are not aware of alternative treatments such as excision surgery, physical therapy, and lifestyle/diet changes. “It really gives rise to this idea of misinformed consent, where you have patients undergoing intense treatments without really being fully told how harmful they can be, or what their other options are,” says Sinervo.

His stance is echoed by other experts and thought leaders and several patient-driven sources have noted the need for increased referrals to endometriosis specialists by ob-gyns. Boyce from the Endo Girls blog agrees. “We need ob-gyns to refer patients to specialists, people who are highly skilled and trained to provide robust, up-to-date treatments. Patient-centered care focuses on the diverse systemic effects of the disease, not just on the reproductive system. Competent care involves an endometriosis specialist, and usually a multidisciplinary medical team as well.”

But adequate care is not easy to access. According to the Endometriosis Foundation of America, of the 40,000 ob-gyns in the United States, just 150 are skilled in delivering up-to-date treatments, such as non-hormonal treatment options and excision surgery.

The hidden gold standard

Currently considered the gold standard for treating most endometriosis cases, excision surgery is the only way for doctors to remove lesions from affected organs at their root, minimizing the risk of the disease coming back and reducing the burden of long-term symptoms and pain. It offers a rare beacon of hope for affected individuals. But even though leading experts, surgeons, and advocates recommend it, there’s a huge catch: most people don’t even know about it. And many who do can’t access it.

A competing procedure, known as ablation surgery, is more routinely performed by gynecologists. It is a much simpler (though less effective) surgery that involves burning away the superficial surfaces of the diseased tissues. Ablations take about 30 minutes and can be done by most gynecologists in outpatient settings. I had one during my winter break in late 2019. I had come home from grad school, and the next morning my mom drove me to the hospital where my surgery was completed in about half an hour. I was back home before dinner, and back on my feet by the end of the week. Though the ablation process was faster, my pain returned just several months later, and it became clear that the issue was still unresolved.

A four-hour excision surgery would be reimbursed at the same rate of a much easier and cheaper 40 minute ablation surgery—even if the latter is less effective.

Excision surgeries are much more involved. They require additional surgical skill and can take four hours or more under general anesthesia. When I had mine done a few months ago, the process wasn’t as easy. Rather than driving to my local hospital, my family and I flew from New York to Arizona to access care from an expert at the Phoenix Mayo Clinic. Although traveling for care was an added strain to my recovery process, it was my best option.

But the American College of Gynecology’s website does not currently even recognize excision surgery as a treatment option. Neither do most insurance companies. This is because insurers often base their decisions about billing and reimbursements on Medicare billing codes, and currently there is only one billing code for all methods of endometriosis surgery. That means a four-hour excision surgery would be reimbursed at the same rate of a much easier and cheaper 40 minute ablation surgery—even if the latter is less effective.

That creates a perverse incentive that maintains the status quo. For the average ob-gyn, there is little financial motivation to offer excision surgeries if it is not adequately reimbursed.

Furthermore, the lack of separate coding forces the few experts who are skilled in excision to be out-of-network, causing many people to fall into a “care gap,” where they struggle with insurers to receive reimbursements for astronomical, but necessary medical costs. They’re usually left with huge medical bills, incomplete treatment, or both.

Time to pull back that curtain

Although endometriosis is a disease riddled with controversy and discord, there is one thing that almost all stakeholders agree on: the need for organization, advocacy, and policy change. Historically, endometriosis has suffered from a profound lack of federal investment and funding. In 2018, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) cut endometriosis disease funding down to 6 million dollars (which equals roughly $1 per patient). Endometriosis had fallen among the least-funded diseases by the NIH, ranking at 276 out of the 288 included diseases.

In the face of institutional inaction, patients have filled critical gaps by using social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, Reddit, and blogs to form communities, share patient-centered disease information, and organize advocacy efforts. These communities are critical in increasing awareness and empowering patients to make more informed decisions about their health.

It’s the sort of community that Abby Finkenauer, a former congresswoman from Iowa, was looking for when she was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. “When I got to Congress in 2018, I sought to join the Endometriosis Caucus, only to learn that no such caucus existed. That was shocking. There’s a caucus for everything in Congress—from the Fragrance Caucus to the Rock Caucus—but there wasn’t an organization advocating for greater research and funding into this serious and widely misunderstood disease.”

This is partially what pushed Finkenauer to lead an unprecedented effort to create the first Bipartisan Endometriosis Caucus in the House of Representatives and double the federal funding for endometriosis research. “I have struggled with endometriosis, and the lack of research, funding, and awareness led to unnecessary pain and procedures in my own life. That’s the story that millions of Americans face because of the glaring gap in attention and advocacy on this serious condition that affects 1 in 10 women.”

Like other advocates, Finkenauer points out the vitality of political organization and action to effect change. “We need more common sense leadership that can get important, substantive things done that actually help people, including continued bipartisan federal investment in endometriosis research,” she says.

Federal investment is undoubtedly important. Decades of political inaction had allowed endometriosis to become a hidden health crisis, tucked away behind curtains of stigma and confusion. In reality, endometriosis is hidden in plain sight, woven into the daily lives of hundreds of millions of people. The time to pull back that curtain is now. Ten percent of women should not fall on the wrong end of the bell curve. With improved advocacy, increased federal investment, and a greater uptake of patient-centered priorities in developing treatments and guidelines, there are pathways for better care.