This biotech CEO wants to slow women’s aging by extending ovulation.

Last June, Daisy Robinton addressed the new graduates of UCLA’s molecular, cell, and developmental biology program from home via Zoom. Long blond hair swept to one side, smile wide, sunny, and luminous through the screen, she exuded warmth even as she shared the serious lessons of her journey from walking in their shoes as a UCLA biology student to obtaining her PhD at Harvard to becoming a biopharma startup CEO. Then, still smiling, she paused her own story and dropped on the young graduates a question that could drive their careers.

“What are you furious about?” she asked.

Robinton herself is furious about the fact that science and medicine have spent decades mostly ignoring more than half of the population: women. Medical history is littered with examples of women suffering ill effects of drugs—such as the antihistamine Seldane, which caused dangerous heart arrhythmias, disproportionately in women—that weren’t adequately tested on them because most clinical trials were filled primarily with men. The National Institutes of Health didn’t start requiring clinical trials to enroll women until 1993 or animal studies to include females until 2016. As recently as 2020, Robinton heard a lead researcher working on a COVID-19 treatment suggest that they study it only in male hamsters, because females’ hormone cycles would make the data too messy. Meanwhile, women are left to struggle through debilitating ailments with inadequate treatments while medical research still heavily favors male bodies.

Robinton is determined to bring her particular blend of human warmth and cold research chops to the principle that it’s possible to give a damn about women’s well-being—and use science to do so. Her first target, which she’s tackling through a new venture called Oviva Therapeutics, is menopause.

Menopause (the end of a woman’s menstrual cycle) is a huge physiological and life event that our medical system typically treats as something of a hiccup. Its symptoms afflict a vast majority of women, disturbing to varying degrees their sleep, mental health, cognition, and sexual function—sometimes for years on end. It also marks the inflection point from relative youth and fitness to the gerontological decline of older age. After a woman’s last cycle, the risks of heart disease, bone fragility, Alzheimer’s, and other disorders all leap, but it’s not entirely clear what role menopause plays in those risks.

(Author’s note: While this article uses the term “women” broadly in discussing ovarian health and menopause, we recognize and appreciate that people of other genders, such as nonbinary people and transgender men, may also experience menopause.)

When Robinton dug into the research about menopause a few years ago, she recalls feeling shocked. “I was like: Oh my god, so many women hit 50 and sex is painful or they don’t want it, they don’t feel well, they can’t sleep, and we just accept this as a given for half of their life?”

“I want to sleep well, I want to have a great sex life, I want to feel great and be energetic.”

The importance of living to our healthiest potential is personal to Robinton, a lifelong athlete who has made a second career modeling for top fitness brands like Adidas, Lululemon, and Athleta. Her life partner, Adam Cobb, is a fitness and performance coach. She values good sleep so much that as a kid she sometimes put herself to bed at 8pm. As Robinton sees it, menopause is lurking out there in every young woman’s future, waiting to steal our potential. But she’s not content to let it stay that way.

“Everyone is always talking about how hot longevity is, but [ovarian aging] is such an obvious early signal and early intervention point that could impact half the population if someone cared enough to put the money into it,” she says.

Her startup, Oviva Therapeutics, backed by Cambrian Biopharma, aims to create therapies to interrupt menopause and prolong women’s ovulating years deep into their lives, not only extending their fertility but potentially extending their youthful health as well. In approaching that work, Robinton and her colleagues are asking medical questions so big that they border on the existential: Can we not just slow menopause, but stop it altogether? And what happens if we do?

Pushing back the fertility cliff

For all the microscopic detail in her doctoral and postdoctoral research on the molecular underpinnings of cells’ development, Robinton’s life’s work is essentially well-being. It started in her childhood bedroom in Palo Alto, California, at around 2 o’clock in the morning. Her older sister, Lily, had recently been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Each night, their father came into Lily’s room in the wee hours to check her blood sugar as Lily screamed in protest against the pricking of her finger. Then, on a couple of nights, Lily’s sugar crashed—a life-threatening event. Her father found her unconscious, and Daisy, age 7, watched through the glass door that separated the sisters’ bedrooms as her father straddled Lily and furiously rubbed glucose gel into her gums until she came to, confused and crying.

Lily, the oldest of the five Robinton siblings, had been their ringleader. But Daisy recalls that after the diabetes diagnosis, “she really went into a shell.” So Daisy decided on those frightening nights that she would do something to help, and she ultimately settled on science “as a way to unlock potential for people.”

Her epiphany about the chasm in women’s health research and investment came later, around age 30, when she ended a long-term relationship and started to worry about her biological clock. She consulted with a fertility doctor and was staggered by everything she hadn’t known—and most women don’t know—about her own biology. For instance: Every month we ovulate one egg but also lose approximately a thousand more, summoned from our limited supply but not fully developed. If a woman misses her natural fertility window, the in vitro fertilization process is brutal on her body, and its likely success rates are low. And finally, somewhere in our 50s, our ovaries shift into their old age, even as the rest of our bodies remain younger, and for many of us, our health and quality of life begin to deteriorate from there.

“That actually scared me a lot more than the fertility cliff,” Robinton recalls. “These things are important to me. I want to sleep well, I want to have a great sex life, I want to feel great and be energetic.” Yet our only real treatment for menopause—hormone replacement therapy—dates back 50 years and brings a modestly increased risk of breast cancer and other health problems along with the relief it provides from hot flashes, night sweats, insomnia, vaginal discomfort, bone loss, and brain fog. “Historically in the practice of medicine for women there’s this accepting that some degree of suffering is just normal and there’s no effort to alleviate it,” Robinton says. “It felt like such an egregious example of neglect that I could contribute to.”

Robinton, who now lives in Los Angeles, was deep in reading on women’s health when she met Cambrian Biopharma Founder and CEO James Peyer for coffee and told him her thinking. Cambrian’s focus is lengthening the human healthspan, the period of life spent in good health. Their specific approach is to develop medicines to prevent the diseases of aging before they happen. Peyer asked Robinton to join Cambrian to find a way to translate her research into a medicine to slow the ovaries’ aging—in other words, to preserve the ovaries’ store of viable eggs and hopefully, in so doing, keep a woman’s monthly cycle turning. “We don’t have any good treatments for menopause once it’s happened, and we are doing nothing to prevent it, and all of those things combined make it a fantastic opportunity,” Peyer says. “Also, half the population is going to get it and most of them don’t want to. The market size has never really been estimated because no one has ever taken a real shot on goal.”

Robinton and Peyer’s gamble was this: We still don’t know exactly what causes menopause, but it seems likely that the hormone changes that come with the depletion of eggs over time are the trigger. Nor do we understand why that shift ushers in the risks of aging across the whole body. But it stands to reason that delaying the first could delay the second. In other words: recognizing the problems that occur in the presence of menopause, it was time to ask what would happen in the absence of it. If, that is, Robinton could find the right biochemical key to unlock the ovaries’ natural timeline.

Modeling and the science life

Asking big questions has always come naturally to Robinton, who notes that she’s the daughter of an artist and an engineer. One of her early mentors, UCLA Professor Bob Goldberg, remembers that she stood out as a college freshman for her broad, conceptual thinking and unabashed willingness to ask off-the-wall questions. Her longtime friend Kyla Searle sees her as a natural storyteller who is now using science to try to rewrite the story of women’s lives. “I think Daisy uses the scientific model to really openly and curiously consider the world around her,” Searle says.

That balance between the expansiveness of ideas and the nitty-gritty of tiny details has played out in the dialogue between Robinton’s twin careers of science and modeling—which sometimes created tension, but which Robinton believes has benefited both pursuits.

She started modeling her senior year in high school to stay busy when a torn ACL stopped her from captaining the soccer team and working as a restaurant hostess. She landed her first big job with Abercrombie & Fitch soon after and kept modeling part time in college. Even as she toiled in the lab and worked as a teaching assistant for the molecular biology classes taught by Goldberg, she dated actors and attended afternoon pool parties with LA’s glitterati. Yet she kept quiet about the other half of her life among scientists.

“I wanted to be seen and received by my colleagues and peers, and I thought that would make it more difficult for me to be respected and taken seriously,” she says. And not without reason. Once, when she was presenting a poster at an international stem cell conference, wearing a sleeveless knee-length Calvin Klein dress from the business casual section of Macy’s, a senior male faculty member, trying to be helpful, advised her to wear something else because she was distracting people from her ideas. Robinton remembers thinking, “If that’s something that’s going to cost me a job or opportunity, I don’t want that job anyway.”

But modeling jobs paid her way through UCLA, with her parents’ budget already stretched by five kids, and later supplemented her meager PhD stipend at Harvard. More than that, modeling became a part of her scientific practice, as it allowed her to release her natural playfulness and connect with the world outside the lab. Sitting in the styling chair for hours before a shoot, she would explain her scientific work to makeup artists and fellow models, then bring their real-world questions and concerns back to her research. “The modeling provided this kind of spaciousness for getting out of the weeds,” Robinton explains. “And I think that’s really important when you’re doing super detailed, rigorous work, because you can get so focused in on your little question that you’re working on. It’s really important to remember the big picture.”

Preserve eggs and prevent menopause

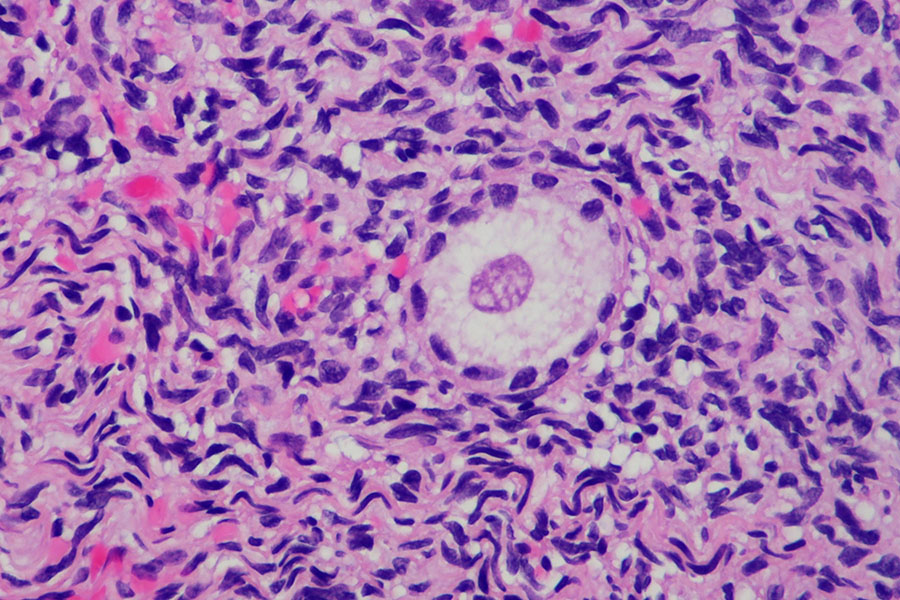

Robinton’s inquiry into women’s health ultimately led her to a small, but potentially powerful, detail: the ovarian hormone AMH. Anti-Müllerian hormone is released in the ovary around newly maturing eggs. It prevents additional eggs from maturing, effectively holding them in reserve. A woman’s natural AMH levels typically peak around age 25, then gradually decline to undetectable levels after menopause.

When Robinton went searching the existing science for potential keys to postponing menopause, tweaking AMH was one of the only viable possibilities she found. Two Massachusetts General Hospital researchers, Patricia Donahoe and David Pépin, were working to map its chemical structure (which they and colleagues ultimately did in 2021). And Pépin had developed a lab-grown, “recombinant” form of AMH that he was testing as a way to maintain the ovary’s reserve of eggs. “This was really brand new stuff,” Peyer says, “although it feels a little like work that should have been done 15 years ago after the genome was sequenced.”

Oviva could be running clinical trials for menopause prevention by the end of the decade.

Donahoe, Pépin, and Robinton agreed to team up. Just a week before they made their successful pitch to Cambrian to fund Oviva in early 2021, Robinton learned she was pregnant, and soon after that learned she was carrying a girl—a girl who would grow her entire life’s supply of eggs in the womb but naturally start losing them before she was born—and another future woman who deserves better.

Oviva is now testing Pépin’s version of recombinant AMH as a potential drug. Still in preclinical development, it has been studied extensively in mice, and further work is being done in several other species, such as cats. The company plans first to seek approval for it as an ovarian function treatment, for a specific medical indication to be announced in early 2022. But that’s just a stepping stone to the bigger goal of testing it to stave off menopause, perhaps for as long as a woman wants, perhaps forever. For now, recombinant AMH is too expensive to manufacture to be able to give women a daily dose for years. But Peyer says they have some ideas for how to make that “cheaper and cheaper—to target pennies a day,” Peyer says, “and when we get to that point we can think about slowing menopause.” If their version of recombinant AMH proves safe and effective, he predicts Oviva could be running clinical trials for menopause prevention by the end of the decade.

That, at least, is the plan for now, though plenty of things could get in the way. “The number one thing on my mind is that our hypothesis about menopause is that it’s based on the depletion of the ovarian reserve, but no one’s ever tested that, because there has never been a tool to stop the ovarian reserve from depleting,” Peyer explains. Similarly, no one has ever had the opportunity to find out what else happens in the body if you preserve eggs and prevent menopause. Robinton believes, based on her research, that it will propel women through more years of living healthily, living to their best potential. “But the real answer,” she says, “is we don’t know.”

An incredible, little thing

Regardless of what Oviva discovers through its work with recombinant AMH, Robinton is in pursuit of something bigger. Even if AMH doesn’t work as hypothesized, she and Oviva hope to build a trend of more and more reputable scientists investigating real treatments for women—and in so doing, bring the field more of the attention and investment it deserves. All the while, they’ll continue researching new leads. Through the AMH work, “we’re getting this gold,” Robinton says, “this incredible data trove of how our cycles work and how our bodies respond when you change one little thing.”

One little thing, of course, can be the difference between good and bad health at the smallest and largest scales. Most of Robinton’s prior work, from stem cell genetics to the developmental roots of neurodegenerative diseases, has centered on the tiny biochemical cues that change a cell’s destiny. She wants to know: What signals must be present for a cell to reach its ultimate potential? What happens when a signal goes awry? And what does that mean for the potential of the whole organism?

“I weirdly link the two things, personal identity and cellular identity,” she says. “They really feel connected in my brain and my personal life and my interest in studying science.”

After all, each of us starts as a single cell that divides into two, then four, then eight. Each of those cells holds the potential to grow any cell in the body, and tiny signals can send it in totally different directions—which is how Robinton also sees people, as the rightful owners of limitless potential.