China Doubles Down on the Double Helix

From sleepless startups to huge sequencing centers, genomics is booming in China. Will other countries get left behind?

On the lush new campus of Fudan University in Shanghai this past Sunday, the auditorium in the life sciences building filled beyond capacity with about 300 students and biotech executives. The celebrity they came to see was George Church.

The renowned Harvard geneticist had come to Shanghai to launch the Chinese chapter of the Personal Genome Project or PGP, a nonprofit organization he founded in 2005 to recruit volunteers who share their DNA readouts with researchers. The goal is to spread insights about how genomes relate to traits and diseases, and in turn, speed the pace of progress in applying genomic data to medicine. Since 2012, the network of researchers involved in the data-sharing effort has expanded to Canada, the United Kingdom, and Austria. But now China could give the project its biggest boost yet. Genomics is booming in China, and the country could dominate an increasingly valuable industry.

The Chinese government plans to pour 60 billion yuan ($9 billion) into a national precision medicine initiative before 2030. That’s a lot of money: a similar effort in the United States was launched in 2015 with $215 million in funding. As part of research into precision medicine techniques, millions of people’s genomes will be sequenced in China in the next few years, says Michael Chou, co-founder of PGP China and a lecturer in Harvard’s genetics department. In 2016, the state-owned Yang Zi Investment Group built a sequencing center in Nanjing that’s capable of sequencing the genomes of 400,000 to 500,000 people a year. That would be roughly equal to the total number of people who had ever been sequenced as of last January, according to Illumina, the leading maker of sequencing machines.

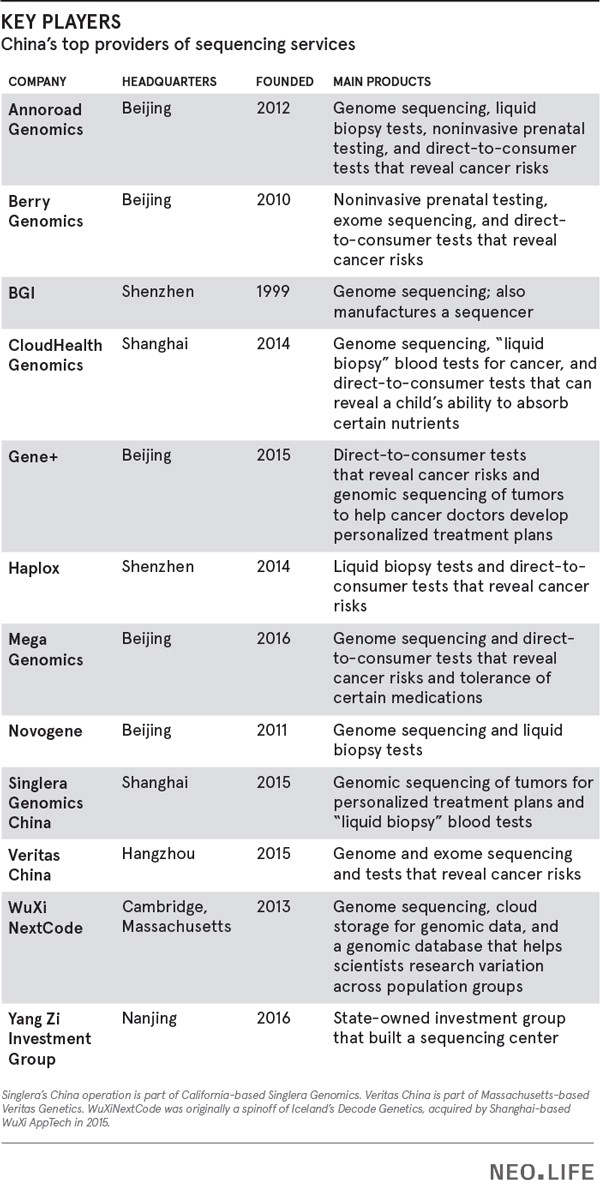

About 30 percent of the world’s sequencing machines were in China as of 2015, but the country has been gearing up to increase its share. A wave of investment in genomics has crested over the last six years as other industries, especially real estate, began to falter. The genomics business has gone from being overshadowed by one company, the Shenzhen-based BGI, to now having at least 10 companies equipped with the latest sequencers from Illumina, which can decode genomes for about $1,000 apiece. Nobody can offer a precise count of players in the market because so many companies are trying to amass funds and purchase sequencing machines. In addition to these homegrown sequencing startups, Chinese companies with global ambitions such as WuXi AppTec have been buying up stakes in international genomics companies.

The more genomes that get sequenced anywhere in the world, the better for researchers like George Church. When companies or organizations participate in the Personal Genome Project, they ask people who are being sequenced whether they want to share their name and their data and take part in follow-up research. Then scientists who spot something of interest in a genome shared by a volunteer — a particular genetic variant, let’s say — will be able to follow him or her over a span of years. Church says 10,000 people have signed up so far.

An FBI agent who follows genomics technologies warns that “the U.S. may cede the lead in innovation” to China.

With volunteers and data from the world’s most populous country, the Personal Genome Project could develop better ways of interpreting the role of genes and the environment in various diseases and traits. “The whole point is to produce something like Wikipedia, where software developers around the world can contribute,” says Church, who believes China can provide both diverse sets of genomic data and a large computer science workforce needed to create useful software applications that rely on genomic data. “Developed locally but deployed globally,” he says.

Beyond the potential benefits for research, it’s less clear what it will mean for the worldwide genomics industry to have so much sequencing going on in one country. By accumulating ever-larger pools of genomic data, from inside the country and outside it, China is also laying the groundwork for whole new industries that tap the value of this data. In fact, Edward You, a supervisory special agent at the FBI’s Biological Countermeasures Unit, has been warning that if China has the largest storehouses of valuable genomic data, the competitiveness of U.S. biotech companies and even American national security could suffer. “There is a theoretical risk that the U.S. may cede the lead in innovation in the burgeoning and dynamic biological-cyber realm,” You told the Senate in March.

Luring customers

One of the organizations in PGP China is a company called CloudHealth Genomics. Its chief technology officer is a former Harvard genetics researcher, Winston Patrick Kuo. These days, Kuo says, he sleeps two or three hours a night. During the day, he attends meetings and checks in on staff members at the company’s headquarters on the outskirts of Shanghai. When night falls in China and the day begins in the U.S. and Europe, he collaborates with researchers there. “I do everything globally,” Kuo tells me.

We’re in a small meeting room on the fourth floor of the company’s headquarters, which is still mostly empty because it’s reserved for future startups that might need office space and access to sequencing machines. In particular, CloudHealth wants to host startups that design direct-to-consumer applications of genomic data, even if it doesn’t directly invest in such companies. The idea is to expand the ecosystem, so to speak, giving even healthy people an incentive to get sequenced. “It’s so exciting,” Kuo says.

Since being founded in 2014, the company has sequenced all sorts of samples — plant, animal, and human — sent by academic and government research institutions. In June, CloudHealth announced a precision medicine initiative with a Mongolian NGO to combat nutrition-related diseases. The idea behind this kind of research is to track the genetic origins of any patient’s medical condition and better predict how the patient will respond to particular drugs.

If efforts like these are successful, they will improve China’s data infrastructure for precision medicine, an initiative that is similar to ones in other countries, including the United States, which aims to collect genomic and other health data from a million people. By 2050, when China is expected to have more than 329 million people older than 65, more precise ways of dealing with age-related diseases such as cancer will be urgent. The country has employed DNA sequencing in some clinical settings — local health authorities have a network of providers that can sequence the DNA a fetus sheds into the mother’s blood to spot Down syndrome — but it still lacks comprehensive databases about a wide range of conditions, including rare genetic disorders and cognitive development problems. Such databases would be critical if doctors are to develop more personalized treatment plans for patients. And building such databases is slow work. Haplox, a Shenzhen-based genomics company, is working on a project to sequence the DNA of 10,000 cancer patients and high-risk individuals.

At CloudHealth, supporting the government’s initiatives might not be enough to support the business. But finding mainstream consumers to get sequenced is tricky, at least for now. The company charges 29,800 yuan ($4,504) for a whole genome sequence and analysis, while the average monthly salary in Beijing is 6,906 yuan ($1,043). The company’s chairwoman, Beryl Gao, is trying to line up former clients of her real estate business to get sequenced.

One sequencing company is offering discounts during an online shopping festival and opportunities to win an iPhone X.

CloudHealth also is trying to reach mainstream consumers in other ways, playing off their desire to stay healthy. It’s working with clothing companies to develop products that consumers can use to monitor the chemical makeup of their sweat, body temperature, and other vital signs. Tiny sensors embedded in T-shirts can gather the wearer’s health data and send it to a centralized database through an app. Even though it’s not genomic data, it’s still a component of an individual’s health. And for a company like CloudHealth, the more data it has, the better its products will become. “Right now,” Kuo says, “we have to at least start to plan the framework.”

Meanwhile, one of CloudHealth’s rivals, Haplox, hopes to capitalize on one of China’s biggest consumer events: an online shopping festival that occurs on November 11 every year. It was started by Alibaba Group in 2009 and brings in billions in sales. This year, people who get their DNA sequenced by Haplox will enjoy special discounts and opportunities to win an iPhone X.

Asymmetry

The FBI press office said Agent You would not comment for this story. But it’s clear that he worries not only about the global business ambitions of Chinese companies but even international research partnerships among scientists. “Theoretically, the combination of genetic data through research collaborations, legitimate business agreements, and hacked information being exfiltrated to China would be the largest, most diverse dataset ever compiled,” he said in his Senate testimony last winter. “The lack of understanding the breadth and scope of the bioeconomy and the reliance upon the generation and aggregation of data has led to the potential asymmetry in access and capabilities, which could impact overall security.”

Asked by proto.life about such concerns, George Church dismisses them as a “paranoid” view. “We need to be less chauvinistic about such matters,” he says. “Sharing is the thing that is the barrier, I think, to progress in medicine. We need to have a lot more international sharing, and I’m quite looking forward to it.”