Major corporations are applying the lessons of cognitive neuroscience to get the American public buying.

Why do people purchase Tide brand laundry detergent rather than Purex or Persil? What drives consumers’ allegiance to a brand, and what compels them to abandon it? In the end, the choice of the best detergent for one’s washing machine should be based on tangible factors, including price and effectiveness. So why isn’t that the case? A 2021 PWC study shows that between 80–86 percent of American consumers are willing to pay more for speed and convenience regardless of the quality of the product, and an equally impressive 18 percent are willing to pay more for luxury and gratification services. This sort of consumer behavior has implications that go well beyond what gets rung up at the register.

Well, that’s the territory of neuromarketing, the field of study that aims to understand how the human brain is functionally affected by advertising and marketing approaches.

The science of neuromarketing is an offshoot of the field of cognitive neuroscience. However, according to Christophe Morin, an adjunct professor at the Fielding Graduate University who has pioneered this approach to understanding consumer’s choices, neuromarketing “goes beyond what people can articulate.” He believes that putting the brain at the center of consumer behavior allows researchers to consider data that are not simply self-reported by the consumer, but also garnered biometrically through the use of technologies like EEGs, fMRIs, and biochemical sensors.

Why?

According to Harvard neuroscientist Gerald Zaltman, 95 percent of purchases are emotionally driven. Thus, customers’ appreciation of a product is not based on the brain weighing the reasonableness of a purchase based on classic economics. Rather, it takes place at the saurian (reptilian) level of the brain where the fight or flight reaction arises and in the areas of the limbic system that preside over emotions, like the amygdala—where anxiety dwells—and the anterior cingulate cortex of the brain, where uncertainty and contrasting sentiments reside. As confirmation of the areas of the brain where these reactions occur, experiments to decode emotions in the brain show that when these regions are damaged, people cannot make a choice and end up acting on impulse and whim.

But it doesn’t take brain damage to act on impulse or make a consumer choice that’s not in your interest. Neuroscience can quickly interrogate, even manipulate these reactions with the help of data analysis and AI—for understanding how the mind works, for marketing purposes, and even for advancing socio-political goals.

Pepsi, Coke, or Trump?

In 2004, Baylor College of Medicine researchers were the first to show how marketing could have broad effects on consumers’ brains and influence their choices. They did an experiment to understand why people preferentially purchased Coca-Cola over Pepsi, even though the two drinks taste pretty similar (a fact driven home to American consumers in endless “Pepsi Challenge” ads since the mid-1970s). Reprising the early days of the famous marketing campaign, researchers served participants two unmarked cups containing Coca-Cola in one and Pepsi in the other.

Asked which they prefer, people chose Pepsi overwhelmingly when they didn’t know which was which. However, when given the same drinks with one of the cups labeled “Coke,” they chose the Coke over the Pepsi. Furthermore, when researchers did the opposite and labeled one beverage “Pepsi,” people chose the presumptive Coke cup even more often, confirming that consumers were influenced by brand recognition and Coke’s allure was greater than Pepsi’s.

Baylor’s fMRI study correlated those choices with brain activity. During the anonymous test, activity was the highest within the ventromedial part of the prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain involved in emotional and self-referential processing. In contrast, when people knew the brand, the hippocampus and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex were recruited, revealing that the subjects were retrieving their prior experiences with the brand during the test. Furthermore, a study involving people with a compromised ventromedial prefrontal cortex suggests that a lesion in this area, compared to subjects with lesions in other brain areas and to healthy subjects, overpowers brand influence on preferences.

“We could in principle one day measure what people think and not just what they say or what they do.”

Similar results were obtained in another study about the role of ambiguity in activating the area of the brain that reacts to brand awareness. In the study, people’s brains were scanned as they chose between practically identical vacation packages. Other than a few minor semantic differences in the way the packages were presented in the pamphlets, the choice really came down to a question of two competing brands: Thomas Cook versus TUI. In this case, brand recognition also made a difference, activating both the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate.

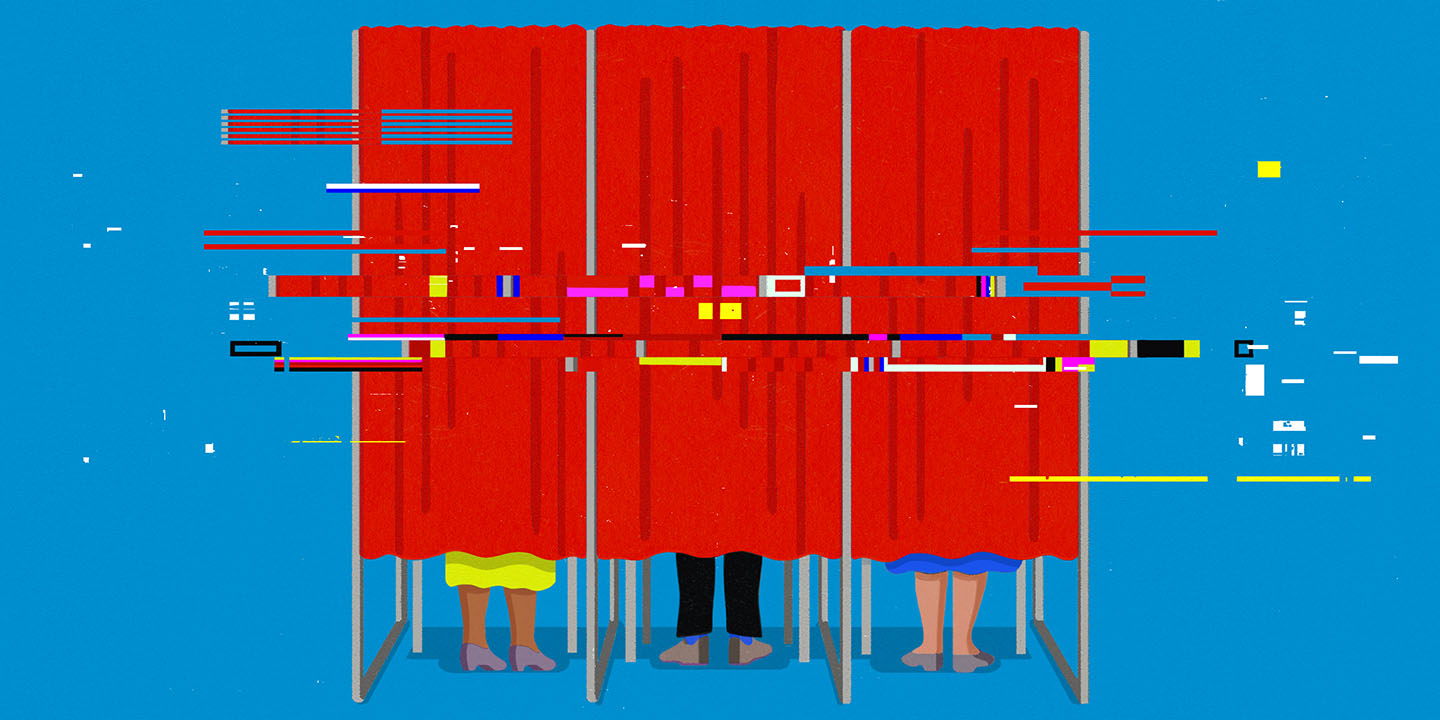

Much has been written about the Trump campaign’s neuromarketing 2.0 tactics relying heavily on digital technology during the presidential election of 2016, in which the convergence of big data, artificial intelligence, and social networks eliminated the need to test people in a laboratory setting and allowed them to micro-target voters with extraordinary precision. This is based on a concept in cognitive psychology known as “congruity theory,” which suggests that voters will select politicians whose perceived traits match their own.

First, massive amounts of data on individual consumers were collected using digital learning channels such as digital eavesdropping, face recognition, and image identification. Next, researchers used machine-learning algorithms to observe, test, and analyze political emotions and behavior to understand their political relevance. Then a psychometric profile of the individual consumer was developed and successively fed back, through social media, into the candidate’s online personality, his message, and all the other political instances of interaction between the campaign and voters. The study reports that some neuromarketers dubbed this tactic the “buy button” because it defines the political issues that can be pushed like buttons to encourage the voter to vote in the desired way.

A galaxy of companies and startups

While the debate about the legitimacy and consequences of such data collection in American politics rages, the field of neuromarketing marches on. Recent advances in brain-imaging technologies and data collection combined with applying a cognitive language processing framework known as sentiment analysis have transformed neuromarketing from a curious assemblage of peculiar studies into an energetic new field studied by well-respected neuroscientists.

According to Dan Ariely, a psychology professor at Duke University and founding member of the Center for Advanced Hindsight, neuromarketing research is emerging as a potentially powerful window into the neuronal basis of human motivation. “The thing that is most exciting about neuromarketing is the idea that we could in principle one day measure what people think and not just what they say or what they do, and maybe we can see the steps leading to a decision—its buildup over time,” he says. “It is too early to say that these things are for real, but that is the promise.”

It may be too early to say if existing neuromarketing practices are accurate or effective, but that has not impeded a burgeoning galaxy of small and medium-sized companies and startups, often founded within academic accelerators, to rush into this new space. Neuromarketing companies like NeuroFocus, Spark Neuro, Imotions, and Immersion Neuro are leveraging techniques developed to study attention deficit disorder and Alzheimer’s disease. They’re also employing a new class of cerebral scanners as well as smartphones, smartwatches, smart glasses, and performance trackers to ply mega-corporations such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi, large military contractors, auto manufacturers, the telecommunications industry, major universities, and famous food brands with promises of increased sales based on findings in the field.

In the brain, the journey from memorable and enjoyable to predictable is awfully short.

“We are democratizing neuromarketing,” says Paul Zak, the founder and CEO of Immersion Neuro. Zak is also a professor of economic sciences, psychology, and management at Claremont Graduate College in California, illustrating the interlacing between industry and academia. “Five years ago, we launched a platform where anybody can do this using datapoint[s] from smartwatches and apply algorithms in the cloud to infer brain activity,” Zak says. “We are finding that this state of neurological immersion where you are attentive but also emotionally engaged by an experience or a message not only motivate[s] people to take action after they have that experience—be it purchasing, sharing on social media, or with your congressperson—but also they consider it highly memorable and enjoyable, and [they are] compelled to do it again.”

In the brain, the journey from memorable and enjoyable to predictable is awfully short. So short, in fact, that more than a few scientists, researchers, and policymakers have started to express concerns about the discoveries made by neuromarketers to compel consensus across social media and in social policy formulation. And these concerns are not unwarranted for a line of research that Morin began in 2002 with a DARPA investment to understand what people would do after receiving a message of an emotional nature.

Extreme neuromarketing manipulations like the Cambridge Analytica and Facebook cases are rare. However, the business of neuromarketing is booming, with one estimate putting the global neuromarketing market at $770 billion by 2025. New technology is getting cheaper and more accurate and is used for everything from monitoring employee performance to gauging moviegoers’ reactions at cinemas to evaluating the efficacy of psychiatric applications. As a result, abuse seems inevitable, according to some experts.

The idea that neuromarketing could be used to manipulate people didn’t escape Morin. “Neuromarketing at the beginning of its history was a set of methods that would be employed ethically and safely. I wrote the code of conduct,” reiterated Morin. “The intent of neuromarketing wasn’t to drive the creation of advertising that is subliminal but to record information while people are exposed to advertising stimuli.” Nevertheless, Morin welcomes the new possibilities that the diffusion of the tools of neuromarketing is allowing.

“For the first time, we have the possibility to identify these abuses and how they work on the elderly, the disabled, the youths, and maybe for the first time we can do something about it,” concludes Morin.

Editor’s note: At the time of publication, Dan Ariely’s unrelated 2012 paper had recently been retracted over concerns about the integrity of the data used.