Some studies show it’s better than SSRIs—but there’s no incentive to invest in clinical trials.

Sudhir Gadh, a New York City-based psychiatrist and commander in the United States Navy Reserve, believes that the medical establishment has overlooked an effective and cheap medication to fight the epidemic of depression. That overlooked drug is lithium—in low doses. Gadh is a solo practitioner and not affiliated with any university or research institution, because he claims that no one is interested in funding his research.

It’s odd that this indication has been overlooked because as far back as 1949, Australian psychiatrist John Cade first showed lithium had a therapeutic effect for mania. Prescription lithium is commonly used today to treat the mania that is part of bipolar disorder, an illness that can cause intense shifts in mood, energy levels, and behavior. Although manic and hypomanic episodes are the most prominent symptoms of bipolar disorder, most people with the illness have symptoms of depression as well. Lithium received regulatory approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1970 for treatment of acute mania, and in 1974 as the first approved treatment for prevention of recurrences in bipolar disorder (manic-depressive disorder was officially changed to bipolar disorder in 1980).

Knowing lithium’s success in bipolar disorder, Gadh thought it might be useful at lower doses for unipolar (major) depression. In fact, he found that among his patients, lithium was not only an effective alternative to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) but also a better treatment, because SSRIs work in only half of patients as a standalone drug. And at low doses, the side effects are minimal to none. “Additionally, lithium levels in the blood can be measured and serve as a guide to adjust the dose if needed,” Gadh says.

There are studies that both support and question Gadh’s view. A 2017 study of 123,712 people hospitalized for severe unipolar depression in Finland from 1987–2012 found that lithium was not only more effective than SSRIs at preventing return trips to the hospital, it also outperformed two other common treatments: a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) and an atypical antipsychotic. (Atypical antipsychotics work on both the dopamine and serotonin receptors in the brain. The first generation, or typical, antipsychotics, only work on dopamine receptors.)

Without patent protection, there is no money to be made from investing further in the drug, which is in fact a trace mineral available all over the world.

However, a 2006 review by the Cochrane Library of eight randomized controlled trials involving 475 patients did not substantiate that finding, although the authors cautioned that “the number of participants in the studies was small, and the included studies had methodological shortcomings.”

But there’s more to this story than meets the eye. Because lithium has been around so long, nobody owns a patent to it, and without patent protection, there is no money to be made from investing further in the drug, which is in fact a trace mineral available all over the world.

Gadh notes that the Greek founder of modern medicine, Galen, recommended a local lithiated spring to all his patients. “As recently as 100 years ago, visiting such springs in the U.S. was common. So much so that the first bottled waters were sold as lithiated water,” Gadh says.

In addition to drinking water, nutritional lithium comes from grains, vegetables, mustard, kelp, dairy, fish, and meat and is considered safe in small amounts. Although not regulated in drinking water, the United States Geographical Survey (USGS) reported last year that about 45 percent of public supply wells and about 37 percent of U.S. domestic supply wells have concentrations of lithium that could present a potential human health risk. The most elevated lithium concentrations were measured in four aquifer systems in the western United States where 10 million people rely on groundwater for drinking water.

Gadh says he is criticized constantly for not doing a randomized clinical trial (the gold standard for establishing a drug’s efficacy), but all his requests for funding have been turned down. “No one is going to fund a trial for lithium for major depression. As it is no longer under patent protection, there is no financial incentive to do so.”

Gadh is a believer

Gadh believes there is increasing evidence of lithium’s benefits to anyone with nearly any psychiatric condition, and even those without one. On his website, he writes, “examples include the improvement of anxiety, reduction of self-destructive behavior for people with a history of abuse, prevention and reduction of suicidal thinking and behavior, deepening of sleep and the reduced occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease.” His work is in line with the work of other researchers as reported by proto.life in an article exploring the idea of microdosing lithium, possibly even for everyone.

“There is no downside to trying lithium at low levels. And the potential upside can be life changing.”

Gadh’s claims are similar to those made by lithium’s consumer manufacturers—that it improves brain health, longevity, and promotes well-being, which they can get away with because the FDA does not have the authority to regulate supplements. That’s one reason Gadh says consumers should proceed with caution before using them.

The protocol Gadh recommends to his patients is nutritional or “low-dose lithium,” which is dramatically lower than the doses used to treat bipolar disorder. It’s also in a different form, called lithium orotate, as opposed to the lithium carbonate found in prescriptions.

Gadh says that low-dose lithium and especially nutritional-level lithium are safely cleared by the kidneys daily. “The amount that would be harmful to the kidneys would be over 200 times [above nutritional levels] for several years. Anyone with kidney dysfunction should consult with a specialist. However, there are recent studies showing kidney function improvement with lithium supplementation.”

proto.life asked Robert Klitzman, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, about the use of lithium for unipolar depression. He says, “lithium is very effective in treating bipolar disorder and as an additional treatment for patients on antidepressants, or those whose depression has not responded to SSRIs or other antidepressants.”

However, he warns, lithium has several side effects, including kidney problems and weight gain. Which means that people taking the drug need to have their lithium blood levels and other markers of body chemistry regularly checked and monitored, “which can pose challenges,” Klitzman says. That’s not the case with SSRIs.

Lithium as a repurposed drug

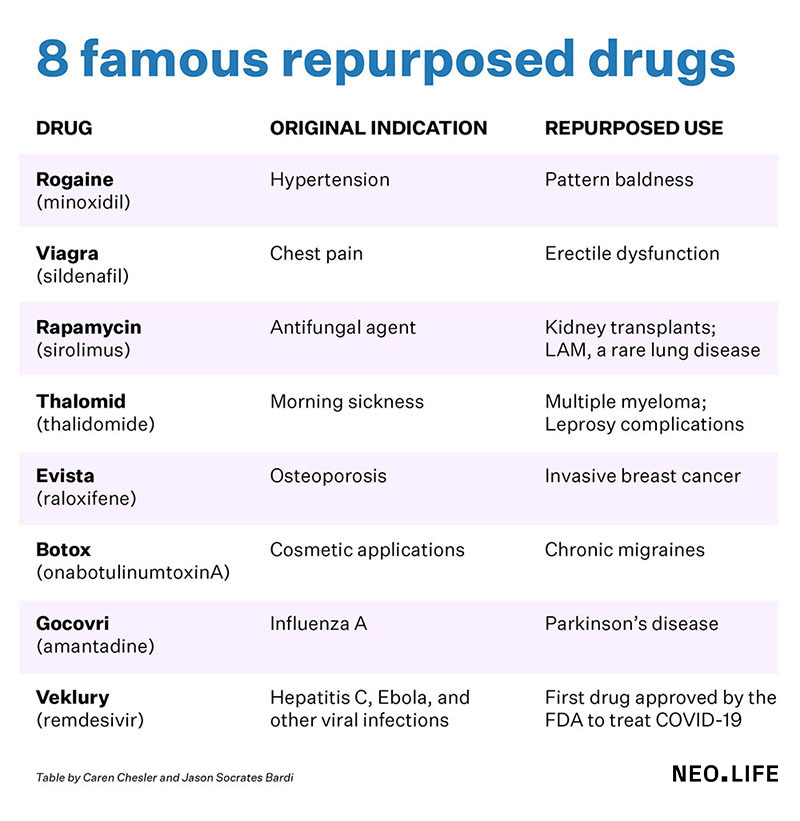

Gadh’s work with low-dose lithium is in line with the trend to use older drugs to treat illnesses for which they were not originally approved. During the pandemic, the hunt for existing drugs to treat COVID-19 had mixed results (think hydroxychloroquine) and one great success, remdesivir. Remdesivir was a pre-existing drug candidate developed by Gilead Sciences for the Ebola virus. It was FDA approved in October 2020 for the treatment of COVID-19 through emergency use authorization programs for adults and children 12 and older under the brand name Veklury. (Earlier this year the FDA expanded that approval to young children a month or older.)

Thalidomide is often considered the poster child of repurposed drugs. Although never approved in the United States, as many as 20,000 Americans were given thalidomide in the 1950s and 1960s as part of two clinical trials. And in Germany, England, and other countries where it was approved, it’s estimated that thousands of babies were born with severe defects tied to their mothers’ use of thalidomide. But in 2006, thalidomide was resurrected when it became the first effective new drug to treat multiple myeloma in decades. A decade before that, it had been approved to treat complications due to leprosy.

Gadh is proposing using lithium as a repurposed drug for unipolar depression. He says in treating depression or anxiety, 20mg of elemental lithium is beneficial, while severe mental illness requires nearly 200mg. “It is this kind of outside-the-box acting that may lead to new uses for natural or synthetic medications. Antidepressants, after all, were discovered by accident, from the treatment of tuberculosis patients in New York.”

He advises that people should speak to their doctors about trying a course of low-dose lithium if they do not have an effective response to the medication(s) they are taking for depression. “There is no downside to trying lithium at low levels. And the potential upside can be life changing.”