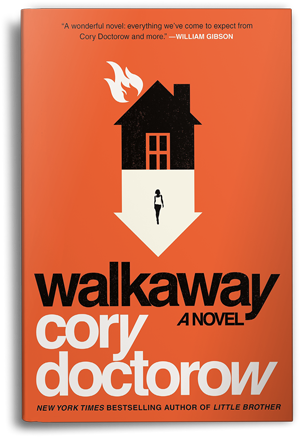

BOOK REVIEW

Makers of the World, Unite

Cory Doctorow’s novel “Walkaway” envisions a future in which the jobless masses co-opt automation technologies to ensure their freedom.

What happens when technology becomes so efficient that the vast majority of people become unnecessary as workers? Would the 99% become people of leisure? Would competition for jobs intensify, widening the gulf of inequality?

Cory Doctorow’s novel Walkaway imagines a future where the wealthy have created an economy of artificial scarcity, leaving billions scrambling for jobs and going into extreme debt just to get their kids through high school. At the same time, though, people in this imagined future have another option, thanks to the fact that they can use highly versatile and efficient manufacturing technology to form self-sustaining cooperative communes. To join one, a person simply has to decide to leave the capitalist “default” world — that is, to walk away.

The novel follows three disillusioned 20-somethings — an heiress, a snarkster, and a guy whose parents saddled him with all of the top 20 names for boys from the 1890 census (Hubert, Cecil, Ollie, etc.) — as they walk away from the late 21st century’s default society, fall in love with veteran walkaways, and become embroiled in the walkaways’ struggle against “zotta-rich” robber barons. The “zottas” harass and vilify the walkaways, while simultaneously restricting their access to education and resources under the guise of meritocracy.

Doctorow — who is the co-editor of BoingBoing, a longtime Internet personality, and the sort of person who can get Ed Snowden to write blurbs for his book jackets — puts forward loads of interesting ideas about the future of technology and media and explores the ways that human psychology sometimes keeps us from living up to our ideals.

Though it’s set in a world where wealthy elites aggressively enforce their own supremacy, Walkaway is very much a utopian novel, more in line with Aldous Huxley’s Island than Brave New World. Walkaway plays with the idea that technologies that would be horrifying in the hands of a militaristic state or an insatiable oligarchy could be transformative and liberating if shared freely and equitably. For example, extensive data networks can be used to altruistically share information and ideas or to surveil and sic deadly drones on enemies. At times, the vein of hope running through Walkaway verges on unearned optimism (in a world nominally wracked by “Old Man Climate Change” no one ever seems to have a problem accessing water), but given the current glut of dystopian and post-apocalyptic novels that depict human nature as ruthlessly self-centered and violent, the optimism is refreshing. The main characters are mostly people of color and LGBTQ, and eventually they band together as a very non-traditional family unit.

But it’s clear that the characters are meant to take a back seat to the real star: walkaway culture itself. The walkaways are makers, collaborating to build communal homes from scavenged parts, presumably through advanced 3-D printing (we don’t get many descriptions of the printers, how they work, or what their limitations are). The self-governance of the walkaway camps is very Reddit-on-a-good-day, where everyone makes design suggestions and reaches a consensus through discussion. The book is steeped in the sort of slang and debates you’d hear around the MIT Media Lab.

The most memorable aspect of the story is a tech development race. Both the “zotta-rich” tycoons of default and the researchers at “Walkaway U” are working on technology that enables a form of digital immortality. The walkaways plan to distribute this tech as open-source software. Anyone who can build a brain scanner and cobble together enough computing power to run a simulation of a deceased friend would be able to grant that person a form of life after death. This is a scenario that the zottas desperately want to prevent; they would rather restrict access to the technology and choose only to immortalize themselves and paying customers. Their motive is not just to capture profits from the technology; the prospect of leaderless, moneyless, crowd-sourcing communes developing technology more powerful than the products of the default economic system poses an existential threat to the idea that the leaders of that system attained their position through merit alone and thus deserve to control life and death. If cooperation can beat relentless capitalistic competition at its own game and achieve technological immortality first, why would anyone continue to believe that a competitive, predatory system is the best way to advance human knowledge and wellbeing? That’s an argument you actually see today on Internet forums devoted to bitcoin, blockchain, and citizen science.

Anyone who can build a brain scanner and cobble together enough computing power to run a simulation of a deceased friend would be able to grant that person a form of life after death.

I enjoyed the way Doctorow takes today’s Internet slang and gives it slight twists that subvert the meaning. When these characters speak of “special snowflakes,” they aren’t denigrating the easily offended; instead, the “special snowflake” of Walkaway is someone who has bought into default society’s toxic notion that the elites earned their position solely by merit. The characters most frequently wield the term not against rivals but against themselves, as a way of resisting the temptation to keep score.

The zottas take what they want and program their self-driving stretch limos to speed and weave through traffic, believing that if they don’t game the system, someone else will, at their expense. “Exploit others before they exploit you” becomes their foundational virtue. As one character describes a zotta: “His whole identity rests on the idea that the system is legit and that he earned his position in it fair and square and everyone else is a whiner.”

But those so-called whiners develop real power in Doctorow’s imagined utopia, as technologies developed by the capitalist system are repurposed by the cooperative masses to reveal the system’s hypocrisy.