Mushrooms are waiting for their moment in medicine.

Every one of us will receive a handful of messages that change our lives forever. The latest for me came from my mother last September.

“My scan shows the pain in my lower back is because my cancer has spread to my adrenal glands. They are taking me off immunotherapy. I start chemo on Wednesday.”

Time slowed down. I felt dizzy, and cried. I took many deep breaths, went to the gym for hours, smashed weights, and tried to hold it together. Didn’t work. I went home, ate mountains of filthy carbs, and still no reprieve. Didn’t work. I cried. I cried some more. It felt like the end.

My mother was diagnosed with inoperable terminal lung cancer in February 2019. Small cell carcinoma, stage 4. Prognosis: one to two years to live. I thought I would never smile ever again.

Then her oncologist informed us that my mother was a good genetic match for the immunotherapy drug Keytruda, a form of immunotherapy that came out of Nobel Prize-winning research that allows the body to “recognize” cancerous cells, which normally “hide” from the immune system like enemy spaceships behind deflector shields.

Within a month my mother began to gain weight, the color returned to her cheeks, her appetite returned and so did her energy. My own mood boomeranged from despair to optimism, and it seemed she could survive for more than a couple of years. Scans later showed that Keytruda shrank her lung tumour by a whopping 60 percent, an outcome so phenomenal her oncologist clapped his hands in delight.

Things were going well, but then last summer she began to suffer constant aching back pain, which at first we thought due to inflammation (a common side effect). When the next scan revealed the cause to be a secondary growth of metastasized cancer on her adrenal gland, all my hope evaporated once more.

Unfortunately, immunotherapy drugs are designed to target to specific organs, so while Keytruda could heroically shrink the tumors in her lungs, it is not able to curb all other cancerous growths elsewhere.

Thus we were forced to leave behind the revolutionary treatment that had brought my mother back from the brink and start her instead on old-fashioned chemotherapy. Just a single round of chemo left my mother so weak, so sick, and so miserable, she texted me simply this:

“I now think the point of chemotherapy is to make death a more appealing option.”

She decided to quit after that one dose, and I supported her. Why flatten your immune system with poisonous chemicals in the middle of a global pandemic, especially if your cancer has progressed too far to be eliminated entirely anyway? If we had any hope that chemotherapy would cure her, I would have pressed my mother to soldier on. But when a lethal respiratory virus is running wild—and we live in the U.K., also known as “plague island” by the rest of the world—why make yourself more weak and more vulnerable, as well as bloody miserable?

She quit the chemo but continued with morphine, taking doses four times daily for the pain—testimony to just how much my mother was suffering. She is so averse to pharmaceutical painkillers (even acetaminophen), she gave birth to two children without an epidural and spent her entire life coping with any form of physical pain without anything but the occasional local anesthetic—including a broken femur and endless rounds of dental surgery.

The morphine alleviated her pain, but the side effects were unbearable—for both of us. They wreaked hell on her digestive system, as all opioids do. But worst of all, mood swings like I’ve never seen. My mother has been accurately described as the least moody woman in the world. Yet after just two days of liquid oral morphine, she snapped at me and exhibited dark thoughts like never before.

I figured this was it from now on: a slow decline as her cancer spread, coupled with intestinal misery and psychological darkness. I steeled myself, remembering that this is how many people end their lives. So it goes.

But then I spoke to my friend David Satori, a researcher at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in London, who has a special passion for mycology: the scientific study of fungi. He told me about people taking mixtures of medicinal and culinary mushrooms in tinctures and teas for chronic pain: chaga, reishi, turkey tail, and shiitake. All have been used traditionally for thousands of years in a variety of cultures for a variety of reasons, some of which are now being explored by Western scientists.

“What’s great about this suite of medicinal mushrooms is how deeply embedded they have been in different cultures around the world,” Satori told me. “Now, not only do they have increasing scientific validation through numerous human clinical trials, but they also have historical validation of their safety—as opposed to many novel synthesized drugs.”

I figured: couldn’t hurt. My hippie mom has always loved herbal remedies, so she wouldn’t sneer at this.

She started taking a mixture of mushroom tinctures in October 2020, and after several days, she tapered her morphine doses from four a day to one, and then after three weeks, she reduced to zero. And she stayed that way, pain free, morphine free, for months.

Mycophiles and mycophobes

If the pain relief wasn’t enough, the plot thickened when a meeting with her oncologist three months later revealed her cancer had not spread since September. Placebo effect? We like to think not.

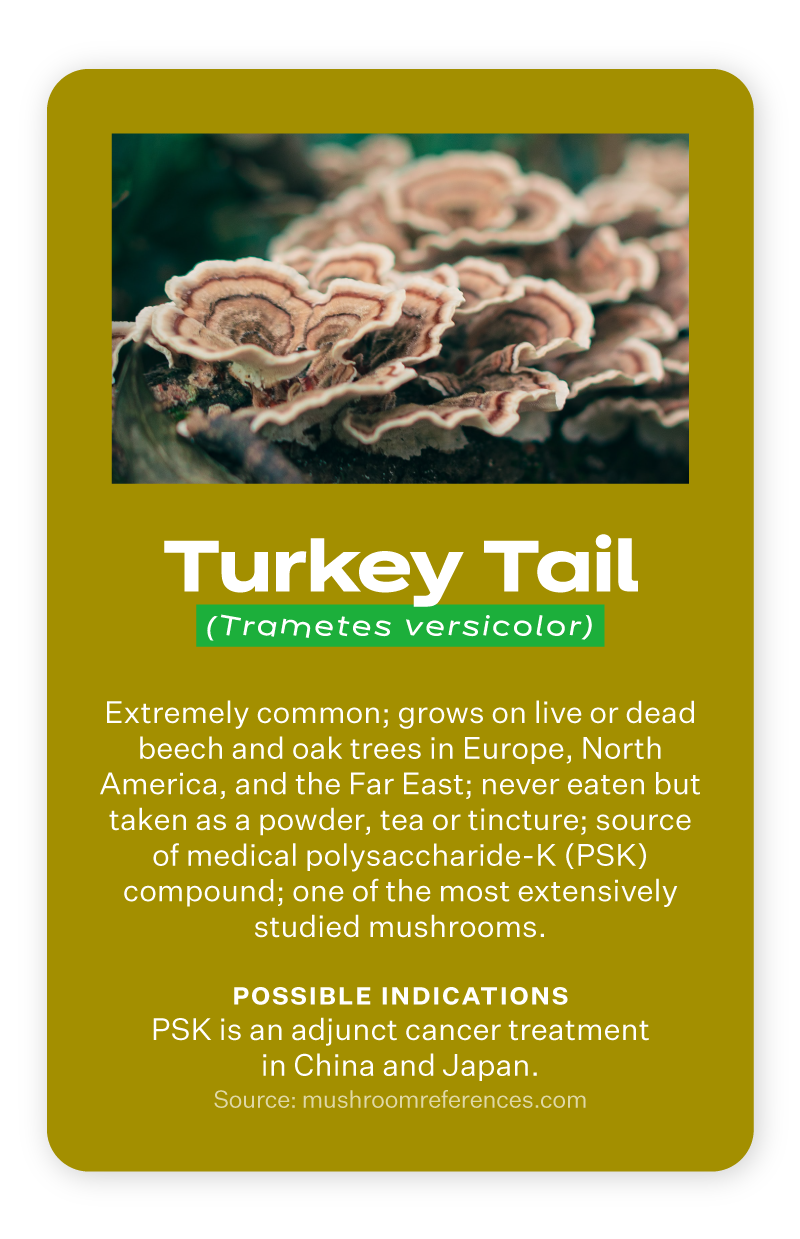

I will be the first to admit that our experience does not prove medicinal mushrooms put a brake on her cancer or alleviated her pain. But it’s clearly plausible that they did her some good. This deserves more scientific scrutiny than what the field is currently granted—which is surprising considering medicinal mushrooms have been central to traditional Chinese medicine for thousands of years, and today are regularly prescribed as an accompaniment to chemotherapy, radiation, and other standard cancer treatments in Japan and China. Large-scale long-term studies in Japan and Taiwan—including a 1994 study of 262 gastric cancer patients, a 2005 meta-analysis examining 1,094 colorectal patients, and a 2007 meta-analysis covering a staggering 8,009 gastric cancer patients—have consistently found that adding extracts such as PSK (a complex polysaccharide extracted from turkey tail fungus) increases the effectiveness of chemotherapy and extends lifespan post surgery.

Mycologists say all of the world’s cultures can broadly be defined as mushroom loving—“mycophilic”—or mushroom fearing—“mycophobic.”

Yet Western science still has barely glanced at them—even in alternative health circles. “Mushroom medicine was never part of any of the herbal apprenticeships I undertook—mushroom medicine is generally put to the side and seldom discussed,” says Anna Sitkoff, a naturopath in Washington state, who catalogs exhaustive guides on the chemical constituents of wild mushrooms and how to extract them on her website Reishi & Roses.

One reason for this, she thinks, is “mycophobia”: fear of fungi. Mycologists say all of the world’s cultures can broadly be defined as mushroom loving—“mycophilic”—or mushroom fearing—“mycophobic.” Mycophiles include the ancient Aztecs, the Sami people of Finland, a variety of indigenous cultures in the Amazon rainforest, and modern day people in China, Korea, and Japan. Mycophobes mostly include Western Europeans—the English most notoriously. “We have more fear of mushrooms in the West—we are raised to see them as something that is likely poisonous or fatal, rather than as potential food or medicine,” says Sitkoff.

While Western scientists have failed to appreciate their potential, Western social media stars have filled the void: “On Instagram you can find accounts for all the new powdered mushroom extracts, all turning them into a new superfood fad rather than powerful medicinal substances—instead of researching them, people are already jumping the gun and turning them into a lifestyle brand,” says Sitkoff.

And this is the problem: While there is an abundance of breathless medicinal mushroom evangelizing readily found on social media and influencer blogs, there is still an unfortunate dearth of rigorous clinical studies with real human patients providing sufficient evidence to justify the hype. Throw in the flaky buzzwords of wellness products—“functional food,” “neutraceutical,” “nootropic,” and the very worst, “superfood”—and scientists are even less inclined to take the sector seriously.

This combination could lead to unfulfilled expectations, disappointed customers, a burst bubble, and the ultimate failure of the industry to deliver the medical benefits to the people that could really use them—which is, theoretically, every human on Earth, given that all studies point to a general ability to support the immune system.

“My greatest fear is that many of these new companies are growing what they call ‘mushroom products’ in large batches with little quality control, selling them for a lot of money to people who are actually very sick but being given false promises,” says Sitkoff. “The amounts of beneficial compounds in a lot of these teas and supplements are not remotely equivalent to the amounts used in clinical studies. I suspect what a lot of people might be experiencing will be simply a placebo effect.”

However, the “mushboom” could be good for science, she adds. “Hopefully one positive that can come from the boom is that more money could be given to scientists who want to conduct real clinical research, because the hardest part is just doing the basic research—the reason why there are not a lot of clinical trials is because people just can’t get funding for it,” says Sitkoff.

And as long as scientists struggle to obtain funding for large and meticulous studies, wellness gurus and flash-in-the-pan startups with little scientific credibility will continue to control the narrative. All of us should be if not worried, at the very least, irritated.

What we don’t need are more wellness industry cheerleaders. What we do need are more rigorously conducted clinical trials to show which specific species of mushroom, and which specific compounds derived from them, are effective for which conditions—and what other treatments (including chemotherapy and other mainstream medical approaches) could work best in combination with them.

Hundreds of animal experiments and test tube studies already suggest mushrooms may contain unique compounds that have the capacity to kill viruses, aid the immune system, heal the gut, combat cancer, and repair the nervous system. And dozens of clinical trials with human patients have suggested that medicinal mushroom extracts can aid chemotherapy, improve cognitive performance, treat diabetes, combat hepatitis B, increase life expectancy for people with cancer, and more. But the sum total of clinical studies is paltry in contrast with the hype. And nearly all clinical trials come from either China or Japan—which Western doctors remain reluctant to read, let alone consider.

Though the evidence may not be considered sufficient by the American Medical Association, Beverly Hills and Silicon Valley have certainly taken notice: Countless enthusiastic startups (and existing supplement companies) are jumping onto the scene to sell teas, pills, chocolates, and more. A 2018 report from the market research firm Technavio forecasts growth for the medicinal mushroom sector at $13.88 billion between 2018 and 2022 (39 percent of that in the Americas alone), with annual growth at 9 percent year on year. Chicago-based firm SPINS found similar trends, with sales of reishi alone increasing 42.7 percent from May 2018 to May 2019.

Mushrooms are positioned as the new megatrend in the wellness industry: When Meghan Markle plans to endorse a range of mushroom lattes, you know things are going big time.

But when many of the best-known mushroom proselytizers have financial stakes in the outcomes of their efforts—such as Fungi Perfecti’s founder Paul Stamets (the widely acknowledged elder statesman of the field), Gavin Escolar of The Chaga Co., and Tero Isokauppila of Four Sigmatic—it’s hard to take everything they say at face value. And when wellness celebrities with zero medical or biological credentials get into the game—such as Joe Rogan endorsing Four Sigmatic as “fucking slick” with his trademark folksy gym-bro vernacular, or Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop confessing to being overcome by “mushroom-powder mania”—it’s even easier to dismiss medicinal mushrooms as nothing more than hyped-up exotic imports designed to implore naïve Westerners to open their wallets.

Especially when sweeping claims make it seem there’s nothing fans believe mushrooms can’t do, from repairing neurons and preventing Alzheimer’s to healing the intestines, recalibrating the microbiome, fortifying the immune system, and—of course—combating inflammation, the new bogeymen of complementary medicine. But such grandiose ideas risk failure because they are not backed up by enough large-scale clinical studies that test such a wide range of extremely bold claims. And where you can neither prove nor disprove a claim, charlatans prosper.

What’s really needed are large-scale clinical studies with human subjects. And those are expensive and complicated, involve mountains of paperwork and months of bureaucratic negotiation, costing millions of dollars, requiring partnering doctors, patient recruitment, review boards, statisticians and other experts to analyze the results, plus the willingness to swallow the whole expense if the trial is a failure.

But if medicinal mushrooms are to be evaluated for their true potential, this is what all mushroom enthusiasts, and especially entrepreneurs, need to push for—and pay for—long-term, rigorous, clinical studies.

Biological dark matter

“Medicinal mushroom” is slightly misleading, as many of the species aren’t technically mushrooms, but members of the much broader kingdom of fungi, which includes molds, lichens, yeasts, mushrooms, and toadstools. A “mushroom” is simply one part of a much larger fungal organism, most of which grows beneath the earth or within the hearts of trees: the mycelium, a huge branching network of thread-like structures that is not so much the root of the fungus as the heart, guts, and brain all in one. The mushroom is simply the sexually reproductive portion that pops up above ground, often only at certain times of year.

When people think “mushroom” they think of a jaunty Super Mario-type shape, but many of the species being used medicinally would never be called a “mushroom” by the average person, such as turkey tail and reishi, which look like little wooden flanges erupting from the sides of trees, or chaga and black hoof, which both resemble “tree burls” (a sort of arboreal ingrown toenail), or witch’s butter, a striking orange mold. Likely in the West we’ve embraced the term “medicinal mushroom” as the word “fungus” conjures visions of rot, disease, and death—but we have far more reason to embrace fungi rather than fear them.

“Until recently, mycology has remained in our collective blind spot—people aren’t as familiar with fungi as they are with plants and animals, and that’s reflected in our school curricula too. In fact, fungi weren’t recognized as a separate kingdom of life until 1969, the same year humans first took steps on the moon,” says Satori. “Now we’re seeing a new generation of mycologists enter the scene with an increased interest in solving some of our biggest problems. Mycology was once a neglected megascience, but now is it’s time to shine.”

Why? For starters, fungi are not actually plants, but an entirely separate kingdom of life—one that is actually more closely related to animals than plants are. On a cellular, chemical level, we can truly be described as kinfolk with fungi.

Moreover, the fungal kingdom is far older than either plants or animals—they diverged from the rest of life 1.5 billion years ago, while animals appeared around 800 million years ago, and land plants sprung from the tree of life 460 million years ago. Fungi therefore have had a much greater span of time to tinker, experiment, and evolve into a vast array of forms. It’s simply a matter of mathematics.

Yet we have only identified six percent of species of all fungi, out of an estimated 2.2 to 3.8 million total species. Consider that the International Union for the Conservation of Nature has only evaluated 343 species of fungi for their conservation status—compared to over 43,000 species of plants and 76,000 species of animals.

Mycologists describe the fungal universe as “biological dark matter”—the bulk of life on Earth, largely unexplored and unappreciated despite it being all around us, permeating all our lives in thousands of ways.

Fungi are Earth’s chemical code breakers.

Recall the antibiotic that changed the world—penicillin—is derived from a mold, and our modern pharmaceutical pantheon contains many fungal-derived life-saving drugs, such as cyclosporine and asparaginase. Fully 25 percent of the Nobel Prizes in physiology or medicine have been awarded to discoveries that involved the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Today 60 percent of all enzymes used in industrial chemical processes are generated by fungi, and 15 percent of all vaccines and therapeutic proteins are produced by engineered strains of yeast.

“Fungi live by completely different survival strategies to plants and animals—studying them is like studying alien life,” says Satori of Kew Gardens. “Each time I learned something new about them, my understanding of how nature works underwent huge transformations.”

While mushrooms never evolved some of the flashier qualities of feathered animals or flowering plants, they have one particular skill: chemistry.

Fungi are Earth’s chemical code breakers. All living things accomplish clever feats through molecular shuffling, but it could easily be argued that fungi surpass them all. It was only through symbiotic relationships with fungi that plants were able to colonize dry land, followed by all other life forms: For millions of years plants relied on fungal mycelial networks to extract nutrients and water from the land for them, before they evolved root structures of their own. If plants had not made friends with fungi, we ourselves would not exist. Millions of years later, when the world became smothered in dead trees, it was only when fungi developed the capacity to digest lignin (the structurally rigid component of wood) that the landscape could be renewed. It is thanks to fungi that we are not drowning in dead bodies. Nature’s nimblest recyclers, fungi degrade both rocks and living matter into soil, making the continued existence of life on earth possible.

Today new species are identified almost yearly that possess the ability to perform phenomenal biochemical tricks: In 2017 scientists discovered in a Pakistani landfill a new form of fungus, Aspergillus tubingensis, that had evolved the ability to digest plastic, raising possibilities for new solutions for the world’s solid waste crisis. In 2011 a form of yeast, Candida keroseneae, was found thriving in jet fuel tanks. In Japan, the matsutake mushroom claimed title as the first living thing found growing in Hiroshima after the city was devastated by the first atomic bomb in 1945. And last year NASA announced it would investigate Cladosporium sphaerospermum samples from Chernobyl, which have the ability to use radiation as an energy source, to explore their potential as shields to protect astronauts in space.

These “metabolic wizards” comprise a tragically underappreciated kingdom of life, says Merlin Sheldrake, a mycologist from Cambridge University and author of the 2020 book Entangled Life. All we need to do is take a closer look, and their world abounds in chemical riches. “There is huge potential for pharmaceutical companies to isolate new medicinal compounds from fungi,” says Sheldrake.

The Mushboom

Most credit eccentric entrepreneur and renegade mycologist Paul Stamets with igniting the spark that set the modern mushboom in motion. His 2008 TED Talk “Six Ways That Mushrooms Can Save The World” has been viewed at least 10 million times, one of the first TED lectures to go viral. (Or, as he likes to put it, fungal.) In a follow-up talk in 2011, he laid bare his mother’s breast cancer, and how extracts from turkey tail, given in combination with chemotherapy and targeted therapy drugs such as Herceptin, brought her back from death’s door.

“The same pathogens that afflict us often also affect fungi—so the natural defenses of fungi can greatly benefit human health,” argues Stamets, who has sold mushroom home remedies through his company Fungi Perfecti since 1980. Proving his point, Stamets published a study in the high-profile journal in 2018 demonstrating that extracts from Ganoderma resinaceum, also known as reishi, fed to bee colonies led to a 79-fold reduction in deformed wing virus and a 45,000-fold reduction in Lake Sinai virus in the insects—suggesting mushroom extracts hold promise for treating both colony collapse disorder in bees as well as human health.

“A consortium of molecules selected through evolution have given us a repertoire of natural remedies to fortify the health of our own species—the same extracts I cultivated for the bees are now being found to be helpful in the lab with human cell lines in reducing infection from swine flu, bird flu, hepatitis, and pox viruses,” he says. And he thinks it makes perfect sense.

“The immune systems of land animals are influenced by the wood decomposing fungi of forestlands—which is why as we deplete the natural immune systems that give us support through activities such as deforestation, we impact the immunological systems that support our own health.”

His logic is appealing. But is his reasoning solid? In the past five years, hundreds of scientific studies with lab animals and cell cultures—and dozens of clinical studies—have hinted that fungi can be uniquely powerful in reinforcing human immune systems and overall health.

Extracts from Hericium erinaceus, also known as lion’s mane—a white, shag carpet-like edible mushroom that tastes like lobster—have been shown in rodent studies to have a variety of “neuroprotective” properties: It seems to alleviate symptoms of Alzheimer’s, protect the inner ear from premature cell death, decrease the likelihood of epileptic seizures, re-calibrate the microbiome of the gut, and reduce neuropathic pain. Only a handful of double blind, randomized clinical trials have been conducted—all of them from Japan dating back to 2009. The studies were small, but well worth a follow up: Lion’s mane supplements were shown to improve cognitive performance and alleviate depression—in particular in people who are elderly and in menopausal women.

Chaga, or Inonotus obliquus—a fearsome-looking parasitic fungus that bubbles in black eruptions from birch trees—has been used in Arctic cultures from Alaska to Finland for thousands of years for gut ailments and the immune system. Despite having one of the longest traditions of medical use, this is possibly the least studied of all medicinal fungi. There have been no clinical studies with human patients in the modern era—just a handful of studies from Russia and Poland between 1959 and 1981 that suggested a potential to treat psoriasis, pain associated with peptic ulcers, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Turkey tail, or Trametes versicolor, on the other hand, has been the most widely studied of the mushrooms, as “polysaccharide K” (or PSK) has been given as standard to chemotherapy patients in Japan for four decades, giving us a huge pool of data upon which to draw—such as the previously mentioned meta-analysis covering over 8,000 gastric cancer patients. Other small studies in Japan in the 1990s showed that people given turkey tail extracts following surgery for colorectal cancer had a life expectancy twice that of the placebo population. More recent laboratory studies with rats found that PSK even reduced the likelihood of morphine dependence and withdrawal in the animals—so it could also be helpful for cancer patients in managing their use of painkillers. Yet despite huge population studies in Japan and intriguing lab work, in the West it is seldom discussed.

Which is why Stamets created mushroomreferences.com—an unbranded, unaffiliated website that serves one purpose alone: a repository of scientific studies on medicinal mushrooms anyone can show to their skeptical doctors. “It’s just the straight science,” says Stamets.

Furthering his lifelong mission to spread the gospel of fungi, Stamets also put his weight behind the production of the 2019 documentary Fantastic Fungi, enlisting legendary time-lapse filmmaker Louie Schwartzberg to reveal the strange biology of mushrooms, which can be difficult for even biologists (including myself) to grasp. A picture after all, is worth a thousand words.

How long did the film take? Twelve years.

Buyer beware

It’s clear that our interest in the medical potential for mushrooms is only going to grow. Especially when so many people feel that Western medicine might be amazing at pinpointing agents of disease and destroying them, but terrible at helping us with our everyday wellbeing.

Herbalist Robert Rogers is an assistant clinical professor at the University of Alberta who has published 56 books on mushroom diversity, medicine, preparation, and more, most notably The Fungal Pharmacy. “The medicinal mushroom industry is poised to become mainstream, and as popularity grows, so will companies that want to take advantage of that, selling inferior products such as dried whole mushrooms simply ground up and sold in capsules,” he says. “It’s very unscrupulous—you will not be able to properly digest those or gain any benefit.”

The reason is that a class of beneficial compounds in mushrooms—water soluble complex polysaccarides known as “beta glucans”—need to be liberated from the scaffolding of chitin in the cell walls. Chitin is the same molecule contained in the hard exoskeletons of insects, and humans cannot digest it: We can only access them if mushrooms are cooked or boiled in water at a minimum temperature of 70 degrees Celsius (158 degrees Fahrenheit) for several hours (which is why all ancient cultures who used chaga, for example, would boil the wood-like fungus for hours as a tea preparation).

While we wait for more funding for clinical trials and for government regulators like the FDA to impose good quality control regulations, labeling requirements, and advertising standards, Rogers says consumers have to take it upon themselves to understand the different growing conditions for commercially produced fungi, and look for product information themselves. “Look at the percentage of ‘fruiting body,’ the mushrooms, versus mycelium in the product— a lot of growers produce mycelium on grain, rather than fruiting bodies grown on substrates including wood,” he advises. One could liken mushrooms grown industrially on sacks of grain to hothouse tomatoes: still decent enough to eat, but nowhere near as colorful or flavorful as field-grown tomatoes.

He also advises understanding the chemistry of mushrooms, and looking for the sum total content of beta glucans on a product label—if the label only lists total “polysaccharide” volume and not “beta glucans” specifically, it’s likely of poor quality, he says.

“Almost every product you see if you search on Amazon won’t be honest about what’s being sold to you,” agrees Satori, who points to the company Kaapa in Finland as his favourite medicinal mushroom brand. Kaapa harvest all their mushrooms either from the wild in Finland (a country renowned for meticulous management of its forests) or from their “forest farm” where mushrooms are grown on a vast collection of 20,000 logs, and never on sacks of grain. It takes longer than simply churning out mycelium on sacks of grain, but it produces higher quality products, they argue.

“We spend a lot of time trying to understand how these mushrooms behave in their natural environment, so we understand the optimal growing conditions for our farm,” says American Joette Crosier of Kaapa, who relocated from her native West Virginia to Finland because they were so far ahead of American mushroom companies in their diligence, she says. “Look at shiitake: If they’re grown in a really healthy natural environment, they develop beautiful cracked caps on top. They don’t look like that when mass-produced. So we grew this species on our farm, experimenting with different conditions, to try and replicate that ideal natural environment.” It takes more time, she says, but they are confident their product is of higher quality.

“We are at the beginning of a very, very exciting phase for medicinal mushrooms.”

There are plenty of snake oil salesmen around, but Rogers is confident the future is bright. “Currently 90 percent of the world’s medicinal mushrooms are produced and grown in China, and there are significant problems with that in terms of heavy metal content, organic certification, and more. But I think things will change as more companies in Europe and North America start to produce high quality, pristine, organic products—and people will have to decide what to buy based on their pocketbook. So things will shake out. We are at the beginning of a very, very exciting phase for medicinal mushrooms.”

As a biologist who worships the complexity of living things but hates the wellness industry and all its self-involved vacuousness, I couldn’t agree more. Even if I hadn’t seen medicinal mushrooms relieve my irreplaceable mother from pain or freeze her lethal cancer in time, the biochemistry of this huge, strange, and genuinely mind-bending kingdom of life would be enough to convince me.

As for my mother, I have no delusions that medicinal mushrooms will cure her. I like to remind my hippie mom at every opportunity that it was a highly sophisticated lab-generated form of Western medicine that shrunk her tumors by 60 percent—I don’t think any mushroom combination on the planet could have done that. But we have every reason to think that a good combination of medicinal mushrooms can hold her steady for at least a few more years—and maybe then another new groundbreaking Nobel-winning pharmaceutical will be available to keep her with me a few more years yet.

In the meantime, I’ve decided not to begrudge the wellness industry cheerleaders too much, because if they hadn’t banged on about the benefits of mushrooms in the vacuum of proper scientific studies, I might never have heard about them in the first place—and just maybe, neither would you.