This eclectic mix of researchers is exploring off-Earth living in radical new ways.

“JJ, can you please clear that stuff out of the engineering bay and the airlock?” she yells.

Michaela Musilova is shouting instructions to her crew through raging gusts of wind and flying dust. The team is disembarking their “shuttle” in the mid-September heat and unpacking their equipment after a bumpy takeoff from “Earth” for a landing on “Moon.” The team is preparing to bunker down in a simulated lunar habitat for two weeks, entering into a new “analog” astronaut mission, a not-so-down-to-Earth experiment on the cutting edge of human extraplanetary exploration sometimes called a space simulation.

The Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) habitat is on the edge of Mauna Loa, an active volcano. It is a big, white, geodesic dome hooked up to an array of solar panels and a few smaller huts on a high, dusty, isolated volcanic plain, surrounded by lava flows and little else. The nearest emergency services are an hour away by car, and all communications are set with a latency intended to mimic the standard three-second delay astronauts on the moon would experience. The crew has no regular access to the internet while they’re on the mission, and if they need anything, they email “mission control,” an on-call team of volunteers assisting the HI-SEAS operation on “Earth,” down the slopes of the volcano.

The mission is unusual not just for its earthbound emulation of life on distant planets—but also this time for its funding. It’s one of a handful of independent research trips to the site that’s not part of a federally-funded NASA program and not run by the University of Hawaii, which operated HI-SEAS for years. Instead, the trip is facilitated by the site’s new operator, the International Moon Base Alliance—an organization founded and chaired by the millionaire Henk Rogers, who also founded the energy non-profit the Blue Planet Foundation.

Musilova and her mission crew of “analog astronauts” aren’t the Captain America-style former military fighter pilots and physicists you might expect to find in space research simulations. Instead, the crew is made up of artists, tissue engineers, and synthetic biologists brought together through one shared goal: to democratize space research.

So much of the biology and human factors research that we will likely end up needing to do because it will be so crucial to off-Earth living, whether on the space station, the moon, or Mars, hasn’t been done yet. Science is still very much at the beginning of a high mountain of research on the ways human life in space and on other satellites will need to evolve, and the science involved will be rooted not so much in rocket ignition fluid mechanics and Newtonian gravitational dynamics as advancements in growing genetically modified food, team psychology, and tissue engineering.

By opening this door, analog programs like HI-SEAS are creating opportunities for democratizing space in which independent researchers unaffiliated with universities or government research programs can work together across disciplines on projects that are too speculative, too weird, or too small for a federal agency to fund.

With their eyes trained up to the skies and off to the horizons of human life elsewhere in the galaxy, independent researchers see analog simulations as the perfect testing ground for pushing the envelope of what space research looks like.

Space is not just for astronauts

Jaden “JJ” Hastings, the vice commander of the Selene I crew, is an artist and synthetic biologist who was the first biohacker in Australia to have a biosecurity-certified home lab. Selene I (the mission run by Musilova) was Hastings’s second time in the HI-SEAS habitat, but she is old hat at analog missions, having done stints at similar facilities in Antarctica as well as at Lunares, an analog base in an old military hangar in Pila, Poland. There she worked with astrobiologist Sian Proctor (now a member of the SpaceX civilian crew) on a 2018 study of the microbiome population within the habitat.

Thirty-something-year-old Hastings is a striking person. She’s nearly six feet tall and has long, bright, dyed-orange hair, and she often fashions it into an elaborate, loose bun on the very top of her head, making her seem five inches taller and giving her a slightly punk vibe and spilling fire-colored tumbles around her head. Outside her job at Weill Cornell Medical School, where she’s a fellow in computational biomedicine, Hastings operates Sensoria, a program that organizes analog research missions that prioritize applications from women and non-binary early-career researchers.

I should add that I know Hastings socially. We have attended the same conferences for years, and our social circles overlap. Through my reporting on the insular world of biohacking, I know JJ to be something of a big fish in the small pond of the biohacker community. She’s a radical thinker and a passionate, collaborative scientist.

In interviews for this piece, Hastings explained the mission for her company, saying that one aim of the Sensoria program is to widen the focus of scientists working within the global network of analog habitats.

HI-SEAS is just one of a global network of terrestrial research groups looking at problems like how to grow fresh food in a tiny habitat, as well as considering the cultural, ethical, and spiritual aspects of what it will take for human life to flourish in space.

For example, what happens when someone dies on another planet? How will people create sacred spaces and find time for spiritual connection on a mission to Mars? What happens to people when they are trapped in the dark for months? How should habitats be constructed?

Henk Rogers, the millionaire video game creator-turned-sustainability entrepreneur who is famous for popularizing Tetris, has managed HI-SEAS since 2012. He wears his silver hair in a short, slicked-back ponytail. Beneath a graying beard, he is almost always pictured wearing some kind of carved amulet around his neck and looks… well, he looks like he lives on an off-the grid, eco-friendly ranch in Hawaii. His involvement with a handful of citizen-led and nonprofit space initiatives led to founding the International Moon Base Alliance (which aims to unite a network of space research groups), and to building HI-SEAS back in 2013, originally in partnership with NASA and the University of Hawaii. Since a couple high profile NASA missions to the site ended dramatically and the NASA funding expired, the Moonbase Alliance has invited a myriad of groups to examine questions that may be too nebulous for a federal agency with strict congressional mandates.

Shortly after NASA’s financial involvement with the site ended in 2019, Rogers brought on Musilova, who had been crew on some of the NASA-funded missions as a researcher, as the director of its analog program. She now aims to use the habitat to host some truly radical independent scientists with self-funding and big ideas, and she works with teams to make sure the experiments are relevant to space research.

Much of the world’s analog space exploration research is a mixture of academics and independent researchers, with funding from traditional sources like government grants and philanthropic donations. But each different project has a somewhat specialized research focus, and almost all of them are led by passionate people who have devoted their lives to democratizing space research.

“Space is for everyone. It’s everyone’s frontier,” says Hastings.

The Haughton–Mars Project, based in a crater in an Arctic island in Canada, researches geology and robotics for Mars exploration. Meanwhile, the research stations run by the Mars Society have two elaborate analog habitats, one in Utah and the other also in northern Canada. Some projects, like Lunark (on a glacier in Greenland) and D-Mars (in the Negev desert in Israel) combine synthetic biology with experts in art, architecture, and design, in an effort to democratize the evolution of off-Earth research. Musilova is enthusiastic about all of this.

“I want to open up [the facility] to other space agencies, other organizations, and other people not affiliated with space agencies,” says Musilova, a 31-year-old Slovakian astrobiologist with CV credits at NASA and the International Space University, who considers her archaeologist mother to be the “Slovak Indiana Jones.”

Musilova can often be seen wearing her dark sunglasses pushed up on her head to hold back her long blonde hair, and offers viewers a friendly “Aloha!” in video diaries from the habitat. She has commanded more than 20 analog missions, and says that HI-SEAS is one of the best analog environments in the world, partly because of its flexibility: it can be set up either as a lunar habitat or a Martian one.

“I’m aiming to contribute to get people to go to the moon and Mars itself,” Musilova says.

Biohack the (next) planet

There’s a disconnect between NASA’s focus on engineering and the eclectic, ambitious emerging biologists that are gathering in the analog space. They say it can be challenging to convince the powers that be inside the agency that the future of space exploration depends on adaptable systems that can grow. It’s a long shot to get funding and support for the wild ideas of interdisciplinary scientists and synthetic biologists, many of whom consider themselves biohackers and bio-artists—far outside of the peer-reviewed confines of the academic mainstream. Even the insiders agree.

“I think that we have been barely successful in convincing NASA that [synthetic biology research] is important, but not successful enough that we have a big program in it,” says astrobiologist and NASA Ames Research Center synthetic biology pioneer Lynn Rothschild.

“NASA’s goal is not synthetic biology. NASA’s goal is, ‘Let’s get the boots on the moon.’”

Rothschild is a bookish, mid-60s academic with appointments at both Stanford and Brown. She will enthusiastically chatter about space research with the slightest nudge, and her parlance becomes rapid as she grows more excited about her subject during our interviews. She is careful to point out that while NASA is probably the best high-tech agency in the world, there just hasn’t been significant interest in synthetic biology, despite other government research arms investing heavily in advancing biology for terrestrial uses. The agency has funded small projects here and there, but there are no major pushes for synbio research.

“NASA is a mission-oriented agency,” says Rothschild. “Synthetic biology is a way to fulfill those missions, and for human missions, particularly long-term missions, it is going to be an absolutely required technology. But NASA’s goal is not synthetic biology. NASA’s goal is, ‘Let’s get the boots on the moon.’”

An additional challenge for would-be space researchers is that within NASA, missions are multi-decade designs. If a creative new idea or innovation is discovered after a plan is in motion, researchers face uphill battles to convince the powers that be to change course.

“That approach is reliable and the conversations are appropriate. But [NASA missions] are now not the only name in the game,” says tissue scientist Jessica Snyder, a former researcher at Rothschild’s lab, who joined the Selene I mission at HI-SEAS with Musilova and Hastings. “People are willing to be more ambiguous and exploratory to play with the technology. Even if it doesn’t go to space, there are so many knock-on benefits to allowing us to play with things.”

Snyder says analog projects are valuable because of the opportunities for interdisciplinary researchers to inspire one another’s research, as the short missions are agile by design—ideal for anyone with a hacker mindset. Researchers can self-fund their work, fail quickly and creatively, and iteratively collaborate without needing to fight for every dime, or justify every idea to some extramural funding committee.

Sara Nejad, a biodesigner and synthetic biologist at New York University who focuses on space applications of bioart, says that analog space is an ideal playground for experimental research on the ways space habitats’ complex interconnected systems impact one another. Humans, plants, machines, and microbes all need to be studied together, with an interdisciplinary lens.

“Imagine having biohackers, artists, and designers working together on creating systems that engineers at NASA wouldn’t even conceive of because they’re so concerned with what’s practical and efficient and cost-effective,” says Nejad. “NASA is a government agency, and they have their own objectives. That’s what makes [analog researchers] unique. They’re not bogged down with business goals. It’s all about exploring and innovating.”

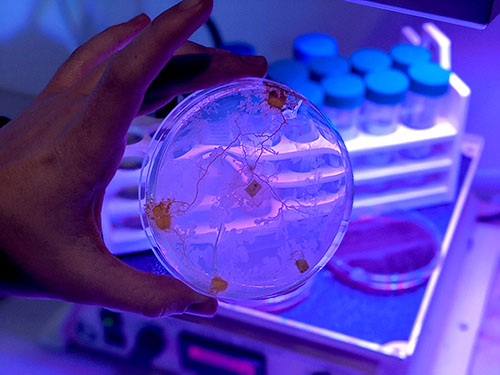

Elliot Roth, a 27-year-old synthetic biologist and CEO of Spira, a company that makes food dyes from algae, joined the Selene I mission as well. His trip to the habitat was self-funded with leftover bar mitzvah money, and his research was focused on growing algae quickly in the habitat. But he also brought a laundry list of experiments to run from colleagues and friends, not unlike the way scientists piggyback onto research heading to the International Space Station. With colleagues at Stanford, USC, UMass Amherst, and University of Rochester, Roth was engaged in psychological experiments like daily journaling, listening to nature sounds to see if it brought a sense of homesickness, and glucose monitoring, in addition to the six experiments he brought into the habitat, including growing algae on simulated human urine—just in case we need to do that on Mars.

Roth agrees that playfulness and comfort with team building across disciplines and backgrounds has been the key to the success of many of the recent missions at HI-SEAS.

The other right stuff

Historically, athletic men, mostly from military aviation backgrounds, have been sought by NASA for space exploration. But masculine bulk may not be the exact kind of body type that’s best-equipped to function in an off-Earth habitat or a long-haul journey between planets. Hastings’ second goal for Sensoria is to bring women and non-binary people into space research, which she believes will be the key to getting humans to live successfully off Earth. The capacity for empathetic camaraderie is the new kind of “right stuff” that future astronauts will need, she says, and that passion, creativity, and interdisciplinary thinking will fuel the space forward.

For its part, NASA has historically misfired when considering how space will affect the unique physiology of non-male astronauts, and a series of high-profile mistakes has been embarrassing for the agency. (It’s unclear if they have learned that women don’t need 100 tampons for a few days or that they have bodies that are sized differently than male astronauts.)

“From a practical point of view, the physiology of women is different. Women use different amounts of oxygen,” says Rothschild. “You don’t want to be in a situation where you have not planned for a woman and you’re thinking, ‘Oh they’re just small men.”

In contrast, Hastings’ Sensoria program is launching its fourth majority-female mission to the HI-SEAS base, with projects specifically focused on the ways space impacts women.

For example, one Sensoria project considers the ways the female microbiome changes when six women are stuck together in a habitat for weeks or months. Another project is testing new patterns for flight suits to make them more inclusive of body diversity and accessible across the gender spectrum.

One not-so-surprising discovery for the Sensoria crew was that compost toilets, which are widely used for analog habitats, aren’t ideal when six women are using them.

“If you have too many people using [the compost toilet] for urination, it tends to flood. The only other option was the urinal!” Hastings giggles as she explains the struggle of an all-female crew making a “behavioral change” to accommodate the inherently sexist design of the habitat. “Even the spaces themselves are not designed for diverse bodies… We have to start intentionally undoing this history,” she says.

If we’re to live as humans somewhere else, Hastings believes we need to consider how that’s going to work in a totally holistic way—for every kind of person.

Analog research into human experiences like group dynamics, death, and cultural celebrations can lay the groundwork for larger projects. The Selene I crew celebrated Rosh Hashanah and had a funeral in the habitat to explore the psychological impacts of such occasions. Collecting data and documenting emotional and psychological responses can be advantageous, says Hastings. “Doing these kinds of things pushes the conversation along for the future, even if there is no specific remit or demand for it immediately.”

It’s this passion and creative energy that will ultimately change the face of space research, say the analog astronauts. Scoring a chance to hitch a ride with NASA to ISS, or crew a manned mission, would be a dream for any analog researcher, but as the private sector ramps up and NASA’s position in the global space race somewhat shrinks, the researchers are hoping to get their work in front of newer players, like SpaceX, or other countries with burgeoning space programs.

“To live off Earth, we have to think out of the box, we have to realize that we have to adapt,” says Musilova. “We need to find new ways to grow things in space, develop medicines. All of these things [that biology is focused on] are going to open up space travel for people all around the world.”

Editor’s note: This essay was updated on 6/15/21 to clarify the relationship between Henk Rogers, the Blue Planet Foundation, and the International Moon Base Alliance.