DARPA is developing an implantable device with bioengineered cells for treating everything from traveler’s diarrhea to jet lag.

A multimillion-dollar program from the U.S. military’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is seeking to develop an “internal pharmacy” in the form of an implantable device containing a set of bioengineered cells and a small LED light that would trigger the release of specific biomolecules on demand to counter the effects of jet lag and traveler’s diarrhea—two conditions that can seriously impede soldiers’ health and performance.

“The program is trying to give the war fighter a way to control her or his physiology so that they can perform to the best of their ability, to stay healthy and alive,” says Paul Sheehan, who’s managing the project at DARPA, which announced $33 million in grant funding for a new Advanced Acclimation and Protection Tool for Environmental Readiness (ADAPTER) program in May.

If it works, scientists think the technique could help all kinds of people who have to adjust to different sleep schedules—people like graveyard-shift workers or people who regularly take medications for chronic illnesses that disrupt their sleep.

Jet lagging behind

The immediate danger of sleep deprivation on personnel is as obvious in the military as it is in civilian life. Sleepy people make mistakes. Service members who reported sleep deprivation were far more likely to be involved in vehicular accidents or sustain other injuries than those who didn’t. Outside the military, when doctors in residency programs worked continuous shifts longer than 24 hours, medical errors increased 36 percent and diagnostic errors ballooned more than five-fold. Nurses working night shifts experience similar challenges.

Traveling far during a deployment can severely impact a soldier’s performance by disrupting their sleep schedule as they acclimate to a new time zone. Of course, some pharmaceuticals already exist, but sleeping pills like Ambien can cause side effects like confusion and irregular heartbeats or just leave the users groggy the next day. Your body can only adjust about one hour per night. “So if you’re traveling eight time zones or shifting your schedule by eight hours, it would take you over a week to adjust to that,” says Jonathan Rivnay, an engineer at Northwestern University leading the DARPA project. He adds that options like melatonin can help, but only minimally. The supplement only shifts your sleep cycle one direction, making you fall asleep a little earlier, “so [whether or not they’re helpful at all] depends on your direction of travel.”

Making the most of melatonin is one aspect of the ADAPTER program, and a group of grant recipients at Stanford University will work to create an implantable device to release the supplement regularly, to help you start falling asleep earlier so your body can start to adjust to a new time zone before you travel. One of the supplement’s limitations is that soldiers have to be sure to take it at the optimal time for it to work. “You can imagine an individual who’s engaged in combat maybe is not thinking about their sleep when they’re on active duty,” says Kimberly Fenn, a circadian rhythm researcher at the Michigan State University who is not involved in the project.

The circadian rhythm is the “master clock” that regulates cellular and molecular function in our bodies around a 24-hour cycle. While the rhythm responds to cues from natural light and is frequently associated with sleep and wakefulness, the cycle does more than regulate somnolence.

When we think about time zone and travel, “we often think about the disruption to your sleep, but it also affects essentially all of your underlying physiology. Every cell in your body fluctuates on this 24-hour rhythm,” so if you travel to a time zone six hours ahead of your current time zone, it’s not just the cells involved in sleep that need to adjust. “Essentially every cell in your body needs to shift these six hours,” says Fenn. Forcing those cells to shift their functioning can cause long-term problems. “If you just take a rat and make it shift [its sleep cycle] six hours every week, those rats die earlier than if they don’t have to shift.”

Research involving people who engage in shift work, such as nurses, has shown that it can lead to all sorts of health problems, says Fenn, “including higher rates of obesity, high rates of diabetes, higher rates of cardiac issues, heart attacks, high blood pressure.”

The military wants to do more than help soldiers sleep a bit easier. It wants to make their whole physiology better. Rivnay explains that, “you might be shifted to the light, dark cycle, but your feed cycle is not shifting accordingly. And so now you have this mismatch in the various performance and health issues.”

How it would work

Researchers believe that 60 percent of service members sleep less than six hours per night.

The military has been investing in research to improve sleep. Proposed solutions include “tactical naps” and transcranial electrical stimulation—electrically stimulating neurons through a swim-cap-style hat or headband—aimed at helping soldiers fall into a deep sleep faster.

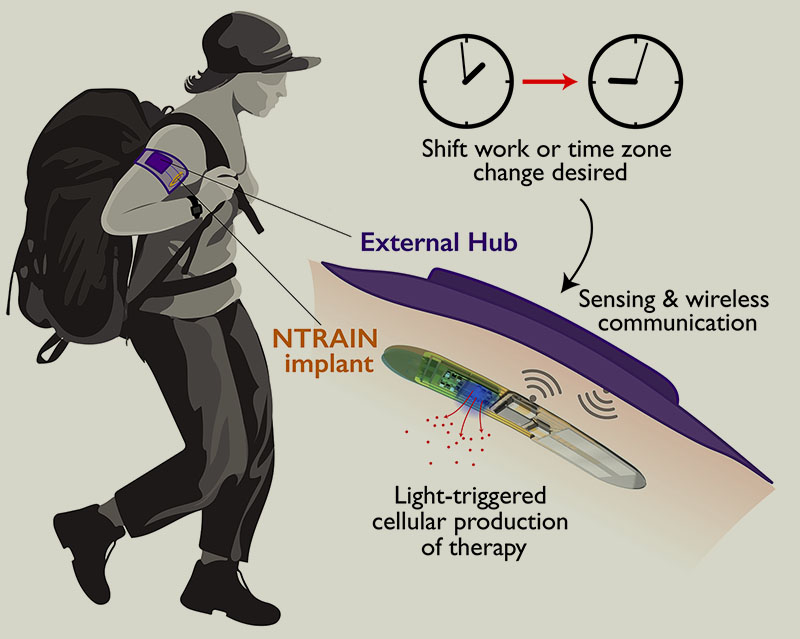

The new DARPA project looks to develop something far more sophisticated over the next four and a half years by creating and testing the wireless ADAPTER device containing cells engineered to release certain proteins that could modulate your circadian rhythm in response to an embedded LED light that users could program with the push of a few buttons on their smartphones. The light would turn on and off according to the schedule you’ve set, stimulate the production of the necessary molecules precisely when you need them, and you would be able to change your dose by adjusting the intensity or duration of the light, says Rivnay. Since the cells could produce the molecules, you’d never have to “refill” them. In order to keep the cells alive, the researchers plan to develop a membrane to house them, which will allow for the exchange of oxygen and other nutrients while guarding against immune cells that could attack the cells in the living pharmacy.

The technology of engineering cells to respond to light, called optogenetics, has already been used to control all kinds of cells in animals to study processes like addiction. “Anything that your cells can produce, you can theoretically engineer cells to produce on demand,” says Rivnay.

Over the past several years optogenetics has given scientists the incredible ability to control cells in living animals. Using the technique to manipulate cellular activity has led to major insights into both biology and behavior. Scientists have also used optogenetic neurons, for example, to create cellular electrodes that could act like wires into the brain to electrically stimulate neurons to function. These wires mimic metal electrodes currently used in deep brain stimulation—a procedure in which the metal electrode is implanted into a patient’s brain where it stimulates cells to produce dopamine to treat Parkinson’s disease.

He declined to specify which molecules the cells he’s working on will release, but he says they are testing several, all of which were chosen because they’ve been studied in Petri dishes or animal models. The team hopes that with a bevy of different molecules, an internal pharmacy will be able to control multiple aspects of a person’s circadian rhythm and have a larger impact than just adjusting sleep. In the first phase of the project, one goal is to be able to line up sleep cycles with feeding-fasting cycles, for instance. “The big question mark is whether the biomolecules we’re choosing will have the intended shifting effect,” Rivnay says.

The second engineering hurdle will be in finding ways to integrate those cells into the living pharmacy devices they’ve imagined. Sheehan emphasizes that, of course, nothing will be given to a soldier before it’s been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

In addition to being able to stimulate the production of certain molecules within the body with a beam of light, the team hopes to make the technology programmable, explains Sheehan. If, for example, you know that three days from today, you’re being deployed to a location six times zones away from where you are now, you can program that into the device and initiate therapy in advance. The “pharmacy” would start to release molecules to help you adjust to the time zone change, basically having your body travel in that direction before you even got on the plane, he says.

This could make taking certain drugs for chronic illnesses a passive action that people would no longer have to think or worry about.

A similar technique would be used to battle traveler’s diarrhea. A team at MIT is developing a programmable device that could be swallowed before traveling. If a solider traveling to a place where the food or water might contain unfamiliar pathogens, he or she would swallow the pill-like device, which would release a prophylactic non-antibiotic therapy every few hours. Currently, soldiers would have to wait for symptoms to arise, then be prescribed antibiotic treatments.

This wouldn’t be the first pill connected to a cell phone. Scientists have previously designed a swallowed pill that temporarily monitors conditions in your digestive tract and sends information to a cell phone or computer as it travels through your digestive system. But in that case, the pills only send information about the presence of medication in the stomach—the user cannot trigger them to release medication of their own.

Beyond the soldiers

The stated purpose of the program is to help soldiers perform optimally, but the researchers involved are enthusiastic that the project’s findings could have implications for all fields of medicine. An implantable device like this could make taking certain drugs for chronic illnesses a passive action that people would no longer have to think or worry about. It could optimize the timing of doses and prevent any from being missed.

Additionally, there’s an entire field of science called chronotherapy—the study of how delivering treatments at different times can affect their outcomes—that suggests widely different health outcomes based solely on when people take prescribed drugs. This device could be the ultimate chronotherapy tool by programming it to deliver therapies at exactly the right time, even when a person is sleeping.

“The classic example is for cancer,” says Sheehan. “It is known that the best time to give many cancer treatments is when patients are asleep,” because the treatments target rapidly dividing cells. When the patient is asleep, many healthy cells that divide rapidly when they’re awake take a break, so giving the therapy while the patient sleeps could reduce its side effects. “But that doesn’t fit in with when the doctors and the nurses are available.”

For someone who needs insulin to control diabetes, the device could act as an insulin factory that never needs to be refilled or replaced, explains Rivnay.

“The implications of an implantable device that can deliver therapy on demand are huge,” says Sheehan.