SERIES

The Champion for Rare Disease Cures

An entrepreneur with his own rare disease finds a way to align incentives and needs to support research on rare diseases.

This is the fifth story in a series.

In October 2019, Onno Faber made the familiar drive from San Francisco to a specialized clinic in Los Angeles to lie down on a gantry and slip his head inside the giant white tube of an MRI machine. He’d been making the trip every three months for about five years, to glimpse the tumor growing on his right auditory nerve.

For a year and a half, as Onno slugged down 40 pills a week and suffered through side effects from fever to brain fog, the tumor held steady. And within that pause Onno kept hearing through his right ear (another tumor took out his left hearing nerve years ago). He kept singing to himself in his apartment in San Francisco, retained his ability to walk steadily, balance, and ski with friends. He bought time—time to put his entrepreneurialism and his cadre of tech-savvy friends to work pursuing treatments for his rare genetic disorder and the thousands of others that receive little investment from pharma companies that prefer big markets.

The next day, the results came back: the tumor had grown 40 percent.

“Oh shit,” Onno said. Time was up.

Since his diagnosis with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) in 2015, Onno has been on a quest to defy his prognosis and disrupt the rigged game of drug development for rare diseases.

As an engineer-turned-serial-entrepreneur, he approaches his mission in the agile style of an innovator: He’ll find one solution, learn from it, use it to buy time, then let that time and that lesson lead him to the next solution. All the while, he’s racing to outpace NF2, which causes nonmalignant tumors to grow on the nerves enabling hearing and balance, and which will eventually claim the rest of his hearing and perhaps his ability to walk. It’s a journey borne of both innate curiosity and urgency, leaping from lily pad to lily pad, connecting dot to dot.

Now, his next dot is an unconventional new therapeutics company called Rarebase.

Onno, a 40-year-old Netherlands native, originally launched his quest by teaming up with friends in technology and science to sequence his tumor’s genome (one friend happened to have a gene sequencing machine in his apartment). Then he hosted a hackathon where experts from across the country searched that genome for clues to treatment. He launched a company, called RDMD, that empowers people with rare diseases to pool their data and participate in pharmaceutical research. And he started taking lapatinib, a breast cancer drug that his friends’ calculations correctly predicted would work on his NF2.

No small group with a particular genetic mutation can raise the mountains of cash required to develop a drug and take it through clinical trials.

But two years ago, the tumor had finally overcome the lapatinib. And his company, RDMD (recently renamed AllStripes), was growing and thriving and ready to run without Onno. He needed to make his next leap, personally and professionally. So he switched to taking another off-label drug called everolimus, which is not normally prescribed for NF2. And he set about starting up Rarebase with a mission to remake the dysfunctional rare disease research space.

Rarebase aims to amplify power by connecting dots. (It’s no accident, Onno notes, that he originally trained as an architect.) Families of the estimated 300 to 400 million people worldwide with rare diseases, many of them children, are all engaged in the fight of their lives on isolated islands. No small group with a particular genetic mutation can raise the mountains of cash required to develop a drug and take it through clinical trials. Plus, a second roadblock to rare disease treatments runs even deeper than money: a lack of ideas.

“That is actually the big problem for this enormous group of people with a relatively unique mutation: There is no product that they can chase,” Onno says. The more he learned, the more he wanted to attack this earliest phase of the problem. “We need to fill the top of the funnel with better ideas and better therapies in order to actually work on them.”

With Rarebase, Onno and his cofounder, biotech entrepreneur Omid Karkouti, intend to connect those islands financially and scientifically, turning many smaller problems into fewer shared problems. Their thinking is that disorders caused by different gene mutations might still have biochemical features in common. A treatment that works for one might benefit another. A new research method or technology developed for one might accelerate progress for many. And, crucially for Rarebase’s business model, the money raised to research an individual rare disease helps build the platforms that could advance research for all.

“Where are the overlaps? And where are these ideas that get unlocked if you get enough people to do it?” Onno asks. “These things don’t have to be lonely crusades, but they are. Everyone is on their own right now.”

Racing against the clock

Rarebase is researching treatments for neurofibromatosis type 2, of course—but also other rare genetic disorders, including some in which a single point mutation, one variant among 3.2 billion DNA bases, means life or death to a family.

One such Rarebase client is Kasey Woleben, who lives outside Dallas in McKinney, Texas, and who has run into almost every dead end the pharmaceutical industry can throw up. Her son Will grew healthily until around age two, when he started to stumble and fall. Countless doctor visits and misdiagnoses later, doctors led Kasey and her husband Doug into a conference room, projected slides on a screen, and told them Will had a rare genetic disorder called Leigh syndrome, which prevents cells’ mitochondria from generating the energy the cells need to survive. Will would progressively lose his bodily functions, ultimately including his ability to breathe, and he would be unlikely to survive past age 10. There was no cure, the doctors said, and the Wolebens should focus instead on enjoying the time they had with their child.

“I can still feel that sickness. I felt like I was literally going to pass out,” Kasey says. But then, “You have to pick yourself up and get through all the emotions and then you have to get a game plan, because it’s not going to happen on its own.”

Since then, Kasey and Doug have made superhuman efforts to defy Will’s dire prognosis but have hit only obstacle after obstacle. Doug wrote hundreds of emails to scientists, pharma companies, and members of congress, asking for research or money to fund it. He got a lot of sympathetic responses but received no positive replies. So the Wolebens rounded up $150,000 from family and friends and gave it to a prominent children’s research hospital for a study of potential drugs, but the researchers got no results and shared no data with them. A stem cell treatment in Panama, which cost $20,000, made no difference. Tantalizingly, an experimental drug in clinical trials held Will’s condition steady for a year and a half, but then another pharma company acquired the drug and decided to shelve it.

“You’re racing against the clock every day, and in the meantime my son’s losing his abilities very rapidly,” Kasey says. Within the first nine months after diagnosis, Will lost his ability to walk. He started having to eat through a feeding tube.

Finally, they met a researcher at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center who would try to develop a gene therapy specific to Leigh syndrome if the Wolebens could raise the $300,000 needed to do the work—which they did. “We did everything from shirt sales to lemonade stands to casino nights to GoFundMe and anything in between,” Kasey recalls. They also attracted donations from a few billionaires and poured in all the money they could from their families. The research worked, and Taysha Gene Therapies licensed the drug and plans to launch a clinical trial soon. But there is no certainty that their son will be included in the trial.

“It’s different when you’re a parent and you’re living with your child who is dying in front of you, than when you’re a company executive and you have to answer to shareholders and boards,” says Kasey. “My endgame is different than yours.”

Meanwhile, Will is nine-and-a-half years old, facing down the ominous deadline doctors gave him seven years ago. He has full cognitive function, enjoys playing Minecraft, and is saving up his money to buy a pet axolotl, an exotic underwater salamander. “I’m trying to teach him about money, because even though he is terminal I try to treat him the same as my other child,” says Kasey (a younger sister does not have the disorder). But every day she sees her son get a little weaker. His joints are stiffening. He’s aspirating on his saliva. And Kasey has turned to Rarebase.

“I want multiple shots on goal,” she says. “I cannot do just one thing. I want to try everything because the clock is ticking, and it’s not in our favor.”

Tiny, virtual biotechs

When a family like the Wolebens approaches Onno and Rarebase to research a disease, the company’s scientific advisors survey the science and choose the research strategy with the best chance of getting a treatment to patients fastest. They’re exploring forms of treatment that include gene therapy, antisense oligonucleotides (a biochemical tool for silencing gene expression), and off-label drug repurposing, searching through small molecule libraries and looking for promising biological agents like antibodies that may target some crucial molecule involved in the disease. In each case, patients themselves, weighing in about their priorities and concerns, help set the direction. The company hires outside laboratories to conduct the research.

Patients pay to launch each research project. But, charging people at less than cost, Rarebase doesn’t make money on these patient contracts—rather, it hones its technology and science through them. It aims to spin off biotech companies when it identifies a therapy promising enough for a clinical trial. Patients and their families, as investors, stand to benefit financially if the company makes a profit.

“We’re turning their efforts into tiny, virtual biotechs,” Onno explains. The scientific endgame is not just to find treatments for individual patients but to pool those smaller investments to build cutting-edge drug-development technologies that enable advances for thousands or millions more. “For most disorders that’s probably not going to happen, but once in a while we might stumble on something,” says Onno, always an optimist. The perennial question that perverts pharmaceutical industry incentives is: What’s the market for this? It’s a hard, cold question that evokes a bottom-line business reality as justification for not pursuing drugs for rare diseases, but it also steers traditional companies away from potential profits, he argues—because biology, in truth, is too complex to be predicted. “That question is impossible to answer, because you just don’t know where the good commercial opportunities come from.”

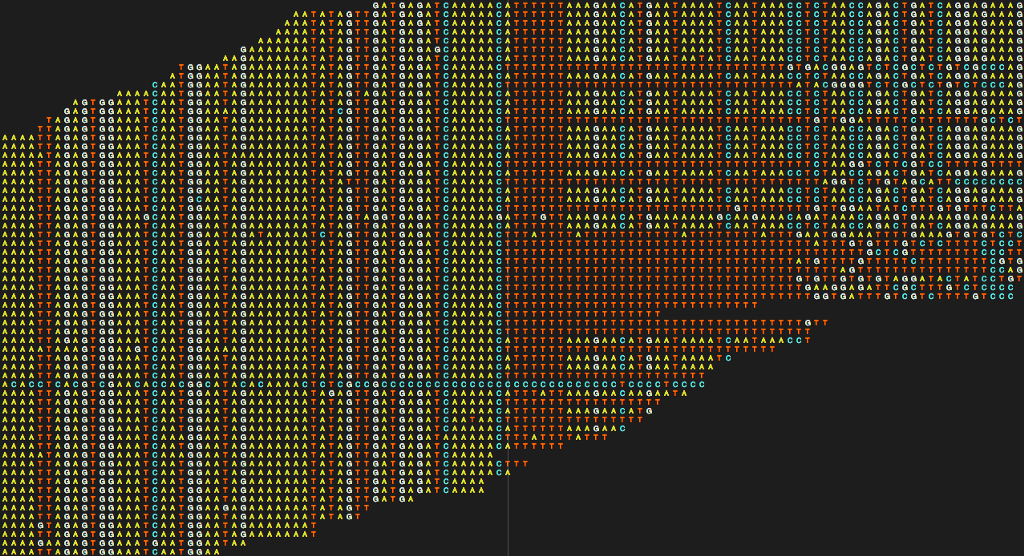

One potential therapy that Rarebase is developing is an antisense oligonucleotide, a synthetic strand of nucleotides customized to silence gene expression by glomming onto genetic transcripts and quelling the production of problematic proteins. Company scientists believe the particular nucleotide sequence they’re testing could have applications in many disorders. They are also developing Function, a data platform launching this month that’s designed to identify existing drugs for repurposing, some of them already FDA-approved for other conditions, and match them to rare diseases, based on gene expression.

That’s the project the Wolebens are participating in. Through the Cure Mito Foundation, one of two foundations Kasey cofounded to fund research, they paid Rarebase $50,000 to test RNA genetic sequences for Will, Doug, and another family member through the algorithm. The money is helping to develop Function into a more robust platform with the power to investigate more disorders. If it finds a potential match between these genetic sequences and an existing drug, the work will move to testing, which will cost more money. But if it’s an already-approved drug, the Wolebens won’t have to wait the years and raise the millions required for a clinical trial.

Kasey, after all her devastating disappointments, has chosen to trust Rarebase for a simple reason. “I have nothing else,” she says.

Onno envisions that this kind of rapid-cycle research on rare diseases could drive innovation in big pharma, the solution for one becoming a solution for many. “Whether you want to or not, I think a lot of innovation is going to happen in this space through these disorders,” where desperation tears down traditional hurdles, Onno says. “That’s why these rare diseases are a good starting point. [Rare disease families] have no other choice but to roll up their sleeves, because the big system doesn’t have the answer.”

Rarebase is officially a public benefit corporation, something halfway between a charity and a for-profit company, which allows it to act as a business but make decisions for the public good, not just shareholder or company profits. Since launching in July 2020, it has raised $2.6 million, largely from investment firm BlueYard but also from contracts with more than 25 patient foundations and families.

Kasey, after all her devastating disappointments, has chosen to trust Rarebase for a simple reason. “I have nothing else,” she says.

Shrinking tumors, growing hope

The odds of success in bringing any new drug to fruition are long, and Onno knows it. Biology is so complex, and our understanding of it still so incomplete, that searching for a breakthrough in any disease is like looking for a needle in a haystack—and you don’t even know if what you’re after will turn out to be a needle. In the three-plus decades that the National Organization for Rare Disorders has been giving research grants, only two resulting therapies have been approved by the FDA. Perlara, another public benefit corporation pursuing rare disease treatments (and another research venture that the Wolebens raised money for that produced no advances on Will’s condition), raised nearly $10 million in investments but fizzled out after five years for lack of funds.

But Onno believes the odds are better for rare disease than with more common diseases, because clinical trials are smaller, hurdles to FDA approval are lower, and big pharma has not already emptied its enormous pockets trying to find treatments. Besides, he doesn’t like broken systems. As a designer by nature, who invented and patented a better nail clipper as a child, he believes in the sensibility and possibility of solutions, and he’s restless unless he’s trying to find them. “It’s not the most tranquil life to do things like that, but I cannot help it,” he laughs. “If the path to a treatment of NF2 is like a windy road with pebbles and potholes and maybe a cliff, and this is the path for all these rare diseases, then I want to just build highways, make sure the road is more accessible.”

That’s why he’s chosen to strike a balance between going rogue and toeing regulations: testing ways to remake a system while playing squarely within it. But this venture, where the stakes are children’s lives, is his riskiest so far. With rare diseases, he says, “You can’t promise that you’re going to solve it. Research just doesn’t work that way. When I want to build an app I can pretty much guarantee that this app will be built, but with this you’re venturing into the unknown.”

Meanwhile, Onno is traversing unknown territory himself. The lapatinib felt so toxic, he says, “I even thought I’d probably rather be dead than live with this drug.” After it stopped working, he heard about another potential drug under study at the Neural Tumor Research Lab at UCLA. It was everolimus, an approved cancer drug that restrains cell growth but is not typically used for NF2. In order to try it, Onno had to benchmark how his tumor would grow if untreated—which meant deliberately letting it go unchecked for three months. At his next MRI, it had grown another 40 percent, to about 1.2 cubic centimeters. His insurance approved everolimus, and his tumor has actually shrunk back to 1 cubic centimeter since he started taking it in February 2020.

The side effects are much lighter than with lapatinib. But the drug suppresses the immune system, so Onno, who previously spent almost all his time working or socializing, has spent much of the COVID-19 pandemic alone in his apartment in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood. Reemerging with vaccines has made him realize how much he needs his connection to others—his friends, his collaborators, the fellow patients he has committed himself to helping—in sum, the many people he has brought together in pursuit of this goal.

For now, he can still hear them. But most tumors eventually develop resistance to any drug.

“Sometimes I feel like I’m on the tip of this wave where I’m living in a time and getting diagnosed at a moment where there is a chance that I can get away with this,” Onno says. Doing that means staying ahead of the wave, keeping the tumor under control for as long as he can, and buying enough time to connect the next dot.

“But I also feel like I might fall behind it,” he adds. “Either can happen.”

Editor’s note: Based on community feedback, we updated the language in paragraph 18 to more accurately reflect the medical status of the person it describes.