Waiting for the Unicorns of Sh*t

Microbiome research has huge implications for the very sick. But can startups get healthy people in on the action?

On the morning of my test, I cook up a bowl of oat bran (21 percent of my recommended daily fiber), top it with dried fruits and nuts, down it with a big cup of black tea, and set my gut timer ticking. Within a few minutes, my bowels call me to business.

That was on January 16, and I was a little more nervous about this process than usual. I had just received a kit from the startup company Viome, whose goal is to “digitize, decode, and decipher human biology to prevent, treat, and cure chronic diseases and cancer,” according to their website.

I unwrapped the collection box they sent me and read the directions before eating my gastrocolic-stimulating breakfast. The kit contained a strip of reinforced paper with little sticker sides that attach to your toilet seat. There’s a fold across the middle of the paper creating a downward-facing triangle right above your toilet water, without touching. That’s your bullseye. I stuck the paper down on my toilet seat and then unstuck it and moved it a few inches forward, worried about my aim.

There was no need to stress, because I hit the middle of the paper triangle like I was born to it. I pulled out the other part of the kit, a test tube filled with a clear liquid. When I unscrewed the lid, there was a small scoop attached to the end of it, like a half-teaspoon measuring spoon. The instructions specified that I needed to dig out a sample “the size of a green pea, NOT heaping.” I did so and then shook my unique blend of digested food, bacteria, viruses, and fungi in the solution as directed (three times, for thirty seconds, with thirty second gaps in between). It was unassuming in a tiny plastic tube, but it was a sample of a whole community—my community—trillions of extra-small companions, which live inside my gut and qualify me (and you) as a superorganism.

And as I shook, I thought of all my little buddies about to take a trip via prepaid post.

The rise of the gut microbiome

Modern medicine’s fervent focus on all things fecal is fairly new. In 2007, researchers from The Institute of Genomic Research analyzed about 78 billion base pairs of microbe DNA and concluded “humans are superorganisms whose metabolism represents an amalgamation of microbial and human attributes.” The same year, the National Institutes of Health launched the Human Microbiome Project, which sought to learn exactly which microbes live inside us. And they began to correlate imbalances in these internal ecosystems with a host of illnesses, like inflammatory bowel diseases and colon cancer. More recent research has connected the gut microbiome to everything from preterm birth, to midlife cognition and aging, to freakishly specific roles, like controlling seasonal fat storage in pandas.

If the bacteria from probiotics integrated themselves into your gut community, you wouldn’t have to keep taking the probiotics.

Probiotics, whether carried in foods like yogurt and kombucha or taken as supplements, are bacteria and fungi sold on the premise that they will lodge in your gut and generally improve the neighborhood. But the science around whether they will actually change your microbiome is controversial. Our environment and our diet shape our microbiome much more than probiotics can. “Most pass right through the gut,” says Eugene Chang, medical professor and director of the Microbiome Medicine Program at the University of Chicago. They never settle in for the long haul, he adds, comparing microbial communities to human communities.

“They don’t want insiders coming in,” Chang says, “and they build defense mechanisms.” If the bacteria from probiotics integrated themselves into your gut community, he says, you wouldn’t have to keep taking the probiotics.

Early on, microbiome research made a big splash when doctors showed altering the composition inside the gut could have practical implications for the very sick, especially for people in one particular situation: a C. diff infection. The bacterium Clostridioides difficile is one of the most noxious weeds of gut microbiota. When everything else in your intestines is wiped out by antibiotics, C. diff persists. It can take over your insides with a vengeance, causing potentially deadly diarrhea and colon inflammation.

Doctors have been performing fecal transplants for C. diff patients since 1958, according to an interview in the journal Gastroenterology & Hepatology with Lawrence J. Brandt, medical professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. He says he performed his first transplant in 1999. In 2012, he began to get five to eight calls or emails a week requesting the procedure. Fecal transplants are now used in the United States and Europe to treat C. diff, although regulation is still in the process of catching up to the research.

Majdi Osman is an infectious disease doctor who became interested in nutrition, especially nutrition for kids who have suffered from severe malnutrition. Nonintuitively, even after these children were nourished with therapeutic foods, they kept having poor growth and diarrhea—with potentially deadly consequences. That’s what Osman was trying to investigate when, one Friday afternoon during his clinical training, he assisted in a fecal transplant. At that time, there weren’t easily accessible, pre-screened fecal samples, so the doctors asked one of the patient’s relatives for some. “So it’s very busy and sort of chaotic, but we were able to get the treatment done,” says Osman. “And the patient, when I saw her on Monday, after the weekend, she was sat up in her bed, eating, doing well, ready to go home.” He soon met the founders of the OpenBiome project, a nonprofit dedicated to creating and storing “fecal microbiota transplants” to share with doctors and researchers—and is now the chief medical officer there.

Researchers like Osman and the people he supplies with pre-screened fecal samples have been investigating the potential for probiotics and fecal transplants for about a decade now, but not really for people like me. The scientific community is filled with research looking to see if probiotics help with severe eczema, colic, liver disease, ulcerative colitis, gout, or other serious medical conditions, but not studies considering their effect on otherwise healthy people who want more energy or less gas, which is promised in glowing reviews of some of the at-home stool analysis and probiotic testing kits. Even with the serious health problems, study results vary, and in nearly every scientific paper I read, the authors write that more research is needed.

Golden stool

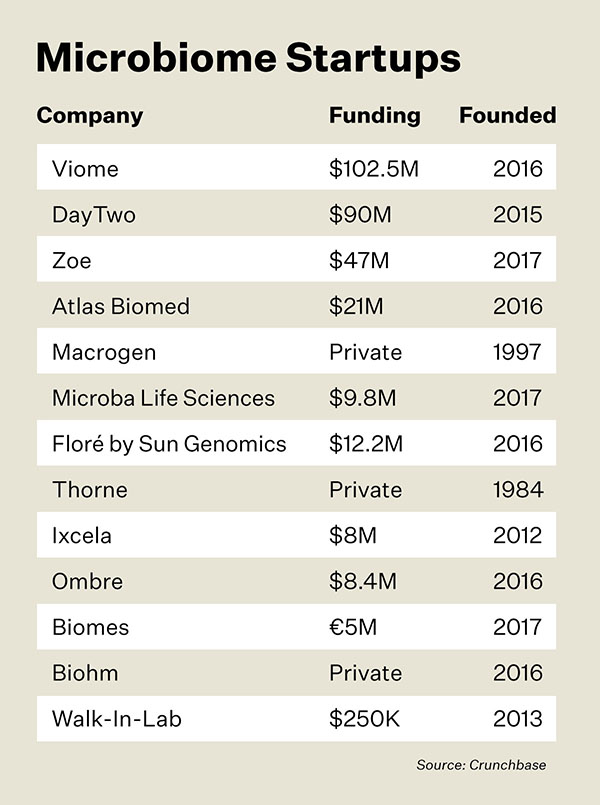

Obviously someone believes in what the exploding field of microbiome startups are selling—or at least a few people with a whole lot of money. Viome has raised $102.5 million from investors like Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce. And in order to begin digitizing, decoding, and deciphering human biology, they need well-timed and well-placed samples from lots of willing humans.

But people are interested in the implications of the gut microbiome to their health now. And there’s a lot of money at stake. Startups like Viome, DayTwo, Zoe, Atlas Biomed, Macrogen, Microba, Biohm Health, Biomes, Ombre, Ixcela, Thorne, Floré, and Walk-In-Lab raised more than $1 billion between 2016 and 2020, according to Crunchbase. The thought process of investors makes sense: They’re presumably dreaming of cutting into the global vitamin and supplement business (worth $119.66 billion in 2020, according to Fortune Business Insights) and the holy grail: the U.S. diet industry (which accounted for $214.7 billion in 2016, according to Grand View Research).

Microbiome startups have taken at least a few iterations to get it right. There has already been a Theranos-like disaster in the world of commercialized bacteria, fungi, and virus testing. On April 26, 2019, Sally Shin, then CNBC San Francisco bureau chief, posted a dramatic video on Twitter of FBI special agents raiding the office of uBiome, a microbiome sequencing company. The SEC charged Jessica Richman and Zachary Apte, the company’s cofounders, with fraud in a 33-page indictment. They’re accused of scamming investors out of $60 million by portraying uBiome as a success instead of what it actually was—not quite there yet. If convicted, the married founders could face up to 22 years in prison, although they are reportedly now fugitives in Berlin.

Another company called Arivale, which counted as one of its cofounders legendary genomics pioneer Leroy Hood, set itself up in this space to measure blood, lifestyle, and microbiome data, but it also folded—albeit with no courtroom drama or flights to foreign countries. Nevertheless the unremarkable end to that company might still give investors some pause about the field. According to the goodbye note on their website, “the cost of providing the service exceeds what our customers can pay for it.”

I reached out to every still-existing microbiome startup I could find. They vary immensely in how legitimate they appear—and for that matter in how responsive they were. Some, like Viome and Atlas Biomed, have snazzy websites and attentive PR people who sent me gut testing kits and arranged interviews. Others seemed like thinly veiled attempts to gather my health data for advertising. Biohm Health gave me an online quiz that determined my microbiome health was five to eight out of 10 (the error bars on that one!). On the basis of my self reporting, they ruled out the likelihood I had candida infection, a common fungal overgrowth caused by yeast, but they pointed me to three $45 probiotic powders I could try anyway. Biohm has sent me 15 emails advertising their probiotics since I took the quiz 16 days ago, though I should note Biohm says they “do not share individual-level genetic data or survey responses with third parties.”

Several of the companies mentioned above don’t come off as if they’re full of sh*t. They’re more ambitious about what their products can do for human health. Firstly, they advocate for diet changes before they talk about probiotic supplements, if they mention probiotics at all. The history of diet change is long, fraught, and controversial, but food does seem like a much more effective way to change the microbiome than probiotics. I can’t peer into any of these company’s proprietary algorithms to affirm that they were right to recommend you avoid apples, but I can offer you this: Different foods seem to affect people’s microbiomes differently. Study after study has found changes in the way different people’s blood sugar responds to various foods based on their microbiomes. Chang discussed a patient with irritable bowel syndrome he has been working with whose microbiome can’t deal with many different foods, but it can deal effectively with lactose. “That was like, ‘Oh, my God, I never thought I could take milk or cheese,’” says Chang. “Just that alone, his quality of his life went up.”

If you do a gut microbiome kit, you usually meet with a nutritionist to discuss your results, and you can do another test to see if your bespoke program is working (for a few hundred dollars more, of course). These companies all say they care about data security, and some promise encryption, access to data only for people who need it (like your designated nutritionist), the ability to destroy the sample upon customer request, and of course never selling your data to third parties. Many are sticking their toes into the world of human genome testing as well, to get the full picture of their customers.

Of course, these businesses cater to those who can afford the $200 tests. In the life-savings-shattering American health care system, that’s not a lot of money. But only 61 percent of people in the United States could handle a $400 cash emergency in 2018. And about 13.5 million Americans live in food deserts, lacking access to what the U.S. Department of Agriculture defines as “healthful foods.” Since the uBiome catastrophe, these microbiome startups are understandably cautious about seeking the status of a medical test, so they currently operate firmly outside the health care system.

The bottom line

I received my Viome results shortly before going to press. According to the app, I am supposed to eat bespoke “superfoods” like alfalfa sprouts, anchovies, and fresh artichokes, while avoiding the “wrong foods,” like arugula and watercress. The Viome app also has a “foods everyone should avoid” section that includes what you would expect, like sugar, white flour, and salt.

The most interesting part of the results was when I scrolled down my “wrong foods” list and noticed my personal archnemesis: the bell pepper. I like eating all vegetables except bell peppers, which I loathe and find myself constantly encountering, since they have a tendency to work themselves into many different plates. I hate the way they smell, the way they taste, and the lingering olfactory nightmare caused by my roommate when she left several to rot in our tiny college dorm room fridge.

When I clicked on the icon to learn more, the Viome app told me that “Your microbiome contains pepper mild mottle virus, which is known to infect bell pepper. Since plant viruses in the microbiome have been associated with Immune System Activation, it is recommended for you to avoid bell pepper.” A lifelong mystery, ostensibly solved! Underneath the caption, the app directed me to two research papers on the “human gut virome.”

Only 4% of the Viome population scored in the “good” range.

Immediately after this thrilling discovery, however, caution came to me in the form of my boyfriend warning me about my own confirmation bias. I picked peppers from a list of wrong foods. The test also instructed me to avoid paprika because my microbiome contains paprika mild mottle virus, and I like paprika.

Viome also offers a “precision supplements complete” subscription service providing a 30-day supply of my personalized supplements, along with an assortment of probiotic and prebiotic powders, for $150 a month. My total gut microbiome health score was “average,” along with 65 percent of other Viome users. Only four percent of the Viome population scored in the “good” range.

If I were motivated by a gastrointestinal problem, I might take several months or years to experiment. If I followed the Viome diet and took the expensive supplements, would I eventually score among the elite four percent of people with “good” gut biomes? More importantly, would I feel better? Ultimately, the science is still out. You won’t find these kits at the doctor’s office yet, and there’s no indication of when they will become a routine, respected, and reimbursed part of primary care—or if they ever will. I reached out to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and they do “not have a stance on microbiome testing.”

For the highly motivated, however, the kits are sold online and available widely as mine was, to drape, scoop, slosh, seal, send, and await the results. But perhaps that’s the rub. Was I, a strong-stomached journalist researching an article, a good candidate for a microbiome kit in the first place?

Personally, I wouldn’t order the kit again. But if you’re curious and have a few extra dollars to spend, feel free to follow your gut.

Editor’s note: This story was updated on 3/3/22 to reflect Thryve’s rebrand to Ombre.