As organ-on-a-chip technology comes of age, the bipartisan FDA Modernization Act 2.0 would remove the requirement that new drugs must undergo animal testing before human clinical trials.

The list of people and organizations celebrating a potential new law modifying a longstanding FDA mandate on animal testing is long, broad, and bizarrely eclectic. It may be unprecedented for a proposal in Congress to make bedfellows of Rand Paul and Bernie Sanders, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and the Cato Institute, and famed primatologist-turned-conservationist Jane Goodall and Texas congressman Marc Veasey, the former vice-chair of the pro-hunting Congressional Sportsmen’s Caucus.

The proposed new law, known as the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, does just that.

This obscure legislative change basically swaps a few words in the existing section of U.S. Code that governs the development of new drugs in the United States. In one place it changes the word “preclinical” to “nonclinical,” and in another it replaces the word “animal” with the more anodyne “nonclinical tests or studies.”

That may not sound like a lot. But experts say the implications of the new bill are profound. Enshrined into law, it would eliminate an 85-year-old requirement that pharmaceutical companies must test drugs on animals before starting clinical trials in people and would usher in a new era of cell-based or computer-based testing instead.

Passed unanimously in September by the U.S. Senate, the bill faces a promising outlook in the House. Its fans include both Democrats and Republicans, high-profile individuals, and groups including the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation, the National LGBT Cancer Network, the National Hispanic Medical Association, and at least 117 organizations devoted to animal rights. The Senate bill was sponsored by Rand Paul (R-KY) and Cory Booker (D-NJ), whose views on most issues do not converge. In a sign of how popular the legislation is, Paul hosted a “puppy press conference” to promote it last October, featuring staffers and their dogs out on the lawn.

“Everyone knows the animal models are terrible.”

This rare consensus across bipartisan lines represents a scientific tipping point into an era where new technologies can now outperform animal studies for many indications, says cell biologist Don Ingber, the founding director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University in Boston. Animal research continues to benefit people in a variety of ways and is unlikely to disappear altogether, he says. But given a strong preference for alternatives on both sides of the aisle, the change could potentially be a win for animals, people, and science.

“Everyone knows the animal models are terrible,” says Ingber, who has founded several companies including Emulate, which creates versions of a technology known as organ chips for research studies. “The drug companies know it. FDA knows it. It’s been known for years. Nobody has ever questioned that. But there has been no alternative.”

Now as other options are showing greater proof of principle, he says, there is enough momentum to make regulatory changes.

A coin flip

The U.S. government has been requiring companies to perform animal studies with new drugs and cosmetic products since 1938 as part of the FDA’s Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The act was developed in response to a series of disastrous events, according to a historical publication by the National Academy of Sciences. In 1933, for instance, a cosmetics company in California began to sell a permanent mascara product called Lash Lure. The makeup contained the chemical p-phenylenediamine, which caused horrible blisters on faces and eyes, blinding more than a dozen women and killing one. A few years later, a drug company in Tennessee reformulated an antibacterial sulfa drug by adding ethylene glycol to make it sweeter and more appealing to children. Ethylene glycol, which is the primary ingredient in antifreeze, is poisonous. The product, called Elixir Sulfanilamide, killed 107 people, most of them children.

Before early efforts to regulate medications, the landscape of drugs that could be marketed as medicine to consumers was essentially a free-for-all for snake-oil salesmen, says Gail Van Norman, a physician and clinical ethicist at the University of Washington, Seattle. Because people were potentially being harmed, the FDA’s initial regulatory priority was safety. It took a few more decades until 1962 for the agency to add an amendment requiring companies to show not just that drugs were safe but also that they worked in animals before moving on to trials involving people.

And while scientists have used animals to develop many drugs since then, evidence has been accumulating for years showing that animal studies often only weakly predict the safety or efficacy of drugs in people, Van Norman reported in a 2019 analysis. One 2007 review of 221 animal experiments found that results in animals predicted results in people just 50 percent of the time. A 2015 study on the toxicity of 37 chemicals in rats and people showed the same kind of coin-flip results.

As many as 90 percent of new drugs fail in human clinical trials, according to some estimates, and animal studies don’t seem to be helping enough to improve a drug’s chances of being tolerated or effective in people. When scientists looked at 93 serious adverse reactions to approved drugs, they found that animal studies predicted only 19 percent of them. Even when drugs make it to store shelves, a quarter of them get removed within four years, she says, often because of safety reasons. “We’re really approaching 50 percent of the drugs that are safe in animals not being able to continue in the market because they are toxic to humans,” Van Norman says. “Fifty percent is random chance.”

Good models gone bad

Animal experiments have been a mainstay of science since the time of Aristotle, and there are plenty of good reasons why, Ingber wrote in a 2020 paper. Mice, rats, dogs, and monkeys have traditionally been the most frequently used animals because of similarities in certain systems and for other reasons. Since the advent of genetic engineering, scientists have been able to engineer animals to serve as models for diseases with specific features, like the abnormal accumulation of proteins, called tangles, seen in people with Alzheimer’s. Gnotobiotic mice are engineered so that every microbe in their system is known, which can be useful for researching links between the microbiome and health.

Still there are multiple reasons why animal models might not adequately predict human responses, says Ingber. An animal might show all the same symptoms of a human disease, like sepsis, but its body can use different pathways to become sick. New classes of drugs and advances in precision medicine add to the discrepancies. Nearly half of new drugs are biologicals, which include monoclonal antibodies, adeno-associated viral gene vectors, and CRISPR RNA therapeutics. These medications can be so specific to human biology that they don’t even react with molecules in non-human primates, Ingber says.

To meet current FDA rules, Ingber says, drug companies sometimes have to make different versions of drugs to test in primates before they can launch trials with people—an endeavor that can be expensive, ethically questionable, and scientifically absurd.

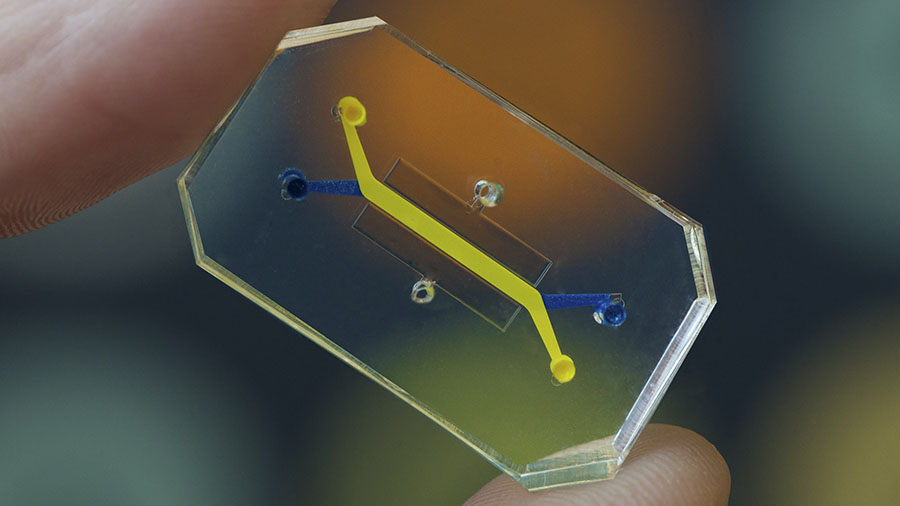

Over the last decade, scientific developments have started to offer new and better ways of mimicking human biology, Ingber says. With a breakthrough paper in Science in 2010, he pioneered the development of organs on chips, one of the key technologies that could replace animal studies for understanding the function of drugs in the human body. The specific organs on chips he has produced are clear silicone rubber devices, about the size of pink school erasers, that contain tiny hollow channels and a membrane lined with human cells, and they are designed to mimic the structure and physiology of human body parts.

That’s the advantage of organ chips over just studying human cells: They can mimic real processes—breathing in the lungs, peristaltic movements in the intestines, and uniquely human microbiome communities. The chips can analyze the way drugs change in concentration over time in the human body depending on dosing regimens. Their humanlike qualities can produce more relevant results, and the fact that they are mounted on a transparent chip makes them easier to observe, Ingber says. “You get insight into the mechanism of drug action, the mechanism of drug toxicity, the mechanism of disease,” he says. “Animals are kind of a black box.”

In 2001, 65% of people said that animal research was morally acceptable. By 2017, approval rates were down to 51%.

In March 2021 Ingber was invited to speak to Congress alongside conservationist Goodall at a House subcommittee hearing on the new FDA regulation. He offered numerous examples of what organs on chips can do that animal models can’t. In his lab, his group has developed at least 15 organs on chips, including intestines, lungs, kidneys, and lymph nodes. They have linked organ chips together to make humanlike body systems. And they have used those devices to study rare genetic diseases and radiation exposure, and to measure the human response to drugs that might fight influenza and coronavirus.

Toxicity testing is where organ-on-a-chip approaches may really shine. Using liver chips to test more than two dozen drugs, Ingber and colleagues were able to predict toxicity seven to eight times better than animal studies could, the team reports in a study that is soon to be published in a scientific journal and was posted online as a preprint in August. Often companies will go back to data from failed trials and crunch numbers to see if there’s some sub-population of patients who benefited and should be the subject of a more targeted trial, Ingber says. Organ chips could save years of time and millions of dollars by testing drugs on people from the same genetic sub-population or with other common characteristics.

These chips aren’t the only technologies that are diminishing the need for animal models. Other labs have engineered tissues and grown organoids from an individual’s cells, allowing them to test personalized cellular responses to medications. Computer models have also advanced enough to allow scientists to screen the potential uses and risks of many chemicals at once, Van Norman says, helping to refine the search for new drugs and find new uses for existing drugs. If enacted, the new law could be a win for companies taking AI or computer-based approaches alone or in combination with organ chips to test for drug toxicity.

Shake paws with Sparky

However much things change within the pharmaceutical industry, the advance of the bill to the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives is a huge win for animal rights groups, many of which have been campaigning for years to sway public opinion against the use of animals in laboratory experiments.

Those efforts finally appear to be paying off. In 2001, 65 percent of people said that animal research was morally acceptable in a Gallup poll. By 2017, approval rates were down to 51 percent. Opposition to animal research grew from 25 to 44 percent in the same time frame. That societal shift, Van Norman says, probably helps explain the wide support for new regulations in Congress, which tends to bend where the wind blows.

Besides that, animals are a cute and easy photo op for politicians. “I was unaware until the last couple of months that it was required to do animal testing before you got to human testing,” Paul said, announcing his co-sponsorship of the bill in his puppy press conference last year, which took place on a grassy lawn with barking dogs, wagging tails, and drooling onlookers.

“I think sensibilities change over time,” Paul said.

The ultimate fate of the bill still depends on getting approval of the House and then being signed into law by the president. The House has not announced a timeline for a vote or whether that will happen before next month’s midterms. But it appears to be popular in the House as well. A related bill was introduced there in April 2021, and it currently has 98 cosponsors. If or when it passes, its impact will be significant, politicians say.

“The FDA Modernization Act 2.0 will accelerate innovation and get safer, more effective drugs to market more quickly by cutting red tape that is not supported by current science, and I’m proud to have led the charge,” Senator Paul wrote in response to a request for comment from proto.life. “The passage of this bipartisan bill is a step toward ending the needless suffering and death of animal test subjects—which I’m glad both Republicans and Democrats can agree needs to end.”

If anyone stands to lose from the new rules, it’s the industry that produces millions of animals for research each year.

Booker didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment, but he issued a statement after the unanimous Senate vote. “The passage of my bill will avoid the needless suffering of countless animals, now that experimental drug testing can be done with modern non-animal alternatives that are more scientifically relevant,” Booker’s statement reads. “This legislation brings us one step closer to eliminating the cruel practice of unnecessary animal testing.”

Nevertheless, animals are unlikely to disappear from science altogether, Ingber says. The use of genetically engineered mouse models remains entrenched in science. And, he says, they are still the best tool for studying certain conditions and processes, like the effects of gravity on bones or complex, systemic hormonal interactions or behavioral changes. If anyone stands to lose from the new rules, Van Norman adds, it’s the industry that produces millions of animals for research each year.

As for the much larger pharmaceutical industry, it is mostly mum on the new proposed law. proto.life could only identify one drug company, Tel Aviv-based Teva Pharmaceuticals, that has outwardly supported the bill. Pfizer has said on its website that it is committed to reasonably reducing or replacing animals in its drug research—or at least minimizing their pain. proto.life has reached out to numerous industry experts to find one willing to comment specifically about how the new law will impact Big Pharma. At the time of publication, only Novartis responded through a spokesperson who said the company has no comment on the bill, but she shared a link to their website that emphasized the importance of animal research and the company’s commitment to animal welfare.

Still, the fact that there has been no obvious vocal opposition to the new FDA rule inside Congress is its own kind of marvel, Ingber says. “I think it’s great that there is finally something going through Congress that both sides support,” he says. “It is almost miraculous.”