Sarcopenia, a muscle wasting disease, could shorten your life and is alarmingly prevalent. Why are so many people unaware it exists?

Even if you don’t know his name, you’ve probably seen a photo of Mike Schultz. The 45-year-old nurse and bodybuilder lost 50 pounds during a 57-day hospital stay after he was diagnosed with COVID-19 at the height of the pandemic. His before-and-after shirtless selfies went viral, a warning for others to avoid infection. Schultz had no pre-existing conditions but still experienced extreme muscle wasting.

Muscle wasting is a widespread symptom of a disease that most people have never heard of: sarcopenia. “Probably 20 percent of people over the age of 65 or 70 should be diagnosed with sarcopenia,” says Bill Evans, the University of California, Berkeley, physiologist who first described sarcopenia.

Like memory loss, sarcopenia was traditionally seen as a normal part of aging, but is now recognized as a disease. It still lags far behind dementia in terms of research funding and everyday familiarity, partially because it’s ill-defined and poorly understood.

“Sarcopenia is not just muscle mass changes that come with the age,” says Micah Drummond, a muscle biologist at the University of Utah. “It’s a loss of muscle mass, loss of strength, and loss of physical function. And they come with various severities.”

Because sarcopenia is misunderstood and poorly defined, it’s harder to design trials to diagnose and treat it.

Not everyone agrees; some experts even call normal muscle loss with age sarcopenia.

Clinical trial funding requires the trial to address an established problem using a cleanly defined metric. Because sarcopenia is misunderstood and poorly defined, it’s harder to design trials to diagnose and treat it. What counts as treatment success for a disease with few quantitative symptoms? Without those parameters, it is harder still to win funding for such studies. But change is on the way.

“There’s been quite a bit of dialogue in the last few years between pharmaceutical companies, academics, and the regulators. I think we’re beginning to make progress there,” says Miles Witham, a sarcopenia and aging expert at England’s Newcastle University.

Muscle loss: normal aging or disease?

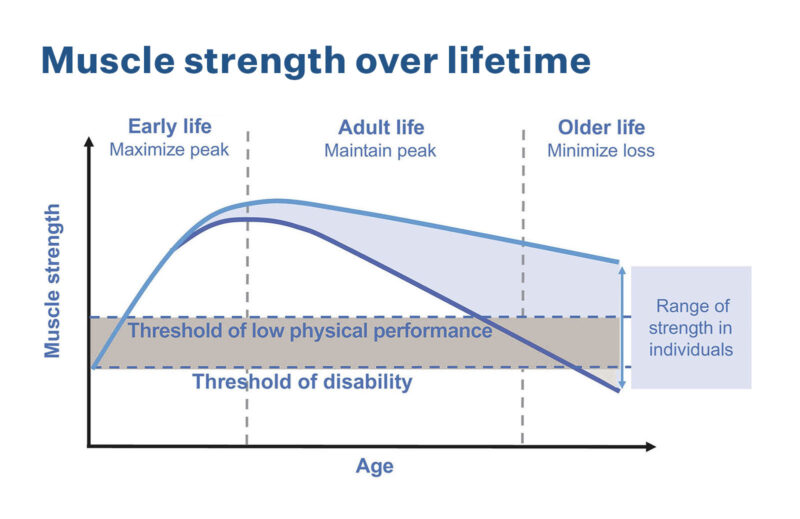

Everyone loses muscle mass as they age, and in older people the cumulative loss of strength and function is a fundamental cause of disability. “If we can prevent that, if we can treat that, then I think that the promise is that most of us can remain independent until we die. That’s the goal,” Evans says. “One of the things that has to happen is that the public has to be aware that this is a preventable problem and a treatable problem.”

In the clinic, diet and exercise modifications are the gold standard for treating sarcopenia. Clinicians hope older people can build or rebuild enough muscle by eating more protein and exercising. Unfortunately, the best treatment for the disease is prevention; protein supplementation is of little use to people who cannot convert it to muscle with exercise. Often, by the time sarcopenia is diagnosed—if it ever is—a person’s abilities are so limited, and their complications so numerous, that it’s difficult to treat.

“As you’re getting older and older, [gaining] muscle back is very difficult, almost impossible,” says Hans Dreyer, a University of Oregon muscle physiologist.

Currently, there are no cutting-edge therapeutics available for people with sarcopenia. Hormone therapies and drugs like metformin and myostatin inhibitors, which are designed to increase muscle mass, are being tested without standout success so far as scientists strive for a trifecta of improved muscle mass, strength, and function. Alongside pharmaceutical tests, physiologists are devising new ways to measure muscle mass that are accurate, non-invasive, and cost-effective. But with limited funding for an ill-defined disease, progress has been slow.

Another challenge is that many sarcopenic people have a host of other ailments that can confound simple tests for muscle loss. For example, loss of coordination can be a sign of neurological issues or cognitive decline, with or without changes in muscle function. So it is challenging for geriatricians to diagnose sarcopenia distinctly from other existing conditions. And muscle loss itself often leads to frailty and loss of independence in older people, creating a frustrating cycle of limited mobility that leads to falls, injuries, and further functional decline. Sarcopenia is linked to heart disease, respiratory disease, cognitive disorders, and shortened lifespans.

Even if physicians and researchers can’t quite agree on how to define sarcopenia, it is killing people. Older adults with decreased walking speed, a common outcome of sarcopenia, have a 76 percent higher risk of dying than their peers.

Diagnosing muscle loss

Sarcopenia wasn’t recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) until 2000, and it didn’t receive an ICD-10 code until 2016. ICD (International Classification of Diseases) codes are a WHO classification system for diseases and symptoms. In the United States, these are often used by insurance companies to determine which therapies are covered under a given health plan. Without a code, it can be harder to qualify for treatment.

Experts don’t agree on the best definition or diagnostic methods for sarcopenia—or even on the fundamental question of how much loss is “acceptable.” Is sarcopenia age-related muscle loss? If so, how much muscle loss qualifies as normal aging versus a disease? There is no way, at present, to differentiate between so-called normal muscle loss associated with aging and excessive muscle loss.

“My goal is to get muscle mass as the diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia.”

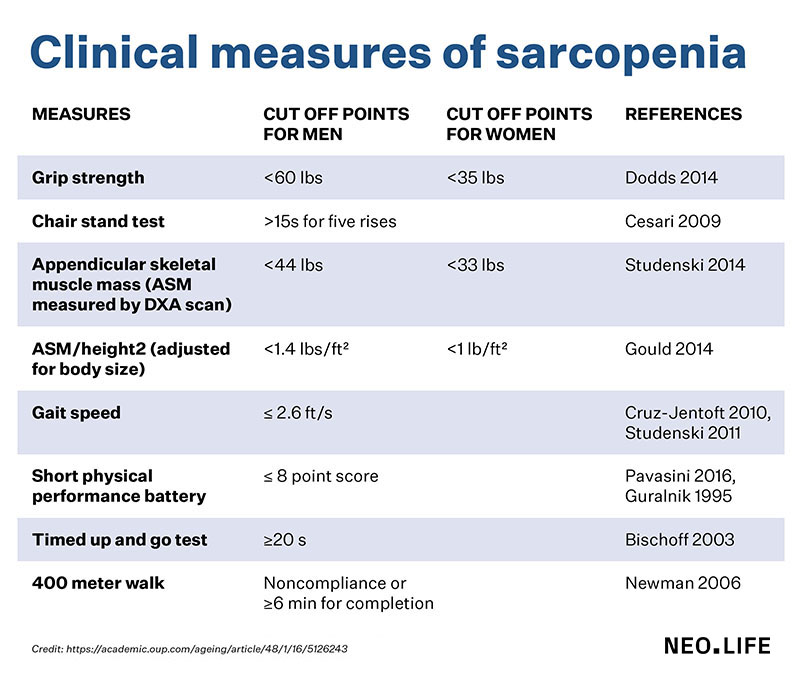

Physicians who diagnose sarcopenia use a range of tests, including a five-question survey, but the questionnaire can’t be used in people with cognitive dysfunction. So doctors also rely on proxy tests, such as grip strength or a simple chair test, in which the provider counts how many times a patient can stand up from a seated position without assistance. Doctors also use measures of walking speed as an indirect indicator of sarcopenia. Some experts say testing for sarcopenia should include more directly measuring the loss of muscle strength and function, as well as muscle mass. But even those measurements can be controversial. For example, muscle strength can be measured with a static hold or a dynamic movement.

“My goal is to get muscle mass as the diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia,” Evans says. “Not everybody who has poor function has low muscle mass, but everybody that has low muscle mass has poor function.”

The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) updated their criteria for sarcopenia in 2018. They suggested diagnostic parameters for various tests, and they defined the disease as a combination of low muscle strength and low muscle quality/quantity. Severe sarcopenia is described as these symptoms paired with poor physical performance, such as difficulty walking or standing up. In younger people like Schultz, acute sarcopenia can occur alongside a serious illness or injury. Despite these strides, EWGSOP acknowledges that their guidelines have been used much more widely in research than in clinical practice. Evans says many physicians, even geriatricians, are unaware of sarcopenia.

Witham suspects that different causes (infection, cancer, aging, etc.) of sarcopenia will ultimately demand different types of treatment.

“It’s important to frame it as a condition rather than an inevitable part of aging,” he says. Still, “whether it’s due to you having some other underlying issues or whether it’s just that you’re not moving much around, if you’ve got sarcopenia you’re at increased risk of death, of needing care, and of falling over and getting into hospital.”

Whatever its cause, sarcopenia shortens lifespans.

Part of the problem has been a lack of accurate, affordable diagnostic tools for measuring muscle mass. Scales sold to consumers to measure body composition are often inaccurate, as are even more complex tools. Because muscle fibers are interwoven with fat, similar to the effect of marbling on a piece of meat, it’s difficult to determine how much of what appears to be muscle tissue actually is. Doctors can use CT scans and MRIs to measure muscle, but such scans are expensive and hard to justify without clear parameters for what constitutes low muscle quality. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scans are a more economical tool, but the machines aren’t portable, tend to produce inconsistent results, and can be skewed by dehydration.

A pill to prevent muscle wasting

So what does the future hold? The experts say there are two areas of research now unfolding at once. One arm of science is trying to find precise biomarkers for muscle wasting. Another is working to develop new exercise protocols, nutritional practices, and pharmaceutical treatments to mitigate the impacts of the disease.

Until recently, lean mass measurements, which include muscle, bone, organs, and bodily fluids, were used as a surrogate measurement of overall muscle mass. But this method, which proved inaccurate, skewed study results, making it appear that muscle mass was not related to increases in mortality.

“It led to what I think is the mistaken conclusion that muscle mass was not important,” Evans says. However, “strength has shown to be important for these outcomes. And my position has been that strength is really just a surrogate for how much muscle you have.”

Researchers have now demonstrated that loss of muscle mass is associated with disability, hip fracture, and mortality. The loss of lean mass is not, Evans says. He’s currently working on a D3-creatine dilution diagnostic, which measures a waste product of creatine, creatinine, in urine output. Because the majority of creatine in the body is in muscles, measuring how much creatinine (a byproduct of creatine metabolism) is excreted in urine can serve as a proxy for muscle mass. Evans is currently seeking FDA approval for the test, and he has used it on 2,000 research subjects so far, hoping to establish a threshold for normal muscle loss with age.

Trials for hormones like testosterone and selective anabolic receptor modulators (SARMs), which are safe for women, have shown promise, but for people in poor health, the side effects may outweigh the benefits. Testosterone, for example, could accelerate the growth of prostate tumors. SARMs, which are similar to anabolic steroids, are safe for all genders, but still have side effects. “Their safety profile is not great,” says David Church, a University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences muscle biologist. Plus, muscle growth doesn’t equate to muscle strength.

“It’s nice to have the muscles but if they’re not functional, then it’s really kind of a moot point,” Drummond says. Myostatin inhibitors have had the same problem: They tend to result in muscle growth without functional improvements.

Other drugs have shown promise in animal studies that didn’t translate to human findings. The diabetes drug metformin has been seen as a potential anti-aging drug, but it also limits muscle growth with exercise, a clear drawback for sarcopenic patients.

“If you could give your mom a pill that would keep her out of a nursing home, you would pay for it yourself.”

Fickle funders haven’t helped. Dreyer found that essential amino acid supplements helped to reduce muscle loss after knee replacement procedures in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, but was unable to secure funding to continue the project. Researchers who have studied the impacts of heat therapy in reducing muscle loss have similar complaints about funding.

Further back in the pipeline, Church is running a clinical trial for an oral amino acid tolerance test that measures muscle function through a series of blood tests after participants consume a 10-gram dose of crystalline amino acids. Measuring the time from when the amino acid leucine peaks in the bloodstream until it’s cleared can be a proxy measurement of muscle function. Ultimately, Church hopes that, like an oral glucose tolerance test used in pregnancy, this test could be an inexpensive, practical diagnostic for clinics without expensive equipment.

Another very early-stage project comes from the startup Immunis, which is recruiting patients for the first phase of a clinical trial for its secretome therapy, which is based on isolated cell secretions—in this case, proteins that have a role in renewing muscle cells. The secretome therapy is injected locally and will be tested first in people with knee osteoarthritis, which can lead to muscle loss. Drummond sits on the Immunis advisory board.

As research continues, scientists must weigh each pharmaceutical’s side effects against its potential benefits. People with sarcopenia are a difficult group to treat because of their frailty, which makes them less resilient to side effects. Still, researchers are optimistic that with growing interest in sarcopenia, and ever-better diagnostic tools and criteria, the FDA will approve a pill for muscle wasting in the next few decades—small comfort for older adults today. With people living longer than ever before, a therapeutic that helps them remain independent longer could change the face of aging.

“If you could give your mom a pill that would keep her out of a nursing home, you would pay for it yourself,” Evans says.