With 27 biological children and three surrogate pregnancies under her belt, it’s all business as usual for Tyra Reeder.

When Tyra Reeder was six months pregnant, she was bored one night and began swiping through photos on Bumble, the dating app where only women can make the first move. It had been a year since her last relationship ended, and she was ready to meet someone new. That evening a photo of a man with big warm hazel eyes caught her attention, and she sent him a flirtatious message.

“So you’re a surrogate?” the man, named Tory, wrote back.

“I sure am,” Tyra said. She had listed surrogacy as her job description in her profile. She also had written, “Cigarettes and kids will kill you.”

“How do you like it?” he asked. “Hope that wasn’t too personal, just interested.”

“I love it,” she wrote back. “Feel free to ask any questions.”

“What made u decide to do that?”

“It’s my second time,” she replied. “I didn’t mind being pregnant the first time, and it’s great money. Makes me feel like I have a great purpose and am helping someone. That sounds cheesy LOL.”

I met Tyra Reeder a few years ago when I started reporting a book I’m currently working on about how new choices and reproductive technologies are changing family life, and I’ve continued to follow the course of her life. In a recent interview, she shared this initial text exchange with Tory.

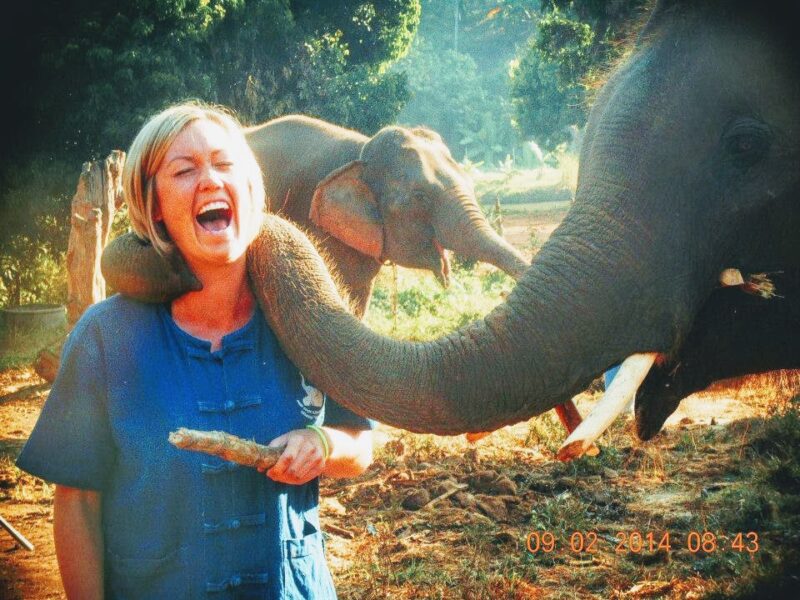

Tyra, who is 37 and originally from rural Idaho, is clear with any potential dates that making babies is just a business transaction for her—albeit an all-encompassing one. During her online chats with Tory, she told him that she had a son when she was 17, and she gave him up in a legal open adoption to close family friends who couldn’t have children. She stays in touch with her son and visits him a few times a year. While her job fulfills her, she’s adamant that she doesn’t want the responsibility of a child beyond a pregnancy—or beyond donating her eggs for IVF cycles, which she’s done 14 times since she was in her twenties. When Reeder’s not pregnant, she drives heavy machinery for a private logging company. She uses the money from her baby-making side hustle to travel to places like South East Asia and Zanzibar, where she has also donated her leftover breast milk to an orphanage.

When she met Tory online, Reeder was carrying a baby for a wealthy couple she met through an agency. For medical reasons, the mother couldn’t become pregnant, and with the help of a fertility doctor, the intended mother and father created embryos through IVF that were implanted into Tyra’s uterus. The couple approached an agency that matches and brokers deals between surrogates, egg donors, and intended parents. The agency suggested pairing them with Tyra after assessing everything from her lifestyle to her psychological health. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s guidelines recommend that a surrogate should have one proven healthy pregnancy under her belt, a promising sign of a complication-free pregnancy and birth, and the fact that Reeder had already had one child was enough for her to make the cut.

“You’ve got to watch out for guys that just like pregnant women as a fetish.”

After the agency made the match for a flat fee, a lawyer stepped in to secure the contract and ensure that the family and Tyra were on the same page with the financial arrangements, her diet, and other behaviors needed to support a safe pregnancy. In some states, for example, the law says that neither side gets to change their mind, and the intended parents are legally and financially responsible for the baby no matter what. “My job is to make sure everyone is in alignment because some agencies are more careful, and some are less careful about the matches,” says Deborah H. Wald, a lawyer whose expertise is assisted reproduction and parentage law. Wald routinely handles cases like Reeder’s and the couple whose baby she carried, but she was not involved in this one. The couple paid Tyra close to $50,000, including the fee from the agency. Tyra also received perks like maternity clothes and a food budget.

After two weeks of online chatting, Tyra and Tory, whose job is to stripe roads for the Oregon Department of Transportation, decided to go on their first date at her favorite local restaurant, McMenamins, a popular Oregon chain. “You’ve got to watch out for guys that just like pregnant women as a fetish… the ones that ask you, ‘Oh, are you going to pump milk after?’ It’s like, oh, you’re weird!” she says during a recent interview. “But this guy was different. He was really kind and soft-hearted. He said, ‘If I [were] a woman, I would want to do that for people.’”

The date went so well that neither of them remembered to eat. She liked that he was quiet and reserved, and they bonded over the fact that they both liked to cook Indian food. They also discovered a somber shared background of difficult parents. “On that first day, we started making plans to spend three nights together in his timeshare on the coast,” she says. In those three nights, the two fell in love, and three months later Tory was rubbing Tyra’s back as he stood with her in the delivery room, along with Tyra’s mother and the couple whose baby she was carrying, as she delivered them a healthy baby girl. A few months after the delivery, Tory and Tyra traveled to Zanzibar, where he proposed, and then soon after that they got married on the Oregon coast beach where they first fell in love. Tyra wore a garland of white roses and a long lace white gown.

In addition to her surrogacy work, Tyra estimates that she’s donated hundreds of eggs through the years that now sit frozen in little metal canisters in a storage facility. She made $8,000 a cycle and knows of at least 27 children conceived with her eggs. She doesn’t know the fate of all her eggs or the details of all the babies born of them, but she loves that her DNA is part of so many different family trees. She stays in touch with a few of the families. Three years ago, she met a lesbian couple who carried to term embryos conceived with her donated eggs. One of the moms gave birth to twins, and Tyra closely follows their lives on Facebook. The twins are 2 years old now. “I think one looks like me and the other looks nothing like me,” she says. “I’m planning to stay part of their lives.”

She also knows of twin boys born to an Italian dad. “They have green eyes and live in Italy,” she says. “There’s a little girl. The family sent me pictures, but I have not gotten one in a couple of years.”

A few years earlier she carried a baby for another wealthy couple that she would visit with her mom for a week every month to donate breast milk. They’d talk regularly about parenting tips. “My mom had seven children, so the dad liked our advice,” she says.

When it comes to stories about prolific gamete donors, it’s typically sperm donors and sperm banks who get the attention for producing donor siblings families in the dozens—and sometimes in the hundreds. In recent years, stories have surfaced about donor siblings connecting through private Facebook groups, and often finding their donors through DNA tests. Who can forget the 2013 Vince Vaughn comedy, Delivery Man, about a childless man having a midlife crisis who discovers that he had fathered over 500 kids conceived with sperm he donated in his youth. These are the extreme consequences of the age of “collaborative reproduction,” a term coined by the late John Robertson, a law professor and bioethicist at the University of Texas at Austin, to describe the expanded array of civil rights for LGBTQ+ families, lifestyle choices, and medically assisted methods of reproduction available to 21st century families. A large and growing component of collaborative reproduction is the increasingly open roles that surrogates and gamete donors often play in these modern families.

It’s less common, however, to hear stories of such prolific egg donors like Tyra. At a time when so many Millennials like her have become less interested in marriage and children and are also delaying having children for their careers, she is a new kind of female fertility archetype: nurturing and distant at the same time. She fulfills her sense of altruism and her desire to procreate, but in a directly transactional way, selling access to her body and body parts for her own financial gain and freedom. “I’d say it’s 50 percent business, 50 percent having a purpose,” she says. “I never fall into a career. I always thought I’d be a professional athlete between volleyball and golf. And I got my pilot’s license at a young age, but I never fell into my niche. I feel like maybe procreating for others is it.”

Collaborative reproduction is also creating a new economic class division of those who can afford certain services and those who cannot.

That she stays in touch with some of her offspring may be a reflection of her biology. Eggs are larger than sperm because they contain a nucleus and cytoplasm, so each egg represents a greater investment of energy and materials. They are also more precious. A single semen ejaculation will typically contain hundreds of millions of sperm whereas even the most fertile woman will ovulate no more than three or four hundred eggs in her lifetime. From an evolutionary psychology perspective, this may explain why females typically spend more time caring for their offspring than males—though cultural norms also play a role, and the fact that Tyra is so engaged with several of her biological offspring may be more a reflection of her personal values and experiences than any underlying biology.

While this societal shift toward collaborative reproduction is expanding the possibilities for families, there is at the same time a potential dark side to Tyra’s job. Collaborative reproduction is creating a new economic class division between those who can afford certain services and those who cannot—and between the intended family and the worker–provider surrogates and egg donors, whose choices are driven in part by altruism, in part by financial need..

The first child conceived by donated egg was born in 1984. Since then it’s a growing part of the fertility industry, and today, many young women are lured, often through Facebook ads, into selling their eggs to pay for college or to pay off college loans. While there are many online groups that help women navigate the challenges of the in vitro cycles they go through to get their eggs, there is not much regulation of the industry except basic screening of donors by fertility clinics on their medical and genetic histories. For example, most fertility clinics have policies that donors can’t have any criminal record or a history of drug use, even antidepressants. Often agencies ask for their SAT scores or their college records—an Ivy league degree can command up to $50,000 for a donation. So Tyra’s job indeed raises questions about female exploitation by fertility clinics and egg donor and surrogacy agencies who have been known to take advantage of young donors. “Some clinics just push them through, overstimulate them to get more eggs, use hormone protocols (like hCG triggers) that increase risk for complications, and don’t follow up with them post-retrieval to make sure they’re OK,” says Diane Tober, an associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco Institute for Health and Aging and author of Romancing the Sperm: Shifting Biopolitics and the Making of Modern Families.

For her book, Tober in collaboration with other researchers at UCSF launched a large-scale research project on egg donors called the The Ovado Project. The study examines people’s decisions and experiences surrounding egg donation and egg freezing from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, sexual orientations, and gender identities. The goal is to help improve information for those considering these reproductive technologies to better assess their choices as well understand the long-term risks and benefits. “It’s important that the agency and the intended mother see her as a partner in the process of creating her family and look out for her interests as well,” Tober says.

As one safeguard against the exploitation of fertile female egg donors, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) has a 6-cycle limit guideline. But clinics do not consistently follow those recommendations. A number of donors in Tober’s study have undergone 10–19 donation cycles. “This is excessive, especially given that there is no longitudinal research on the impact of the drugs and procedures on donor health,” she says. “Tyra’s story, like others in my study, points to the need for a registry to not only track the number of cycles per donor, and better adhere to ASRM guidelines, but also to track the number of children per donor and donor health over time.”

The issue of safeguarding against exploitation also applies for surrogacy, which is why most surrogacy agencies recommend that a surrogate limit the number of her pregnancies to no more than four times. Yet, according to Tober’s study, many fertility doctors and surrogates ignore these recommendations and push the limits of their bodies for financial gain. Some countries have enacted policies to counter that ability. In 2015, India, which used to have a thriving international surrogacy program, placed restrictions on the program because of popular protests led by women’s rights activists who pointed out that these programs were putting poor, uneducated women at risk of exploitation by the rich. Many of these women lived in substandard housing that were essentially foreign baby mills. Now surrogacy is only available to Indian couples or single people who need a surrogate to carry a baby.

Tyra says she has never felt exploited by the families with whom she works. She is currently six months pregnant, carrying a younger sibling for the same couple the agency paired her with just before she met Tory, and the baby is due in October. For this pregnancy, however, she broke ties with her agency and decided to work directly with a lawyer, so she could make more money. “I did 14 egg donations through the agency and two surrogacies, and I just had a moral stopping point because they asked me to do the second baby four days after I had the last one,” she says. “I didn’t like how much the agency charged the parents. And all the woman who ran the agency did for me was book me a couple of plane tickets and occasionally ask how I was doing.” She also bought Tyra a purse when she delivered, which Tyra didn’t use for all the money she just got paid. “It was a dumb gift,” she says. “I don’t even like designer stuff. I gave it to my niece.”

She admitted that she is more tired this time around, and she wonders if it’s because she is older. It will be her last job as a surrogate, and she no longer donates eggs. She and Tory just celebrated their two year anniversary of their first date and recently renovated the kitchen of their house. The couple gave them a $500 gift card they used for the counter backsplash. “I’m happy to be nearing the end of this career,” says Tyra. “It’s been the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done, but also the hardest. If anyone else had asked me to carry again I would’ve said no. But I love the idea of their daughter having a sibling!”