Growing interest in psychedelic therapy reveals two different visions of the future: one of spiritual interconnectedness and one of sober neurochemistry.

Two competing visions of the future of psychedelics reveal much more than a mere debate about drugs—legal or otherwise. They symbolize larger ideas whose evolution reflects how we perceive ourselves at this moment in history, and what societal changes could result.

On one side is a scientific view, where psychedelics are simply chemical compounds affecting the brain which, in itself, determines the emotions, motivations, perceptions, and actions of the person. In this “medical model” worldview, the mind is the brain, and a person is neither more nor less than the sum of their complex biological parts, which we can increasingly map, monitor, and alter with precision.

On the other side is a view of psychedelics that pays homage to the ancient ceremonial significance of these drugs, while also responding to our contemporary era. Under this “healing model” worldview, rules about morals and behavior are no longer imposed from above—not by God, the state, or corporate entities. Instead, they evolve in the same way nature evolves, through dynamic systems of interaction. That non-hierarchical interconnectedness drives decentralized, blockchain-powered concepts like Web 3.0 and cryptocurrency. It’s also the force governing the spread of COVID-19 and the effects of global climate change. Psychedelics bring those hard-to-see forces to light.

The chemical view

Statues of the Buddha line the window ledge of Bryan Roth’s office at the University of North Carolina. The psychiatrist and pharmacology professor invented a biological tool called DREADDs, which is now used in neuroscience labs across the world. “My lab invented it because I wanted to understand how psychedelics work,” Roth says.

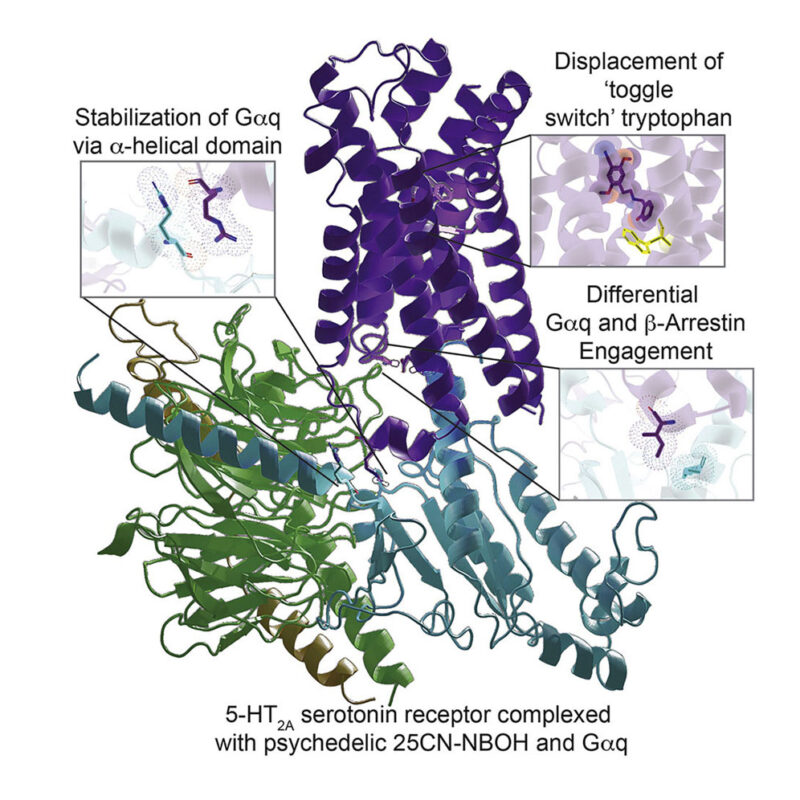

The acronym, DREADDs, is short for Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs—a name that describes the way the tool works. Essentially, Roth created DREADDs by designing a neural receptor that no chemical in the human body could bind to; he then engineered the sole chemical capable of binding to that receptor. This created a biological switch that Roth could control, allowing him to turn neurons on or off, causing a cascade of reactions. The receptor he targeted was the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), a common class of proteins found in the human brain, and the one to which LSD binds.

In effect, Roth’s first DREADD let him precisely map the circuits and cells responsible for LSD’s action.

“A lot of people were trying to make these creatures,” Roth says, referring to DREADDs. He succeeded where others failed because he used a then-new method for drug discovery, called directed evolution. The power of this method is that scientists, not nature, decide which traits should survive through the evolutionary process.

Twenty years after Roth evolved a human protein through directed evolution, scientists are using the method to create everything from biodegradable plastics and clean energy to new medicines. The technique has gotten exponentially more sophisticated with advances in machine learning. The brute-force approach Roth used to create his first DREADD has been streamlined through AI. Instead of generating compounds in yeast, he can do so through his computer platform, called Ultra LSD. “We’re able to access this huge chemical space,” Roth says, since the compounds he’s evolving “don’t exist in the physical universe”—not until he chooses which ones to synthesize.

Roth is choosing LSD-like compounds whose binding actions cause the growth of dendrites—the neuronal spines that reach across the brain, connecting to other neurons—but don’t cause hallucinations.

“The idea of harnessing neural plasticity to rewire neural circuits is a paradigm shift in neural psychiatry.”

This is the nub of the chemical view of psychedelics: that psychedelics are effective at treating mental illness because they induce dendritic growth, not because they initiate the experience of a trip.

Roth readily admits that psychedelics have therapeutic benefit, as shown by recent clinical trials. “It’s a gigantic effect,” he says. “They’re going to revolutionize the treatment of mental illness. No question. But wouldn’t it be great if you could just take a pill and the next day your depression would be gone? I mean, you may miss out on the mystical experience, but you wouldn’t be depressed anymore.”

Through Ultra LSD, Roth sought a drug that could do just that. He examined 11 billion chemical compounds, searching for those that could induce dendritic growth without hallucinations. After choosing a handful of the most promising candidates, he synthesized the drugs and tested them on mice. The results are currently under embargo since publication is pending in a peer-reviewed journal. All Roth can say is that he’s “very pleased” with the outcome.

Plastic fantastic therapeutics

Non-hallucinogenic psychedelics have been dubbed “psychoplastogens” by professor David Olson, a biochemist at UC Davis and co-founder of Delix Therapeutics, a company developing new drugs in this class for therapeutic use.

In stress-related conditions like depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse, dendrites are often seen to “shrivel up,” Olson says. “If you think of neurons like a tree,” where the branches are dendrites and the leaves are synapses, “you basically lose all your leaves, and the branches get trimmed.” The neurons become less robust in communicating across the brain’s various regions. Psychedelics’ ability to rapidly regrow neurons, known as “plasticity,” inspired Olson’s work on psychoplastogens.

“The idea of harnessing neural plasticity to rewire neural circuits is a paradigm shift in neural psychiatry,” Olson says.

But plasticity isn’t uncommon, says Alex Kwan, professor of neuroscience at Yale University. Other psychoactive chemicals like cocaine and nicotine induce neural plasticity—as do ordinary neuronal development and lifelong mental processes like learning. Yet psychedelics are unique. “There’s something about psychedelics,” Kwan says. “What regions is it targeting, what cells it is targeting, why is this plasticity different?” To find out, researchers need to map the regions in the brain that feed all those new dendritic spines. That’s not yet possible, although Kwan is collaborating with an optical engineer to design a microscope to image neurons across the three-dimensional space of the brain, taking various simultaneous views to follow the elaborate, distributive structure of dendrites in a way that can’t be done with two-dimensional images. “This imaging technology—looking at a whole dendritic tree in a live animal—will give us a lot of new insight into how these drugs work.” Which, in turn, will shape the questions researchers ask, Kwan says.

The new microscope won’t be operational for a few years, but advances in microscopy have already altered researchers’ fundamental knowledge of the brain. Roth capitalized on a cutting-edge technique called cryo-electron microscopy to see LSD actively binding to its receptor—a goal he’d had since the 1980s. Even before this, though, Roth made the cover of Cell for his work on LSD binding. In describing his work at a conference, he mused that imaging data might make it possible to create a chemical analog of the psychedelic compound that would be non-hallucinogenic.

Representatives from DARPA were in the audience. Roth soon got a call from the government.

Roth says he’s “agnostic” about whether non-hallucinogenic psychedelics will have any therapeutic benefit. Only clinical trials can answer that question, he says. Even so, he’s optimistic, especially because of one fundamental idea: “LSD is just a drug,” he says. “It’s a drug. And when it interacts with neurons, those interactions are all biochemical.” In other words, the mechanism through which LSD works isn’t an “interaction with dark matter in the cosmos… It’s just interacting with the receptor.”

The interconnected view

For Rick Doblin, the director of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), the most important interaction that can take place in a psychedelic experience is not between a drug and its receptor or between the neurons in the brain, but between two people: the person taking the drug, and the one guiding the experience—a therapist, friend, or religious leader, for example. Doblin is arguably the person most responsible for the reinvigoration of clinical research into psychedelic therapy because he was the first to systematically pursue a long-term plan to convince the FDA of the efficacy of these drugs according to the medical model.

Doblin has been working toward the legalization of psychedelics for decades, overcoming regulatory barriers by designing studies that address potential roadblocks to legalization, providing evidence that clears a path for further research or policy change. After forming MAPS in 1986, Doblin submitted five different protocols for MDMA clinical trials—and was rejected each time. He then stepped back, deciding to fund animal-toxicity studies while also supporting research on human safety, finding people who’d used MDMA to voluntarily undergo spinal taps to show that MDMA hadn’t adversely affected their health. These basic building blocks paid off, with the first FDA-sanctioned, phase 1 clinical trial with MDMA approved in 1994.

Doblin has shown an ability to ease institutional resistance, in part by forging alliances with organizations like the Department of Veterans Affairs, a body that’s diametrically opposed to the counterculture narrative of psychedelics’ past, but shares MAPS’s commitment to improving mental health treatment. Doblin can also connect with audiences from the FDA and members of Congress to the CBS Sunday Morning show and the magazine GQ. He comes across as honest and genuine, not hiding any ulterior motives or seeking to profit from the booming business of psychedelics.

Although MAPS’s public statements have focused on clinical trials and research, Doblin has never concealed the fact that he seeks more than the legalized prescription use of psychedelics for specific disorders like PTSD or anorexia. He’s always sought the legal and cultural acceptance of psychedelics—“it’s just that nobody paid attention until now!” he says. Nobody thought the day would come when psychedelics would be embraced by the mainstream. But somewhere in the past twelve months, he says, that day arrived.

Three windows into society’s mind

Doblin portrays three possible ways through which psychedelics will enter mainstream culture. The first is a continuation of religious freedoms enshrined in various U.S. laws, including the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993. These laws grant exemptions to religions such as Santo Daime, whose ceremonies are centered on the drinking of ayahuasca tea.

The second way has attracted the most attention: psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy, where a person is prescribed a treatment for a specific disorder like PTSD or anorexia. The prescription covers the drug itself, but also multiple therapy sessions to “integrate” the experience, helping people incorporate the insights gained so they can apply that knowledge in their everyday lives.

Doblin, who says integration is essential to psychedelics’ therapeutic effectiveness, is one of many people advocating for health insurance coverage for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

Not everybody has insurance, though, and the therapy is expensive. That’s why psychedelics need to be legalized, Doblin says: “Legalization gets around the fact that one-quarter to one-third of people in America don’t have insurance.”

In Doblin’s conception, a person would obtain a license after undergoing a supervised trip led by a certified therapist who would also provide information on safe use for future trips. Although this licensing system could be quite expensive, Doblin insists the fee would be low cost, if not free, subsidized by taxes collected on the legal sale of psychedelics. A similar system was put in place in Michigan when marijuana was legalized: $20 million from sales of the drug are earmarked, in the first two years, for research into PTSD treatments for veterans.

In one important way, the legalization of psychedelics would differ from that of cannabis: People would be able to use the drugs on-site. That would enable the spaces to become community hubs, developing their own vibe, some evolving into wellness clinics providing therapies of all kinds, others hosting arts events and dance parties, others acting as places for political engagement and training—whether about climate change, poverty, or even issues surrounding equity and diversity in the psychedelic community itself.

That particular notion—that a psychedelic space will arise organically, without top-down dictates—aligns with the views of Franklin King, psychiatrist and director of training and education at the Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics at Massachusetts General Hospital. He uses psychiatry as a microcosm representative of larger trends in society.

“I just came from the psychiatric emergency room,” he says, describing a scene where people come into the hospital and lose control of what happens to them. “I basically tell them what they’re going to do—you’re going to be hospitalized, you’re going to take this medication—and they receive it. That’s the medical model,” King says, “and it’s broken.”

The “interconnected” view of psychedelic therapy is premised on the fundamental ethos that each patient has an innate capacity to heal.

In that traditional medical model—the “chemical” view of the future of psychedelics—the doctor prescribes a treatment, often in the form of a drug. “The drug isn’t unlocking anything intrinsic in a patient, it’s just doing something biological to treat symptoms.”

By contrast, the “interconnected” view of psychedelic therapy is premised on the fundamental ethos that each patient has an innate capacity to heal. “The medicine unlocks it, the therapist supports it. But it’s really a process that comes from the patient,” King says. To him, this is a prime example of society’s rejection of hierarchical structures of power, where truths are dictated from above. “It’s in politics, it’s in cryptocurrency, it’s in grassroots movements organized online. Psychedelics are a big part of that change.”

Zeitgeist drugs

The terrain of psychedelic use is now in flux, but the systems for bringing these drugs to the mainstream are likely to solidify by the end of the decade, with inklings coming in the next two years. By then, the FDA is anticipated to approve MDMA and psilocybin for prescription use: If current clinical trials proceed as planned, the FDA will consider an application to approve MDMA for treating PTSD in 2023, using the protocol that includes integration therapy, and will consider applications regarding psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder not long after. As for non-hallucinogenic psychedelics, both Olson and Roth expect phase 1 trials to begin in 2022.

The two visions detailed here could easily coexist, with one dominating the mindset of the medical profession and capturing the popular imagination while the other burbles along in the background.

Regardless of capturing the zeitgeist, these drugs are attracting investment interest. With the industry expected to reach $7.5 billion globally by 2028, investors are rushing into the field—and have no lack of companies to choose from. Big pharma, including Johnson and Johnson, is in the game but on the back foot as startups race forward, developing synthetic analogs whose properties range from non-hallucinogenic, such as those developed by Delix, to short-acting, such as some developed by current front-runner Compass Pathways. Patent disputes are already brewing as companies seek exclusive rights to everything from the drugs they develop to the methods of production—and even the music played in therapy sessions.

But business dealings are not new. What’s new—at least in the intensity and clarity of the conflict—is the division between neuroscience and the experiential. The chemical versus the interconnected.

The proponents of each future-of-psychedelics worldview don’t dismiss the other side’s position, they just see it as irrelevant to the predominant trend in society. Olson points to the millions of people who could benefit from synthesized drugs inspired by the neurochemistry of psychedelics. Doblin’s vision, by contrast, encompasses both hemispheres of the globe—not just the brain—maintaining that psychedelics manifest an understanding of the interconnected nature of environments, people, and societies. For him, psychedelics derive their power from the physical experience of the body in the world.

Ironically, this is also how Roth conceives of therapeutic change. When asked about the Buddha statues in his office, he mentions his Zen meditation practice, which typically produces benefits over time, he says, “and by having an entire lifestyle devoted to being a better person.” The process isn’t easy, he adds, saying, “Meditation isn’t user-friendly!”

And this might be the crux determining which of these visions shines brightest, and whether one (or both?) is just a flash in the pan. Namely, what will people do with the insights gained from these drugs? Will psychedelics and their non-hallucinogenic analogs invoke a change in behavior, on an individual and societal level? Or will it all be in our heads?