Demand from body builders, neonatal intensive care units, and Big Pharma fuels synbio substitutions for the goodness of breast milk.

Imagine we created a dream food—a superfood—something which, if consumed more widely could reduce cancer risk, boost our immune systems, and increase our overall health. What if millions of years of mammalian evolution has already figured out the recipe? That superfood is human breast milk, and for a growing number of scientists, marketers, and biohackers, it could be a white liquid gold.

Human breast milk provides unparalleled advantages both to babies and mothers, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The advantages for the baby are obvious. Mother’s milk is packed with all the macronutrients an infantile mind and body needs—the rich fats, carbohydrates, and proteins—as well as micronutrients like essential long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, growth factors, infection-fighting antibodies, and immune system cytokine proteins. Studies have shown breastfeeding reduces the risk of sudden infant death syndrome, asthma, obesity, gastrointestinal problems, and infections. Furthermore, a 2020 Irish study has confirmed that human milk has a unique microbiome and includes stomach-protecting probiotics like Bifidobacterium breve and Lactobacillus plantarum.

Breastfeeding mothers, in turn, experience reduced high blood pressure and increased protection against ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and type 2 diabetes.

For all these reasons, enthusiasm for human breast milk abounds—at milk banks, neonatal ICUs, biotech companies, Big Pharma, among bodybuilders, and anywhere YoPros (young professionals) go to down supplements. They all seem to want a reliable supply of the precious commodity, and our scientific understanding of actual and synthetic breast milk is maturing rapidly.

Bodybuilders versus babies

Interest is not new. Ever since the 1970s, when former Mr. Universe, screen actor, and later California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger disclosed that breast milk was part of his routine, bodybuilders seeking to quickly increase their body mass and athletes trying to improve their endurance have acknowledged its value.

But do such nipple tipples come at the cost of depriving babies that desperately need it?

Austrians were the first to establish milk banking at the beginning of the 20th century as an alternative to wet nurses, and the first milk bank of North America opened in Boston in 1919. Then, propelled by activist mothers and advocates of breastfeeding, milk banks quickly spread across the planet until the 1980s, when the opening of new banks was slowed because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Milk banking has seen a resurgence in the last two decades with the advent of the digital age and the introduction of peer-to-peer bulletin boards like Facebook’s Human Milk 4 Human Babies, which is designed to connect breast milk donors with local babies who need the milk. But black-market sales to adults and other abuses are growing. Because peer-to-peer networks sidestep intermediaries by design, putting donors in direct contact with buyers, they can increase opportunity for exploitation.

As recently as the end of 2021, articles in the Chinese and Indian press have denounced the commodification of human breast milk and the emergence of a quasi-black market leveraging websites created for mothers of newborns to donate or sell their breast milk around the world. At least some of these peer-to-peer marketplaces are allowing bodybuilders and all sorts of other adults chasing the latest fad du jour to purchase the precious liquid, driving up prices and making it harder for even hospital neonatal ICUs to obtain it.

All that is soon to be a thing of the past, says Calvin McIntyre, bodybuilder and founder of Bodies and Beyond, a gym in Petersburg, Virginia, that places a high value on the communion of nutrition with physical training for effective and safe bodybuilding.

“In some sense, the studies, the tests, and the research conducted with human breast milk taught us a lot about how to increase body and muscle mass safely, more effectively, and to avoid getting the bad rap of stealing the food out of the mouth of premature babies,” McIntyre says.

In 2019 the United States hit an all-time high of 450,000 premature births.

In researching this article, proto.life explored several sites devoted to breast milk, including Only the Breast, the milk-sharing site Eats on Feets, and Facebook groups like Mom’s Liquid Gold. Even though members on at least one one of these sites were openly advertising they would sell human breast milk to adults for their own personal consumption, a representative of another breast milk exchange emphasized her organization is adamantly opposed to the practice. “We do not support the selling and buying of breastmilk on our network,” Eats on Feets founder Maria Armstrong said in an email. “We simply offer a platform for the non-commercialized sharing of breastmilk.”

But there’s no question that online breast milk banking is exploding. In 2019, the Human Milk Banking Association of North America (HMBANA), a U.S.-Canadian association of nonprofit milk banks, distributed 7.4 million ounces of human milk to NICUs in the United States, increasing nearly seven times over the amount distributed initially in the year 2000. Over the same two decades, the organization expanded from 10 regional chapters to 30, and private online transactions for human breast milk grew from about 20,000 to more than 50,000 per year.

“Donors and sellers should consider that the milk donated to [our] banks goes to the most fragile infants,” says Lindsay Groff, executive director of HMBANA. However, she underplays the relevance of the sales phenomenon, pointing instead to the most significant element of crisis in the system—premature babies. In 2019 the United States hit an all-time high of 450,000 premature births—defined as babies born before 37 weeks gestation (and sometimes as early as 20 weeks or less). Worldwide, preterm birth is a major problem, and some 15 million babies are born too soon every year, making it a major cause of childhood death and disability.

“This number has been growing steadily in recent years, particularly in emerging countries, and among the [Black] community and other ethnic minorities in the U.S.,” states Bruce German, director of the Food for Health Institute at the University of California, Davis.

Not only is the number of preemies growing, but German notes that due to malnutrition, poverty, and other social ills, U.S. mothers of premature babies are often young, food insecure, and homeless—making them unable to produce enough milk. Compounding the shortage, the COVID-19 pandemic has reduced donation opportunities and impacted the distribution of donated breast milk.

A market formula

Some worry that if interest in acquiring human breast milk as a raw ingredient within the nutraceutical and pharmaceutical industries grows, it could propel the price of what is already a pricey ingredient—up to $3 per ounce on social networks—into the stratosphere. If that happens, it would transform the donation of one’s breast milk from a symbol of motherly altruism toward other mothers in need into a sign of a booming gig economy—though some experts dismiss the notion.

“It is true, the valuation of a scaled-up [human breast milk] sector can reach in the billions per year,” German says. The journal Food and Nutrition reported that the U.S. market for breast milk substitutes, like store-bought formula, had already reached $40 billion dollars in annual sales by 2013—and the global market is currently projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate 10.2 percent until 2027.

Nevertheless, German is confident that the industry does not compete with human breast milk banks because it doesn’t need to. He believes that the industry’s renewed interest in human breast milk has given us better insight into how nutrition works, the interaction of nutrients with the gut microbiome, and how to leverage the enzymes, disease-fighting antibodies, growth factors, essential fatty acids, and other biological factors contained in human breast milk to treat degenerative conditions in the adult population—but we don’t actually need real breast milk to exploit this knowledge.

“Concurrent developments in the biotech and pharma industry allow for the possibility of creating these factors in the laboratory,” German says. With modern fermentation, along with cutting-edge synthetic biology, these breast milk molecules can be produced in the lab and added to food formulation for the general public without ever consuming an ounce of actual breast milk, explains German.

However, there’s still a steep hill to climb. Not everything that’s healthy inside of breast milk has been identified, and some of the factors that have been identified are hard to replicate in the laboratory.

Many of the pro-health factors found in human breast milk belong to a class of complex sugar molecules known as oligosaccharides. They are the third-largest solid component of human milk after lactose and lipids and are 300 times more concentrated and structurally more diverse than cow’s milk. Germany-based chemical behemoth BASF is the world leader in the production of one of these oligosaccharides, called 2’-fucosyllactose (2’-FL), which is among the most abundant ones found in human breast milk. According to BASF, these chemicals help with human intestinal integrity, cognition, and memory, and the company is currently exploring the potential of 2’-FL in adult nutrition.

“We’ve shown in animals that specific [oligosaccharides] can be used to treat diseases like heart attack and strokes.”

But BASF’s product is only one of more than 150 different oligosaccharides that have been identified in human milk so far, and we are only beginning to understand the biological effects many of them have on the human body.

More challenging still is making them synthetically. Although some oligosaccharides can be produced en mass in laboratory fermenters by genetically modified bacteria or yeast, most cannot be. Synthesizing human milk oligosaccharides is complicated because many of them are the end products of a long cascade of subtle, chemical enzymatic reactions that take place in a woman’s body, but remain challenging to replicate in the laboratory. For example, chemists at Vanderbilt University took about two years to figure out how to synthesize lacto-N-tetraose, one of the simpler human breast milk oligosaccharides.

Alexei Demchenko, a carbohydrate chemist at Saint Louis University in Missouri, is developing an automated human milk oligosaccharides chemical synthesizer based on high-performance liquid chromatography that could do for decoding breast milk what the PCR cycler did for sequencing the human genome.

“Our target is to synthesize all the core structures of human milk oligosaccharides,” says Demchenko, “with the press of a button.”

Lactation in a bioreactor

Far from trying to solve and replicate the complete, complex mixture that is mother’s milk, many researchers and companies are focused on one component or another.

At the University of California, San Diego, Lars Bode, whose primary research concerns necrotizing enterocolitis, a severe newborn gastrointestinal problem, is also experimenting with human breast milk oligosaccharides to treat and prevent adult diseases involving chronic inflammation. “We’ve shown in animals that specific [oligosaccharides] can be used to treat diseases like heart attack and strokes,” states Bode in a video presentation for the 94th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop.

Private companies are taking similar approaches. For example, TurtleTree, a Singapore and Sacramento, California, biotech startup, manufactures lactoferrin using microorganisms in a bioreactor. Lactoferrin is a multifunctional human enzyme found in breast milk and is specifically abundant in colostrum, the first milk a mother produces after her baby is born. Sold widely as a dietary supplement, lactoferrin has known antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties.

Other companies seek to produce several different components of breast milk at once and then mix them. For example, the New York State-based startup company Helaina attempts to reproduce every significant known part of human breast milk separately in the lab and then mix them to form a human milk-based formula.

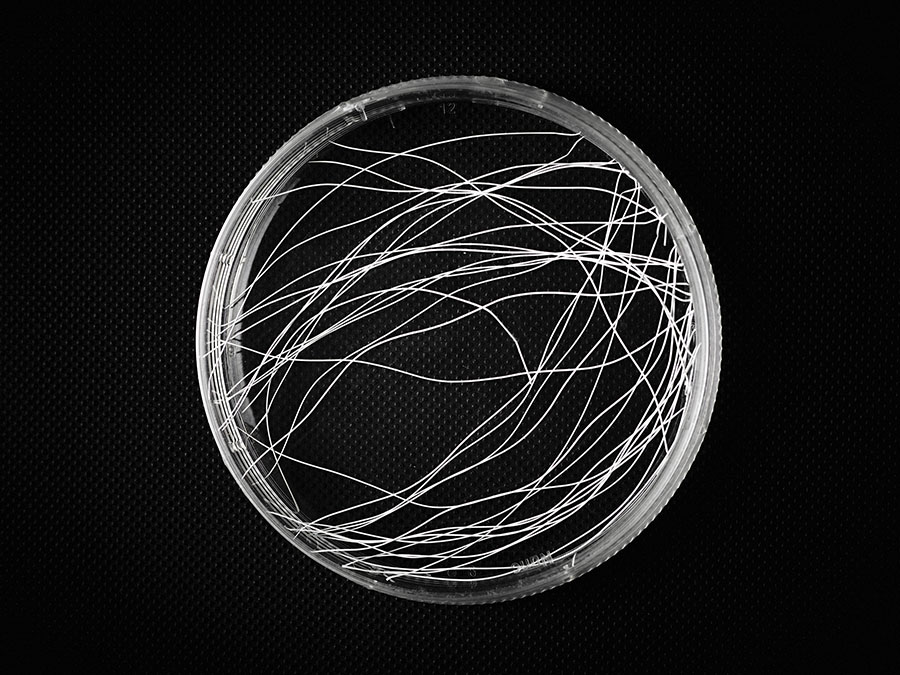

There are also citizen-driven organizations like Counter Culture Labs of Oakland, California, led by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory computational biologist Patrik D’haeseleer and backed by IndieBio. They attempt to produce synthetic human milk and foods like cheese based on breast milk. Their mission is to put the genes for making quasi-human milk within reach of hobbyists and professionals alike so that they can make cheese from any animal for which they have a genome sequence, “including narwals and unicorns,” D’haeseleer says jokingly.

The frontier of human breast milk research goes well beyond finding ways to produce components of human breast milk grown in yeast or bacterial cells. Some are now producing them using cultured human breast cells. TurtleTree and North-Carolina-based Biomilq, which touts its “breakthrough mammary biotechnology,” are experimenting with human mammary epithelial cells grown in a bioreactor. Their innovation is organizing these cells in layers over a bath of nutritional factors, partially mimicking actual breast tissue, which allows the cells to absorb nutrients fed by the nutritious bath below and secrete a milk product that is siphoned off above.

The goal for Biomilq, as well as for scientific researchers like German, isn’t merely to produce something like human breast milk but rather to recreate every bioactive present in actual breast milk. If they can do this—Biomilq states on their website—it will empower parents with an additional nutritional option “that’s as close to breast milk as possible and cultivated under safe conditions.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated on Feb. 19, 2022 to correct Maria Armstrong’s name and to clarify her organization’s strong opposition to the practice of buying and selling breast milk on its site.