BOOK REVIEW

4 Books to Read Right Now

Mini forests, seed preservation, our synthetic biology future, and a comic on depression.

It’s summer time, and in these dog days of oppressive heat, threatening thunder storms, and looming vacations, it’s time to take a break and catch up on reading. With that in mind, I took a look at the books on my shelves and found four great ones to share.

Rage for the machine

“We’re on the cusp of a breathtaking new industrial revolution,” declare Amy Webb and proto.life friend Andrew Hessel in the opening pages of their new book The Genesis Machine (Hachette/Public Affairs), a deep dive into the promise of synthetic biology and all the economic, geopolitical, and social questions the new field raises.

Perhaps fittingly published the same year we celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of Gregor Mendel, the father of genetics, the book is premised on the bold promise that life will someday soon no longer be a game of chance “but the result of design, selection, and choice.” The authors imagine a world, which they say is closer now than ever before, where biological systems are programmed like computers, diseases are eradicated, species like the woolly mammoth are resurrected, agriculture is reinvented, meat and fashion are reimagined, the Earth is greener, and people live longer, healthier lives.

But if the book avidly explores the promise of synthetic biology, it doesn’t shy away from its “profound and problematic” implications along with the barriers for its adoption—misinformation, antiquated patent laws dating back to the 1700s, regulatory barriers, and public mistrust to name just a few. That’s one of the great strengths of the book. The problem of futurism is not with the future—it is with the futurists who have eyes too rosy and outlooks so positive they gloss over the fine and nasty details. The Genesis Machine does not fall into that trap. Although breathless at times as they explore the hope and promise of synthetic biology, the authors never ignore the possibilities of dual use, malfeasance, unintended consequences, stolen DNA and exploitation, increased disparities, and the politics of global competition between interests in the United States, China, the European Union, Singapore, and Israel.

One of the nice things about the book is its broken narrative approach. It starts with the past: a history of synthetic biology, tracing its origins to the discovery of synthetic insulin at Genentech in the late 1970s. It covers the race to solve the human genome in the 1990s and the discovery of CRISPR a few years later. It jumps around in time, from the 70s, to the 50s, to the 1830s, to the early 2000s, and back again to the 1970s, all without missing a beat. The second part of the book explores the present, beginning at the dawn of the COVID-19 pandemic and Moderna’s race to retool its mRNA technology to make vaccines. From there the book goes on to project the value of synthetic biology in future terms, comparing where the field stands now to where the telephone stood shortly after Alexander Graham Bell first demonstrated his prototype in 1877—a disruption that spawned a $1.7 trillion industry today.

The book ends with a series of recommendations, largely policy oriented. Some of these are expected, like banning gain of function research—while some are likely to create ripples of dissent among certain readers, like requiring licensure for doing DNA research. That’s not likely to sit well with biohackers. Also at the end of the book are scenarios of what they call the “recently plausible” ways synthetic biology could change our lives the next 50 years—from redesigning your baby to increasing longevity to giving you the ultimate yuppie dining experience in “ghost” kitchens with robotic staff. Folding a short stack of what are essentially science fiction chapters into an otherwise a straightforward nonfiction account of a subject is both fun and thought provoking, though the use of an alternative font in my advance copy was a little off putting.

Nevertheless the book remains, above all else, daring. The problem with synthetic biology, according to Webb and Hessel, is not playing God, which they argue we have been doing for thousands of years already. The real problem, they say, is that thus far we have done a terrible job of it.

When depression wags the dog

In addition to boldness in ideas, there’s something to be admired in a writer or artist willing to discuss their most intimate health problems openly, with no small amount of self-deprecating detail. This is especially admirable when they are discussing highly stigmatized conditions like anxiety and depression, which is what you’ll find in Rachael Smith’s Wired Up Wrong (Icon Books), which first appeared in 2017 and is published in paperback this summer.

The work is a deep dive into Smith’s life, which in modern, comic-book form captures the first two lines of Dante’s Inferno: “Midway along the journey of our life / I woke to find myself in a dark wood.”

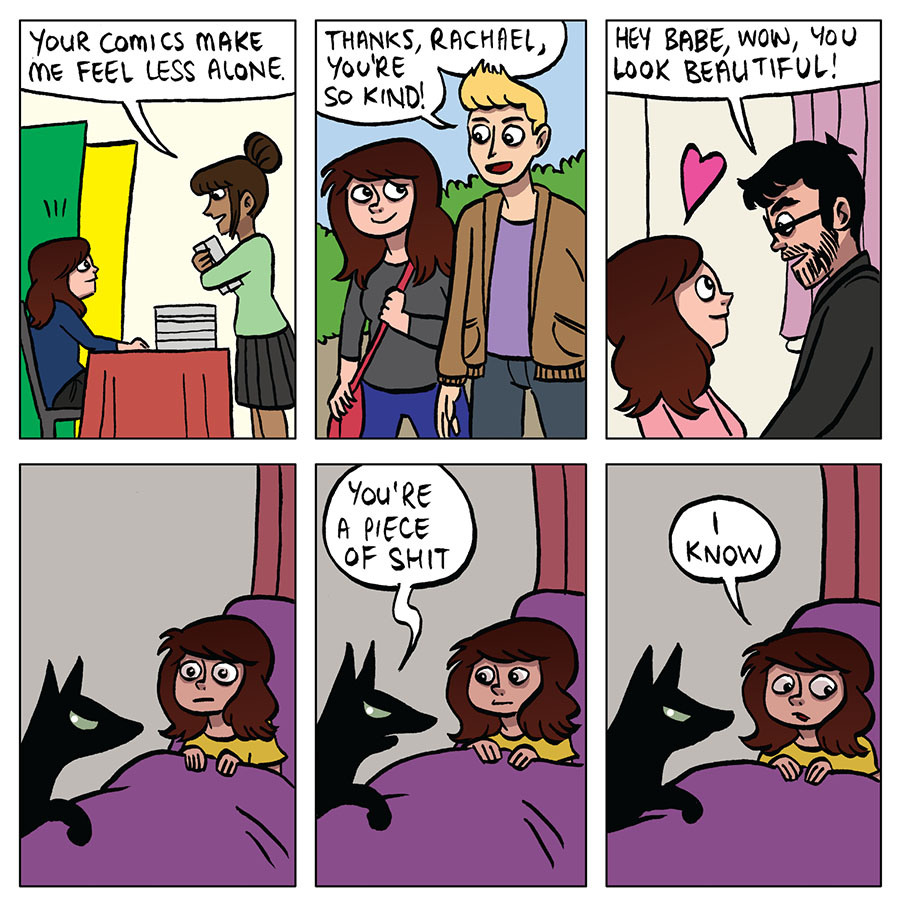

On the surface Smith has a rich life. She is a young, successful comic book artist. We meet her boyfriend Adam, her sweet cat Rufus, her strong and impressive mother, and a parade of 30-something friends. But from the start of the book, we also meet her depression, which Smith personifies as Barky, a mean-spirited imaginary black dog who lives inside her head. As you flip the pages and she goes about her day, the dog is constantly tearing Smith down and filling her with self-doubt. In one panel he criticizes her looks. In another he wakes her at 4am to gloat about her problems. Over and over, he appears to remind her that nobody likes her, and at times Barky grows to monstrous proportions, blocking her from leaving the apartment or wrapping his dark, furry body around her in more of a choke than an embrace.

The device is similar to the loud, angry voice of self-doubt employed in Justine Bateman’s dark indie feature Violet last year, and just like in that film, it works. The central tension in Wired Up Wrong emanates from the author’s confrontations with Barky, a corruption of the notion of man’s best friend that creates a more honest and intimate depiction of living with depression than we’ve seen before.

Smith says at the very beginning of her book that she is not a doctor and that her book is no substitute for seeking professional help. She encourages readers who may be depressed to seek professional help, and at the end of the book she lists a few U.K. sites and organizations where people can turn. Like her, I hope that by sharing her intimate personal history of her own depression Smith will inspire others to finally deal with their own mental health problems.

The mighty forest as a bite-sized hero

There’s nothing abstract at all in Hannah Lewis’s new book Mini-Forest Revolution (Chelsea Green), in which she makes a straightforward case for the “Miyawaki method,” a reforesting approach based on the work of the late Japanese ecologist Akira Miyawaki, who died last year. Beginning in the 1970s, he pioneered a way of creating small plots of forest based on densely planting native plants best suited for the climate. Proponents of his method claim it can yield a tiny mature forest within decades—as opposed to the centuries it would normally take to establish an old growth grove.

Mini-Forest Revolution is a treat to read because it’s beautifully written, and it takes the reader to plot after plot of tiny forest projects around the world, which Lewis calls “little beating hearts” of wildlife. The book goes from corporate compounds in Japan to the streets of Mumbai to the arid plains of northern Iran. We visit the coastal mountains of Cameroon and the hilly slopes of the Great Wall of China. We read about projects in the streets of Paris, on the industrial outskirts of Amsterdam, in working-class suburbs of east London, and on the grounds of a federal prison in Washington State. The book is an easy dive into applied ecology and a sobering look at deforestation and land degradation—and how they could be countered.

Reading the book, you quickly come to appreciate how in an era of short tweets and tiny houses, the Miyawaki method for making mini forests could be poised to become the next big small thing. It is also a good example of citizen science and community science because wherever these DIY ecology projects arise they seem to be met with armies of local residents volunteering to help. Describing those planting events is one of the real strengths of the book. I was struck by how one project took place in rural Indiana and offered family-fun features like face painting, cookout burgers, a petting zoo, and live music. That contrasted with a second project on the barren grounds of the Yakima Nation correctional and rehabilitation facility in Washington State, were prisoners in orange jumpsuits planted their mini-forest with not a snow cone in sight.

The practical-minded reader will appreciate the book’s how-to appeal. It offers a field guide to planting a mini forest at the end—things like how to form budgets and research which native plants to use—as well as Lewis’s own recent experience planting a mini forest in the French community Roscoff in Brittany during the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. I personally like how she quotes the 1980s band Talking Heads right alongside academics. In the same way a good book about food will make you hungry, this book will make you want to go out and plant a mini forest.

The secret lives of lost vegetables

It’s hard to imagine anyone going out and doing what Adam Alexander has done in the last 35 years—or even being able to try. He is living proof of the old cliché that everybody has at least one great book in them, and he says it was his lifelong love of gathering seeds and enjoying eating the unusual fruits of those efforts that led him to write his new book, The Seed Detective (Chelsea Green). Like the heirloom vegetables that are its subject matter, the book is strange and delightful. Part memoir, part sermon, it champions the environmental and culinary righteousness of heritage foods.

What makes the book so unique is that Alexander spent his career as a filmmaker, a job that took him to exotic locations around the world. It was in one such place in the industrial city of Donetsk, Ukraine, during a Soviet steel strike in 1988 that he discovered a rare red pepper called Capsisum annum, which he says changed his life, and his inner seed detective was born. For the next 30 years he has been a film and TV producer by day who chases down seeds on the side, “always on the trail of local varieties that, first and foremost, were delicious and which I could grow in my own garden,” he writes.

We follow him as he wanders through open air markets on the banks of the Mekong River in Laos, looking for unusual peas. We’re with him as he explores the high desert of New Mexico searching for rare blue corn. We read about his exploits in the ancient Roman city of Palmyra just before the start of the Syrian war, where he is stopped by lads with AK-47s and recovers a handful of fava beans he believes are descendants of some of the first domesticated crops 12,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent.

Today he says he has a collection of 500 vegetable seed varieties crammed into a couple fridges in his garage, and his new book is about some of his favorites among these. We read about the disputed provenance of the Daniel O’Rourke pea, an American cultivar named after an 1850s English horse and claimed by the Irish ever since. We discover how the United States pushed Peruvian farmers to stop growing coca (the plant used to make cocaine) in the 1990s, which is why the country is the number one producer of asparagus today.

Alexander has a delightful voice—even if he comes across as a bit kooky at times, describing at length how he talks to his plants every single day. Nor is this a straightforward narrative of his exploits and adventures. If anything, the reader may find themselves craving more of his personal narratives. That’s not to say there’s anything lacking in the book—it’s crammed with research into the cultural and horticultural history of the crops, as well as information on their modern agricultural and economic significance. He tracks references to his crops in Ezekiel from the Old Testament, Julius Caesar, Pliny the Elder, Charlemagne, and more modern writers. He traces each crop in time from their earliest known domestication in places like Afghanistan, Syria, and Peru to a cherished place in his small garden, and along the way it’s amusing to read about what Chaucer and Herodotus thought about lettuce or the possible genetic reason why Pythagoras hated beans.

His crops of choice are decidedly British—carrots, cabbage, broad beans (known as fava beans in the United States), Welsh leaks, asparagus, and more varieties of peas than I could count. It isn’t until the later chapters that we encounter the classic new world vegetables corn, chili, tomatoes, and squash—but by that point in my reading it was too late for them to satisfy my hunger. I had long since gorged on a plate of pole beans for lunch.