William Trubridge is shredding world records in free diving. Is the secret to his success lurking in his genome?

Part one of a three-part series. Part two is available here and part three is here.

In July 2016, William Trubridge, a champion free diver from New Zealand, floated on his back above Dean’s Blue Hole in the Bahamas, ready to submerge. For weeks, he had prepared for this record attempt, training in and out of the water, and taking evening walks along the nearby limestone cliffs to “clear the lactic acid from my muscles and cobwebs from my mind.”

In 2014, when attempting this same dive — to a depth of 335 feet, he had blacked out from insufficient oxygen just below the surface. A flurry of safety divers had pulled him, pale and blue, from the water, as spectators and sponsors looked on and a camera crew from New Zealand broadcast the event on live television.

This time, having publicly declared that “I owe New Zealand a world record,” he struggled to push the tension from his mind. With his hands and feet resting on flotation devices, Trubridge closed his eyes, packing air into his lungs with a series of determined gulps. His goal was to relax into what he calls a “pre-sleep meditative state.” At the announcer’s signal, he turned to the water and pulled himself downward with an elegant breaststroke. He used no fins and no breathing equipment of any kind.

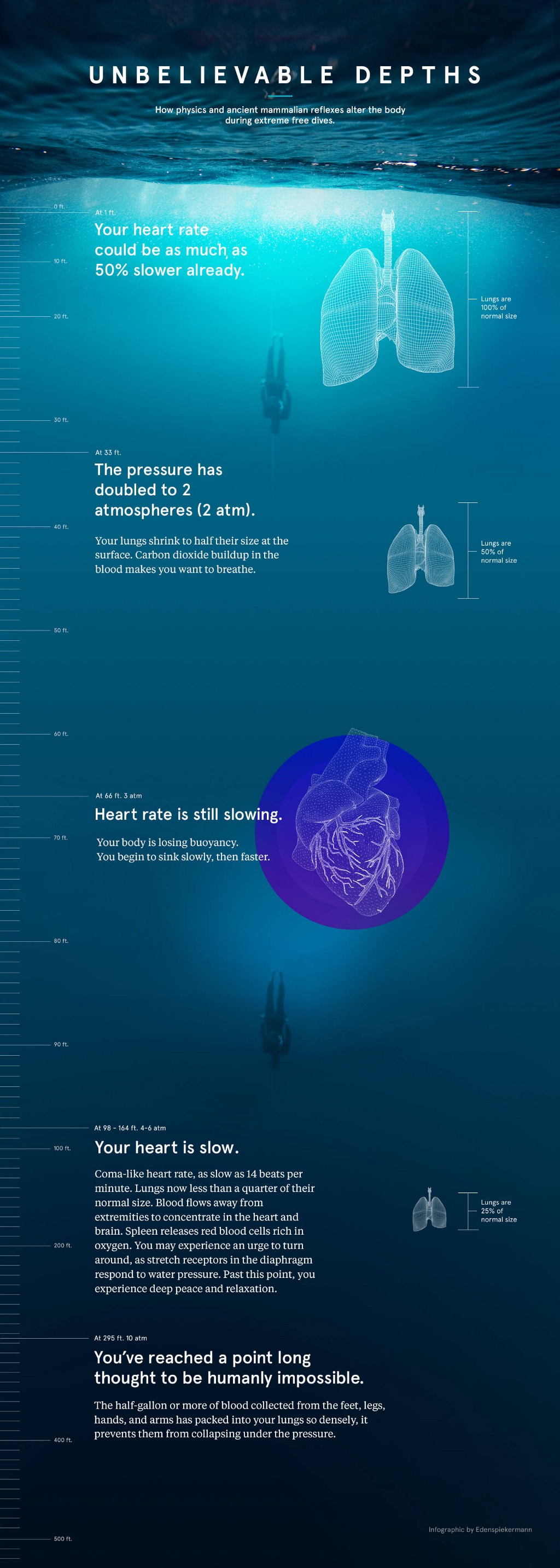

Underwater, amid particles of suspended sand and flashes of silvery fish, his heart rate slowed even as he swam downward with determined strokes. At a depth of around 66 feet, the air in his lungs had compressed so much that the sea no longer buoyed him up. He rested his arms at his sides and entered freefall, sinking placidly into the darkening water column.

As the pressure on his body mounted, he focused on emptying his mind. “There’s a subtraction of the stimuli around you, there’s no sound, very little light,” he says. “The water itself takes your thoughts away, it dissolves them.”

“William is the one they all want to emulate.”

After about two minutes, he reached a platform submerged at 334.7 feet and grasped a Velcro tag. “Touchdown,” said an announcer.

Then Trubridge turned into the hardest part of the dive, the grueling ascent. With long, slow strokes, he pulled against the weight of the water. In a kind of fugue state, for more than a minute, he swam upward through the water. Bathed in a glow of blue light, safety divers with undulating fins slipped down to guide him through the last third of his ascent.

This time, he remained conscious, gasping for air as he reached the surface and breaking the world record that he himself had set five and a half years earlier. As the crowd cheered, he beamed with elation and profound relief.

The dive represented Trubridge’s 18th world record and cemented his stature as the most accomplished free diver in the world. “William is the one they all want to emulate,” says Carla Hanson, president of the International Association for the Development of Apnea, a major organization supporting free diving. (Apnea simply means breath holding.)

At 36, Trubridge is strong and lean. But his physique — with normal-sized arms, hands, legs and feet — does not exactly scream super-elite athlete. Nor does his physiology, which is characterized by lung volumes and red blood cell concentrations at the high end of the normal range. For years, he has followed a strict regimen of stretching and strengthening exercises as well as yoga and meditation. He is preternaturally calm, focused and detached. “The mental discipline is his main advantage,” Hanson says.

Still, Trubridge wonders what other advantages might lie hidden in his body. Recently, he agreed to have his whole genome sequenced as part of an ongoing project of self-investigation. Now that he has dived deeper — on one breath, with no mechanical aid — than any human being has done before, how is he to understand his ultimate capabilities? How might the genome’s hidden indicia shed light on his limits? The answers, which we’ll reveal in Part 2 of this series next week, turn out to be far less straightforward than Trubridge or his genome-screening collaborators had expected.

For thousands of years, free divers have plumbed the depths in search of sponges, pearls, fish and shipwrecked treasure. In the waters around Korea and Japan, women known as the Ama foraged for food, diving dozens of times per hour, to depths of up to 80 feet in waters as cold as 50 degrees Fahrenheit. As early as the 1960s, scientists studying the Ama concluded that their baseline physiologies did not differ from those of other local women. Rather, their ability to hold their breath for minutes at a time, foraging at depth and returning successfully to the surface time and again, stemmed largely from training. They benefitted, too, from a response called the mammalian dive reflex: when humans hold their breath underwater (or even simply submerge their faces in cold water), their heart rate decreases to conserve oxygen. Blood vessels in their extremities also constrict, shunting blood to the heart, brain and other vital organs. The spleen, which holds a reservoir of oxygen-rich red blood cells, releases them into circulation, forestalling the need to breathe. (Researchers have studied people with and without spleens and shown that those who’ve had the organ surgically removed (for medical reasons) are not able to hold their breath for as long when submerged in a pool.)

Humans obviously can’t compete with aquatic mammals when it comes to breath-holding. (Weddell seals, for example, can stay submerged for an hour.) But the urge to challenge human limits has given rise to free diving as competitive sport. Athletes like Jacques Mayol and Enzo Maiorca, whose rivalry was memorialized in the 1988 cult classic movie The Big Blue, set world records in the 1960s, 1970s and beyond. In 1992, seeking to standardize rules and safety guidelines, a group of divers founded the International Association for the Development of Apnea. Today, the organization oversees training courses and competitions, promoting the view that free diving is not a “dangerous sport for thrill seekers,” but a “fantastic blend of inner peace, concentration, technique [and] training,” as its website puts it. The understanding that we all possess a diving reflex, written into our DNA, has also helped to democratize the sport.

At the same time, elite free divers devote themselves to reaching extreme depths, and this can take a toll. As Bill Strömberg, a former head of the diving association, puts it: “It’s about how well you know your body, and you don’t get that for free.” The deeper the dive, the more intense the pressure becomes; at depth, gases in the lungs become so highly compressed, the lungs themselves shrink to the size of apples. Oxygen throughout the body becomes more concentrated, which can trick the brain into thinking it is less scarce than it is. But when the diver turns around and ascends, the pressure falls and the lungs expand, causing the oxygen concentration within them to decrease. As a result the brain experiences an oxygen shortage, which can result in blackouts.

Free divers typically design their own training programs. For Trubridge, this has meant approaching diving “like a science project.”

Extreme pressure can also force blood into the delicate air sacs of the lungs, causing what’s known as a lung squeeze. For years, free divers tended to downplay the danger of these squeezes, which can damage lung tissue; even when the divers surfaced and coughed up blood, they often dove again during the same competition, rather than giving their bodies time to recover. In 2013, at an elite competition, called Vertical Blue, sponsored by Trubridge in the Bahamas, the American diver Nick Mevoli strove to break a world record for depth, despite a series of lung squeezes.

The dive was problematic from almost from the start. During his descent, Mevoli appeared to pause, then continue; at depth, his body jerked clumsily as he turned around. And on the ascent, he proceeded slowly. Though initially conscious at the surface, he failed to take in air, and after more than a minute he passed out. “He can’t breathe because he’s full of blood,” shouted one of the other divers. “His lungs are full of blood.” Despite efforts to revive him, he never regained consciousness. (Although athletes had been known to die while training alone, no fatalities had previously occurred during an official competition.) Post-mortem examination showed extensive scarring of Mevoli’s lungs as well as an enlargement of the heart, which likely resulted from the strain of diving with compromised lungs. “Numbers infected my head like a virus, and the need to achieve became an obsession,” Mevoli had written in a blog post two months before his last dive. “Obsessions can kill.”

Trubridge seems determined to steer far away from this trap, aiming instead for self-possessed balance. “The passion for me is just the beauty of the sport, the sensation of peace and quiet and otherworldliness of being underwater,” he tells me. It’s hard not to see this idealism as part of his familial inheritance. When he was a young child, his parents left England, where he was born, to live on a boat and travel, in part because they could not abide the conservative government of prime minister Margaret Thatcher. The family stopped occasionally on islands, where William’s father built furniture for wealthy expatriates, but he and his older brother grew up largely on the water, swimming, diving and spearfishing from an early age. The family eventually settled in New Zealand, where Trubridge attended school. For a time, he considered swimming competitively but realized he “spent too much time underwater, enjoying the glide phase,” which probably slowed him down.

Trubridge was also drawn to science, particularly genetics, which he studied as an undergraduate. In his early twenties, he led a sequencing team at a company called Genesis, studying the DNA of pine trees, cattle and sheep. But he missed the freedom of life outdoors and on the water. And when a friend introduced him to freediving, in 2002, he embraced it wholeheartedly. In 2004, he entered his first free diving competition, in Egypt, eventually moving to the Bahamas, where he could train at Dean’s Blue Hole and live a quiet, free-spirited life.

Since free diving is a small sport, athletes typically design their own training programs, with less input from coaches than in other competitive pursuits. For Trubridge, this has meant approaching diving “almost like a science project,” he says. Over the years, he has broken one depth record after another, while refining a personal regimen that involves stretching his chest muscles, strengthening his core and driving distraction from his mind. In one exercise, he undulates the muscles around his diaphragm and tucks them under his rib cage. He also practices exerting himself while holding his breath and avoids exercises that might build extra muscle mass, since muscles consume oxygen. In addition, he has adopted a largely vegetarian diet, favoring the bean sprouts he grows in his kitchen and the fish he catches himself with a spear. To boost his red blood cell capacity he takes iron supplements — free divers call it iron loading. In his case, it’s one to two capsules per day of a supplement called Proferrin Forte, made with Heme Iron Polypeptide (HIP), derived from bovine red blood cells, and folic acid. He also receives 100-milliliter injections of vitamin B-12 bi-weekly, depending on availability on the island.

Considering all the elements that are required to dive successfully — from breath holding to flexibility to meditative skill — he argues that “the most important quality for any free diver will always be dedication,” rather than innate ability.

Still, after 18 world records, Trubridge has grown curious about his own inborn propensities. Enter Rodrigo Martinez and Veritas Genetics. Martinez is the chief marketing and design officer of Veritas, the first company to offer whole genome sequencing to consumers for $999. Martinez happens to be a budding free diver, so he approached Trubridge on Facebook and asked if he would like to have all 6.4 billion letters of his genome sequenced. This approach offers a more comprehensive picture than an alternate method, called genotyping, that is also commercially available and that provides individuals with information on the specific DNA variants they possess in selected parts of their genomes. Being a former geneticist, Trubridge readily agreed, wondering whether it might reveal a subtle advantage in his ability to absorb iron or transport oxygen or hold his breath. “I have no expectation about what it will be,” he tells me. “It’ll be interesting to find out.”

What he learned was more troubling than he ever anticipated.

Part 2 of this series:

The Genetic Secrets of the World’s Greatest Free Diver