William Trubridge’s genome reveals some of his superpowers — and why his training is riskier than he ever imagined. Part two of a three-part series.

You can read part one of this series here and part three here.

In the mid-1990s, an academically gifted Bosnian teenager named Mirza Cifric sent a plea to thousands of people through an online bulletin board system. The Bosnian War had come to an end, but Cifric, already a serial entrepreneur since middle school, saw little future in his homeland and wanted to pursue a college education elsewhere. Strangers from around the world responded to him, and eventually, through an organization devoted to helping Bosnian children, he was matched with a family living outside of Boston. Cifric says he printed the invitation on his Star LC20 dot matrix printer and ran to his mother, waving the paper and shouting, “Mom, Mom, I’m going to America!”

Happily, Cifric was picked up at the airport by his American host family and went on to study electrical engineering at Northeastern University. Today, he is the CEO of Veritas Genetics, which provides DNA sequencing and interpretation for researchers, physicians and consumers. “I’m compelled to do something meaningful, knowing I got the opportunity to come here” while so many other people didn’t, he says.

At Veritas’s headquarters in Danvers, Massachusetts, the still boyish Cifric offers an enthusiastic tour of the laboratory facilities — from the room in which customers’ blood or spit samples are logged and barcoded, to the space in which DNA is extracted from cells by robots, to the area in which Illumina HiSeq X sequencing machines provide raw data on the six billion letters of DNA making up an individual’s genome. When the machines are running, an intricate pattern of fluorescence allows the letters to be identified. “You almost see like a constellation of stars,” Cifric says with childlike appreciation.

Since 2001, when the Human Genome Project first cracked the basic code for our species, over 500,000 whole human genomes have been read. The first belonged to scientist Craig Venter, who funded his own effort, publishing his whole genome in 2007. Others, drawn largely from the ranks of biomedical researchers and the tech-savvy, soon followed, motivated to aid science as well as to learn about their own genetic makeups.

Cifric believes, however, that the field is now at an intellectual and commercial tipping point. He argues that scientists possess a critical mass of information — on how gene variants correlate with traits like drug sensitivity and athleticism or influence people’s risk of cancer, diabetes, and heart disease. Much of this information is “actionable,” he says, meaning that it can lead to targeted changes in diet or lifestyle — or further screening — to protect individuals’ health.

In 2016, Veritas became the first company to offer whole-genome sequencing for $999. This price point had been considered a holy grail by those promoting broader access to genomic information, who speculated that it represented a threshold beneath which demand would increase substantially. Unlike direct-to-consumer companies such as 23andme and Ancestry.com, Veritas requires patients to have a physician’s referral, which allows the company to provide more medical information. And while 23andme and Ancestry.com offer genotyping, which reveals the DNA variants that consumers have in selected parts of their genomes, Veritas and other groups that offer whole genome sequencing reveal a more comprehensive set of personal data. That includes all 3.2 billion base pairs of their DNA, which can be analyzed today but also queried again down the road. Indeed, as more and more genetic markers are discovered, the value of having a whole-genome scan may continue to increase.

By charging so little for the analysis, the company makes “little or no money,” Cifric says. The goal is to woo customers in hopes that some might pay more for extra counseling or further analysis at some point in the future. The company also offers targeted genetic tests, like those for the BRCA mutations that predispose women to breast cancer, and plans to introduce sequencing of the microbiome (the vast ecosystem of bacteria in your body) in 2017. In the process, the company is also building a repository of genomes to be used for research.

Cifric believes that genome sequencing is now at an intellectual and commercial tipping point.

In recent months, Veritas’s machines have lit up with the DNA of hundreds of people — including, notably, the preeminent free diver on the planet, William Trubridge. A 36-year-old New Zealander who has amassed 18 world records, Trubridge can dive to depths of more than 330 feet into the ocean on a single breath — with no fins or gear. Thanks to a strict regimen of meditation, strengthening, and stretching, he moves through water with the grace of a porpoise, even as the water pressure around him grows crushing, collapsing his lungs to the size of apples. Free diving lacks standardized training techniques, “so you need to be a researcher yourself to find what works,” he tells me. “It seems to attract scientific minds.” (Not unlike genome sequencing.)

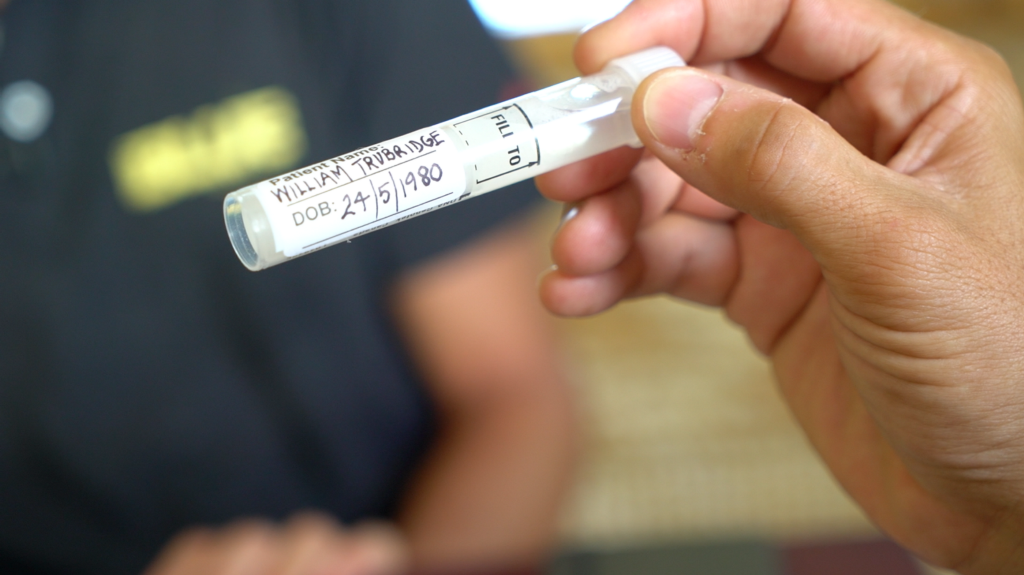

Last year, Veritas’s chief marketing and design officer, having already arranged for the company to sequence the DNA of astronaut Scott Parazynski, offered to analyze Trubridge’s genome for free. Trubridge was intrigued enough to submit a vial of saliva for testing. In particular, Trubridge wondered whether his DNA might shed new light on his athleticism — or suggest ways to hone his training. He studied genetics in college and worked, years ago, sequencing agricultural and horticultural samples in New Zealand, when far less was known about the DNA underlying human traits. Like free diving, he says, genetics is filled with interesting, “fledgling ideas.”

In early January, Trubridge is at his parents’ house on the Mahia Peninsula in New Zealand for the holidays, when the Veritas team opens up a video call to share its results. Normally, patients discuss their reports confidentially with a genetic counselor, but because Trubridge has agreed to share his results publicly — and because of his celebrity — several team members pull up chairs and huddle around the computer screen, including the company’s head genetic counselor, Sharon Namaroff.

The company’s chief scientific officer, Preston Estep III, dressed casually in a black fleece and gray baseball cap, leads the discussion on athletic performance. The results are as clear as paint. Flipping through pages of results, Estep wonders aloud at a finding related to lactate, a substance that accumulates in muscles when they lack sufficient oxygen, causing a burning sensation. He expected Trubridge might have a lower tendency to produce lactate compared to other athletes, since he excels at diving on low oxygen. “But it’s the opposite,” he says with a tiny shrug. According to the report, Trubridge has, if anything, a predisposition toward higher blood lactate and less responsiveness to training. Trubridge looks quizzical. “In conversation with other free divers, it seems like I become less lactic than most,” he says. “It would surprise me if I had a higher baseline level.”

Estep also grapples with findings that might relate to Trubridge’s aerobic capacity. Athletes like runners and cyclists try to boost the maximum amount of oxygen that their muscles use per minute, a metric known as VO2 max. As a free diver, however, Trubridge does not want his muscles to consume large amounts of oxygen while deep underwater. (“My training has avoided cardiovascular exercise,” he says.) Even so, according to the report, Trubridge has one genetic variant associated with a lower-than-normal VO2 max, one associated with average VO2 max, and one associated with higher VO2 max. I “wouldn’t be surprised if overall you had a higher VO2 max,” Estep says. Trubridge listens politely.

He is lean and strong; in videos that show him underwater, ascending from deep dives, he pulls with long, efficient strokes, gliding for long moments in between. His power is remarkable in part because his body has so little muscle mass — nothing like the bulk associated, say, with elite swimmers. This, again, is partly by design, since muscle consumes oxygen, which Trubridge works assiduously to conserve. So, he is intrigued when Estep flags two other genetic variants in the report: one that is linked with lower muscle mass and one that is associated with higher muscular power. That genetic predisposition rings true to him: “That’s good for my power-to-weight ratio,” he says attentively, smiling.

Still, the link between Trubridge’s genome and his achievements remains murky, at best. In part, this reflects how little is known, so far, about genetic variants that relate to athletic ability. “The exercise community is where the disease community was 10 years ago,” says Euan Ashley, a professor at Stanford University Medical Center who studies exercise and genetics. A smattering of small studies suggest links between specific variants and athletic traits. But those links may or may not bear out in larger-scale work, and even if they do, they may not predict large differences in ability. Most of the research cited by Veritas on specific genetic variants and athletic traits, like muscle mass, represents early-stage work, Ashley says: “For any of these claims to be believable, you’d want to see at least two studies in at least two independent populations usually with at least 1,000 people.”

Trubridge’s genome has variants linked with lower muscle mass and higher muscular power.

By contrast, when it comes to Trubridge’s health risks, the report reveals a set of genetic variants with well-established and potentially serious implications. Trubridge carries a mutation in a gene called BRIP1, which is associated with an increased risk of cancer, particularly in women. If Trubridge inherited this variant from his mother (as opposed to his father), her risk of breast and ovarian cancer would be significantly higher than the population average. Trubridge promises to discuss this with his Mum, who is 67 years old and in good health. The report also includes a few mutations that could be relevant for any children he might father, if his partner carries the same variants he does. That’s because the diseases are autosomal recessive, meaning that individuals must inherit two copies to be affected. These conditions include homocystinuria — a rare metabolic disorder — and complement component deficiency 9, which affects the immune system and can lead to chronic infections. Trubridge takes the news in stride. For the time being, the possibility of becoming a father is theoretical; after years of marriage to an American yoga instructor, whose father was one of his safety divers, he is now divorced.

The most dramatic finding in the report, however, involves Trubridge’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease; it suggests an eventual collision between his diving career and his health. Trubridge carries a variant known as APOE e4, which means he is two to three times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease late in life. Individuals with two copies of the variant are more than 10 times likelier to develop the disease than those without the risk factor. (Approximately 17 percent of men and 9 percent of women overall develop Alzheimer’s disease by age 65.)

Estep does not usually counsel patients, nor is he a physician. (And as he launches into a blunt presentation of Alzheimer risk, in the midst of a crowded room, Namaroff, the genetic counselor, looks uncomfortable.) As a scientist, though, Estep has explored how dietary factors interact with our genes and influence our health — especially the health of our brains. In fact, he has taken particular notice of the potential effects of dietary iron intake on brain health. In his 2016 book The Mindspan Diet, he argues that when it comes to Alzheimer’s disease, elevated intake of iron is a particular risk factor. Increased concentrations of this metal in the brain are associated with the progression of disease. And for people who carry APOE e4 and are already at heightened risk, high iron may be especially toxic. “That might not sound like a good thing,” Estep tells Trubridge. “But it actually is because it gives you some control.” A diet low in iron, in other words, might mitigate the risk associated with e4.

But here’s the catch: for Trubridge to succeed at the highest levels of free diving, he needs to do everything possible to boost his oxygen-carrying capabilities. “I need to supplement with iron,” he says quietly, and the quantities he ingests are not small. His iron-loading regimen involves ingesting a daily dose of 12–24 milligrams of heme iron, derived from bovine red blood cells.

As a 36-year-old, Trubridge’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease in the next decade or so is extremely low, Estep reassures him. But “you are going to have to make a decision at some point in life to trade athletic performance for reducing your risk.”

Figuring out how to strike that balance leads to a thicket of bewildering questions. For instance, if he stops competing as a free diver in the next five or seven or eight years and stops supplementing with iron — and maintains a vegetarian diet — will he have managed not to exacerbate his Alzheimer’s risk unduly?

Hard to say. Not all scientists agree that dietary iron is a risk for Alzheimer’s disease progression. In most people, iron does not easily cross the blood-brain barrier, according to Peng Lei, a translational neuroscientist at Sichuan University in China. Still, diving may further complicate the picture for Trubridge, since he trains regularly under conditions of low oxygen — and low oxygen itself seems to stimulate iron transport into the brain.

In addition, once iron has built up in the body — and especially in the brain — it is not easily removed. This means that the longer Trubridge continues diving and supplementing, the more he reaches for new depth records and strives for immortality in his sport, the harder it will be later to lower the risks to his brain.

At the same time, precise risks are difficult to calibrate. Indeed, while Veritas has made good on its promise of “actionable” information, it has also thrust Trubridge into a newly uncertain realm in which he has some cause for concern but can’t draw straight lines from the choices he makes today to the probability of later disease. Nor is this conundrum unusual for those receiving genetic information; the data can sometimes lead to less clarity, rather than more — requiring recipients to deal with uncertainty around a set of variables that they hadn’t even previously considered.

Trubridge is accustomed to taking risks for sport, much as football players set themselves up for concussion. And like many competitive athletes he has a fervent belief in the strength and health of his body. His signature traits — in life as well as in the water — are single-mindedness and an apparently unshakeable equanimity.

When Trubridge prepares for a dive, he focuses on remaining “exclusively in the present moment,” he has written. “It’s so easy for your stream of conscious thought to float you into a swamp of speculation about what may or may not happen in the future.”

Before his record-breaking dive to 335 feet last year, he conditioned himself to think less about eventualities. He repeated the mantra, “now is all.” And any time his thoughts slipped nervously toward the future, he reminded himself that “the only moment that is ever happening is the now.”

That discipline is Trubridge’s greatest gift as a diver; but it may also be a deficit when it comes to making sense of a genetic liability. (His utter calm seems almost to unnerve Namaroff, the genetic counselor.) Ultimately, he says he will do some reading on the science of Alzheimer’s. Then, he returns to his New Zealand vacation, disappearing from the screen and leaving the Veritas group to wonder at his thinking.

A month later, he will be ready to elaborate on his plans.

Loving this article? Check in with us next week for the conclusion to our story. And please share this link with any friends you know who would appreciate proto.life!

More information about Veritas Genetics can be found at the company’s website.