Facing troubling news in his DNA, William Trubridge displays a competitive advantage not found in his genome: equanimity

Part three of a three-part series. Read the first two parts of this series here and here.

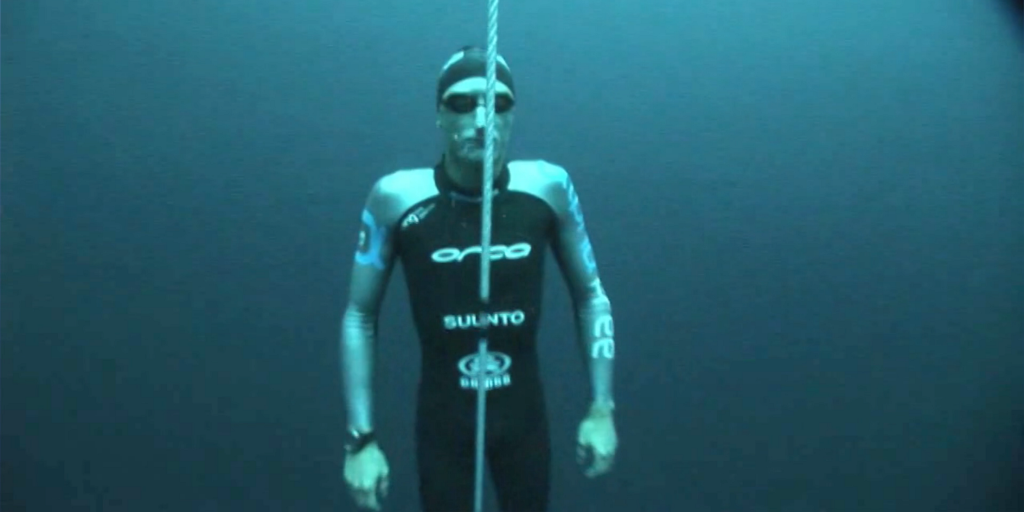

Competitive free diving — in which athletes descend to crushing depths on a single breath and frequently lose consciousness on the way back up — hardly seems like a pastime for late middle age, like tennis. It has been described as “the world’s second-most dangerous activity, after jumping off skyscrapers with parachutes.”

Yet older athletes have accomplished some of its signal achievements. In the 1970s, the French diver Jacques Mayol, whose life inspired the cult classic film The Big Blue, set a world record, reaching a depth of 330 feet in a “no limits” dive, in which athletes are permitted to use weighted sleds to hasten their descent. He was 49 years old at the time. In the 1980s, he bested this feat by descending to 344 feet — at the age of 56. More recently, the legendary Russian diver Natalia Molchanova broke a world record at the age of 53.

This may be, in part, because free diving depends so heavily on mental fortitude. The best divers can clear their minds of tension, distraction, and even conscious thought as they descend. William Trubridge, a New Zealander who has broken 18 world records, has adopted a series of mantras when underwater, including “shut down, shut down …” and “now is all, now is all…” Older divers are more mature, he says, “more mentally equipped to deal with stress and performance anxiety.” Individuals’ metabolisms may also slow with age, making it easier to conserve oxygen.

Trubridge, who is 36, plans to dive for the rest of his life, at least as an amateur. But the question of how long he’ll persist as an elite competitive athlete recently surfaced when he decided to have his genome sequenced. In January, he learned that he carries a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease known as APOE e4. Because Alzheimer’s progression is correlated with higher concentrations of iron in the brain, the scientists at Veritas Genetics who provided his results advised that over time he ought to slash his iron intake.

This advice seems to collide, however, with Trubridge’s long-term athletic prospects. To excel at the highest levels, he must maximize his blood’s oxygen-carrying capacity, in part by supplementing aggressively with iron — divers call it iron loading. In other words, to maintain his preeminence, he is dosing his blood and brain with the one nutrient most likely to cause him long-term, cognitive harm. (“It’s pretty clear what the actions are to take,” says Preston Estep III, the chief science officer of Veritas who presented Trubridge with his results.)

Yet Trubridge has responded to the news with remarkable serenity, displaying the very trait that has made him so successful as a diver: his skill at absorbing conflict and tension and dissolving them away. The first time he took an iron supplement after receiving his genomic results, “it took on an extra significance for sure, but it didn’t make me hesitate or sway my habits,” he says. “It’s not something that hit me hard or freaked me out at all.”

Scientists are only beginning to explore the complex underpinnings of resilience.

The chances that Trubridge will develop Alzheimer’s disease in the next 10 years are low, according to the scientists at Veritas. And so, he reasons, if he ends his competitive career in his 40s — and no longer supplements with iron — he can mitigate his risk to a reasonable degree. “In terms of competing and pushing myself so aggressively, I think that’s untenable past some point in my 40s,” he says. (Whether that represents a bit of rationalization — combined with mental fortitude — is hard to say.)

Trubridge’s genomic report did not include any analysis of his psychological traits, such as his variant (or variants) of a gene called COMT, which appears to help determine whether someone has “warrior” or “worrier” tendencies. So the compelling question of why he and other elite free divers can rid themselves of tension so successfully remains unanswered. Natalia Molchanova often spoke about a Russian technique known as attention deconcentration. “You focus on the edges, not the center of things, as if you were looking at a screen,” she told a New Yorker reporter. “Basically, all the time I am diving, I have an empty consciousness. I have a kind of melody going through my mind that keeps me going, but otherwise I am completely not in my mind.”

Trubridge, too, has spoken about the melody of church bells, which he sometimes sings to himself very slowly. He does this so that his “heart and everything falls into the very slow rhythm and everything slows down,” pushing away the negative thoughts, like “’you’re gonna die down here.’” (Molchanova did die, in 2015, while free diving off the coast of Spain.)

Kerry Hollowell, a free diver and the medical officer of the diving organization AIDA, speculates that free divers have an unusual ability to “let go completely, trusting in their bodies and letting go of their minds, surrendering to the water.” Free divers’ training puts an enormous emphasis on meditation and breathing techniques. For some, these practices may strengthen a predisposition toward resilience, mental discipline, and calm. At the same time, these breathing techniques might also teach people who are prone to anxiety not to panic, says Hollowell, who is an emergency room physician. Diving has helped her not to “freak out when someone is dying in front of me.”

In recent years, scientists have begun to explore the complex underpinnings of resilience. These include the genetic, molecular, neural, and hormonal mechanisms that seem to go hand in hand with the ability to manage stress without succumbing to psychiatric illness. A growing consensus suggests that “resilience in humans represents an active, adaptive process, and not simply the absence of pathological responses that occur in susceptible individuals,” according to Eric Nestler, director of the Friedman Brain Institute at Mount Sinai in New York.

The ethos of freediving would seem to support these findings. As would Trubridge’s response to his APOE e4 results, which seem to have dissipated in his mind like a stream of bubbles. Indeed, whatever the conflict that others might perceive between Trubridge’s genes and his ambitions, his own takeaway has been that “there wasn’t any major windfall or anything I had to wrap my head around so it was quite an easy thing.” Which is to say, Trubridge’s head game seems as freakish as his ability to collapse his lungs beneath his rib cage.

Diving is “like stepping into the realm of death,” he says. And the lesson it teaches — which he applies to life, as well — is that the diver must dissociate from the future, even when that feels like a “counter-instinctive thing to do.”

Sign up now for our newsletter at www.proto.life.