Nicole Prause left academia to study sexuality without institutional limits. Now she’s challenging orthodox views of climax and pornography.

Nicole Prause is packing up her lab — again. She relocates about once a year. This time, she’s moving because a public filing required her to disclose her business address. Better safe than sorry.

Prause is a neuroscientist and psychologist who studies sex, one of only a handful of scientists in the world trying to answer fundamental questions about what happens in our bodies and brains while we’re in amorous congress. After being pushed out of her job at UCLA in 2015 because the ethics board wouldn’t let her study orgasms in human subjects, she struck out on her own, founding an independent research company called Liberos.

She’s also a target for anti-pornography crusaders. They send her hate mail and death threats and do everything they can to shut down her research because she’s outspoken in her belief that they spread harmful lies by claiming porn is dangerous and addictive.

As a scientist, she’s curious about how we turn on and what happens when we do. As a target, she wants to get the word out that science is on her side.

Prause lately has stepped into an even deeper debate. What is an orgasm, anyway? How can we distinguish the physical manifestations from the psychological experience — especially in women, whose verbal reports may not match measurable physiological responses?

Her most recent findings not only shed light on sexual response, but also reveal just how much we have to learn about the experience at the center of our very survival as a species.

The measure of pleasure

A lanky woman with a relaxed, confident presence, Prause recently completed a study in which she observed the orgasms of 21 women between ages 20 and 46. The work was funded by a vibrator company that wanted a scientific assessment of its product (there are currently no industry standards or methods for evaluating sex toys). But the contract gave Prause control over the study design and ownership of the data. So she set out to see how the women’s orgasms differed between using their hands versus the vibrator, and to see whether their consumption of pornography affected the quality of their orgasms without it.

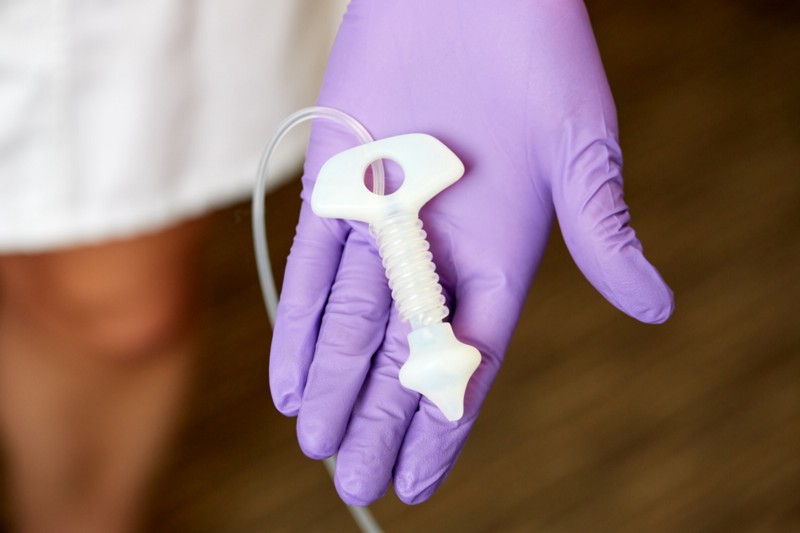

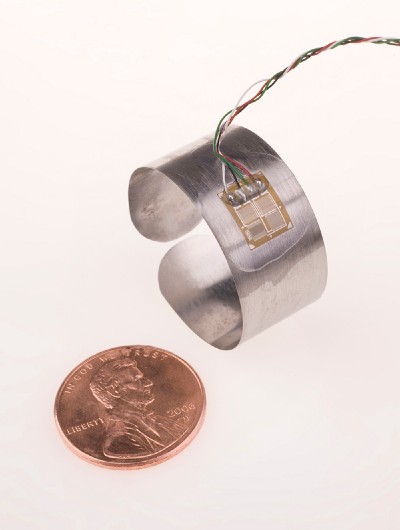

The subjects came into the lab twice. Each time they positioned themselves on a medical table and were fitted with a series of monitoring devices: electrodes on the scalp to measure brain waves, galvanic response monitors on the soles of their feet, and a new “anal probe” — a sly phrase she chose for its association with alien abduction fantasies — that she developed to measure contractions during orgasm. Wires ran from the subject to the small office next door, where Prause monitored the signals.

During one visit, subjects masturbated with the vibrator, during the other with their hands. In each case, they pushed a button to signal the beginning and the end of orgasm — subjects climaxed in all but 2 of the 42 attempts — and afterward filled out a questionnaire describing the sensations they had experienced.

The answer to the hand-versus-vibe question was unsurprising: The device brought on longer, more intense orgasms. Chalk one up for the Lovehoney Happy Rabbit.

“I would never dare tell somebody they’re not having an orgasm just because there were not rectal contractions.”

But Prause’s finding with respect to the impact of pornography on the quality of orgasm may surprise some people. The women who reported the heaviest porn use also experienced the longest and most intense sensations. Their habitual consumption of erotic imagery didn’t diminish their pleasure, even when it wasn’t available. Their porn habit even may have enhanced their pleasure.

Many people opposed to pornography believe that such erotica — and sex itself — can be addictive. Prause thinks this is misguided for several reasons. Mainly, people who report distress due to their porn use don’t fit the typical model of addiction. If porn were addictive, scientists would expect to see signs of withdrawal when it’s not available, for example in Prause’s subjects who had watched a lot of porn and then masturbated without it.

“If the addiction model is true, we would expect worse orgasm in this study for heavy porn viewers,” Prause says. That she didn’t observe such an effect in her (admittedly small) study gives her new ammo in her battle with the anti-porn crowd, and she says there’s no reason to think men would function any differently.

Sexual healing

Prause isn’t pursuing this crusade for pornography’s sake. She’s establishing a scientific basis that therapists might use to help people suffering from sexual issues of all kinds. “It’s about, how do you help people when they walk in your door and say, ‘I’m really upset about my porn viewing?’” she says.

Prause believes that most people who watch a lot of porn simply have a higher sex drive, not a true addiction, which would entail experiencing not only withdrawal but also the need for ever-greater stimulation such as increasingly extreme material. She says the main factor in whether people are distressed by their pornography or masturbation habits isn’t how much they indulge — it’s whether they had a conservative religious upbringing.

It’s important to understand whether addiction, high sex drive, or shame is upsetting patients, because “the interventions are night and day” depending on where the problem lies. “So if you get the wrong model, [therapists] can really fleece patients,” she says. Being labeled a sex or porn addict means therapy for a disorder that may not really exist. Furthermore, it means a disease label attached to your insurance, as well as likely being told by a therapist that you’re “always in recovery.”

And Prause saw something interesting in the results from her anal probe. About half of the subjects reported orgasms while they weren’t actually climaxing, according to measurements of their anal contractions.

She doesn’t think they were faking it. Subjects were clearly told they would be paid either way, and that not having an orgasm also would yield important data. It’s more likely, she says, that they identified their experience as orgasmic because they didn’t know what a true orgasm — with strong pelvic floor contractions — feels like.

“Maybe they don’t know what it feels like, because they maybe don’t know to expect it, aren’t even looking for it,” she says.

What is an orgasm, anyway?

Not all researchers agree with Prause’s definition of female orgasm, highlighting the fact that basic questions about sex remain unanswered.

“She has a really good track record of getting stuff done,” says Nan Wise, a cognitive neuroscientist and sex therapist who conducted research on orgasm as part of her PhD at Rutgers University. But “I would never dare tell somebody they’re not having an orgasm just because there were not rectal contractions.” An orgasm is both a physical response and a “massive brain experience,” she says.

“I’m a big fan of thinking of orgasmic experiences as a range of experiences that have at its core some really strong bump up of intense pleasure, with associated physiological measures that may be very variable,” Wise says.

But Prause envisions a future when doctors recommend orgasm to help with problems like insomnia or chronic pain. For that to work, they’ll need to agree on what an orgasm is.

Mismatched sexual desire is the most common problem among couples seeking help with their sex life.

Research into the granular details of orgasm and the effects of porn could also illuminate broad societal problems, such as a phenomenon The Atlantic explored in a recent article called “The Sex Recession.” The article surveyed possible reasons why young adults and teenagers are having significantly less sex than previous generations.

On this issue, Prause is decidedly optimistic. She thinks we may be seeing the quality of sex increasing even if the frequency is decreasing.

“Behaviors have broadened a lot,” she says. She points to the fact that there’s more oral sex and other non-traditional intercourse among couples, and that many people are more comfortable turning down sexual activity they don’t want but might in the past have felt obligated to take part in.

Even the facts that porn, vibrator use, and masturbation are increasing is a good thing, she says. Mismatched sexual desire is the most common problem among couples seeking help with their sex life, so “a masturbation increase doesn’t mean someone is less connected to other humans,” she says. It could mean they’re doing something that reduces tension in their relationships, perhaps leading to a more harmonious sex life.

“Maybe instead of a sex recession, we should call it a sex flourishing,” she says — whether or not anyone has an orgasm.